43 Hasker Street, London

After his permanent move to Wales in June 1956, Russell continued to use his small flat at 29 Millbank SW3 until 1958 when it was torn down. Where the flat once stood is 30 Millbank Tower. The tower sits between the Tate Gallery and Thames House. With the demolition of Millbank, Russell lost his London base. He and Edith needed to maintain a presence in London for meetings and appointments as well as for seeing friends and for Russell to appear on BBC broadcasts.

Tate Gallery and Millbank Tower

He briefly considered returning to Richmond. He looked at “the purchase of a house on the Green at Richmond”, telling his lawyer Louis P. Tylor on 3 June 1958 that “I cannot afford to purchase unless I can get a mortgage for four or five thousand pounds &, so far, this remains in doubt.” This was not really a practical solution because even when he lived in Richmond he maintained a London base.

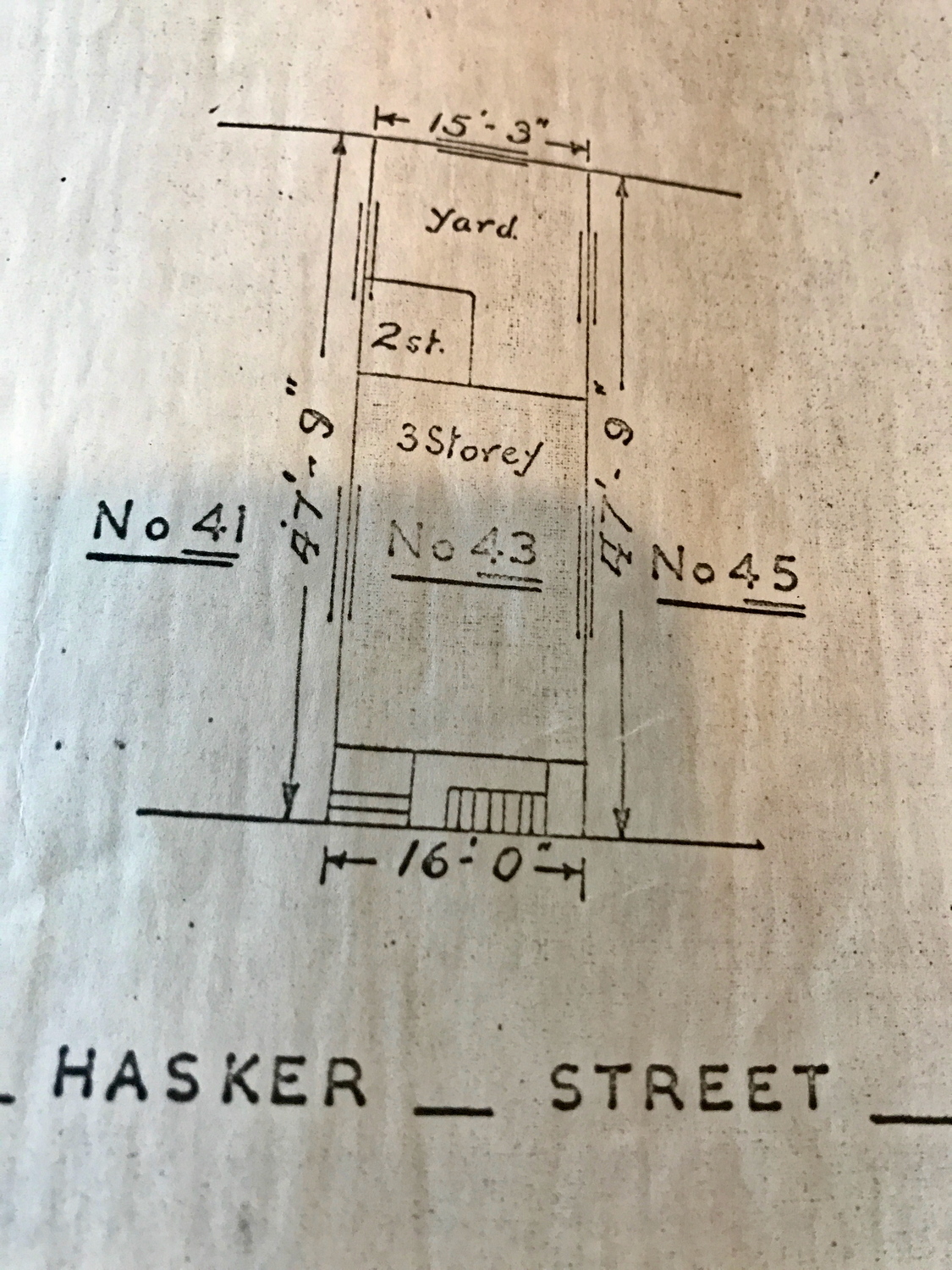

In the end, Russell and Edith acquired a townhouse at 43 Hasker Street, SW3. It was larger than the Millbank flat and better suited to more lengthy stays. Russell purchased the lease between Gerald Charles Earl Cadogan, Cadogan Settled Estates Co. and Flavia Dorothea Clarke on 27 October 1958; he paid her £3,300. Begun in 1955, it had 18 years left to run, expiring on 29 September 1973. There was a muddle with regard to negotiations and the agent Roy E. Brooks’s commission was in doubt. When Russell stepped in to assume payment if necessary, Brooks wrote on 12 September that he “was delighted to receive your letter as we so rarely find that the private business actions of a Great Man match up to his public reputation!”1Russell informed Harrods on 16 October that the house would come into his possession on 8 November and he would like his furniture moved shortly thereafter. Moving day occurred on 11 November.2The rent was only £5 a year. However, the responsibilities of a tenant were vastly different than what is expected in North America. Russell was required to paint the exterior in 1958 and every fourth year thereafter and to redecorate the interior in 1957 and every seventh year thereafter, and was responsible for all repairs.3Even more than ten years after the war had ended, there was a telephone shortage, so the Russells took over Mrs. Clarke’s telephone while the telephone in their Millbank flat went to their housekeeper Jean and her husband Cecil Redmond who lived nearby at 40 Oakley Street. It took six to eight months for a new telephone to be installed while transferring the Millbank one would take only six to eight weeks.4

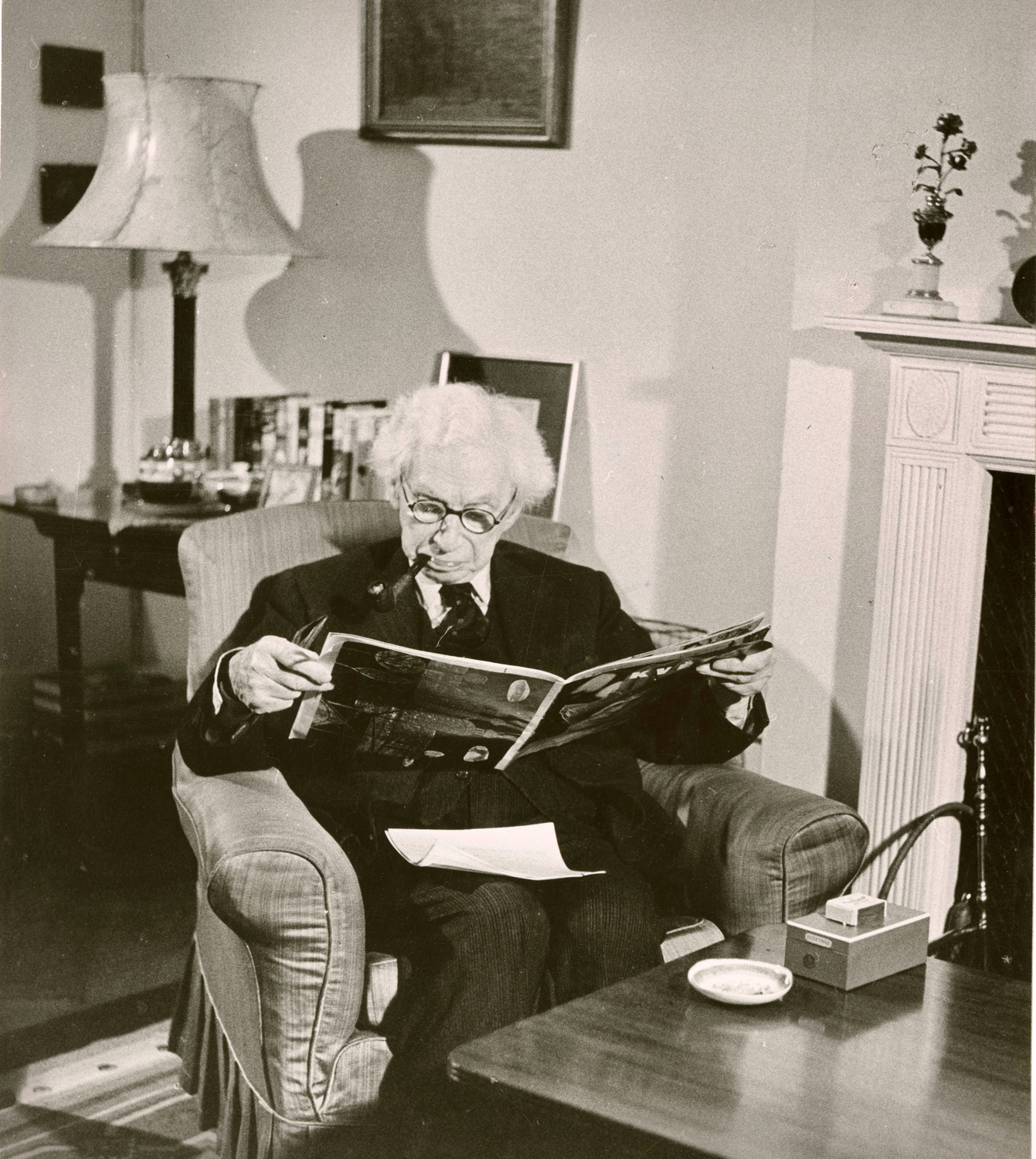

Russell and Edith

Hasker Street is in the same postal code, SW3, as Sydney Street where Russell lived with his second wife Dora in the 1920s. He described the location as “a little street running from Walton Street to Milner Street at the Knightsbridge end of Chelsea” to his doctor, J. Lister Boyd, on 17 November 1958. The three-storey townhouse was 16 ft. wide at the front. There was a two-storey attached outbuilding in the rear.5The Redmonds looked after the property. Jean had previously worked for them at their Millbank flat. A month after they occupied the townhouse Russell informed Chesterton & Sons, the estate agents in charge of his Millbank flat that he had left the keys to that flat with his housekeeper Jean who would be returning them.6It is possible that these keys were not returned. A group of keys used to illustrate the Home Page of this website has a tag attached labelled “flat keys”. Hasker Street was locked with an Ingersoll key. At first the Redmonds lived nearby but in 1961 had to move further away to SW6. The Russells helped them financially with this move. There is a large amount of correspondence between Edith and Jean regarding the running of the house. Cecil, though he had employment elsewhere, undertook small odd jobs. Major repairs such as a new slate roof in 1959 were done by outside contractors. When interior painting took place in December 1961 Edith’s request to the painters, S.J. Walker & Son, was for the walls to be “pure white in colour ... not … pinkish or yellowish or greyish” (18 Dec.). The house was heated with “smokeless fuel” which did in fact not provide any heat (King-Hele, p. 24).

Russell mentions Hasker Street twice in his Autobiography. The first concerns the formation of the Committee of 100 and his relationship with Canon Collins who is not named, but only given his title, the chairman of the CND. “During the first week of October [1960], I met with him daily for many hours at my house in Hasker Street to try to work out some modus vivendi” between the two organizations (Auto. 3: 111). There were two other unnamed participants in this marathon which ended in failure. The second mention concerns his release from Brixton Prison in 1961: “… we were besieged by the press and radio and TV people who swarmed into Hasker Street (Auto. 3: 117). Russell wrote 200 letters from Hasker Street beginning in 1958 and ending in June 1966.

In April 1959 Russell went to a television studio every day from Monday the 13th through Saturday the 18th. Edith in a letter to Jean Redmond, 6 April written from Wales noted the types of soft food that would have to be prepared. “It is the parlous state of the world that, I think has worried Lord Russell so that his throat does not work properly.” The interviewer was Woodrow Wyatt; the texts of the interviews were published as Bertrand Russell Speaks His Mind in 1960.

The house was a hub of activity. In 1960 Edith listed all the people they had to see during their visit to London. They included Augustus John, Joseph Rotblat and Patricia Lindop, Wolfgang Foges of Rathbone Books, Gogi Thompson and husband, the Trevelyans and the Themersons in addition to their doctor and many others (London Appointments, 4 Feb. to 3 March, document 311545). Vanessa Redgrave came for tea twice in 1961: 28 November and 3 December (“Friends and Visitors”, document 313300). In the spring of 1961 their planned visit to London had to be cancelled because Russell came down with shingles (Edith to Jean Redmond, 11 April 1961).

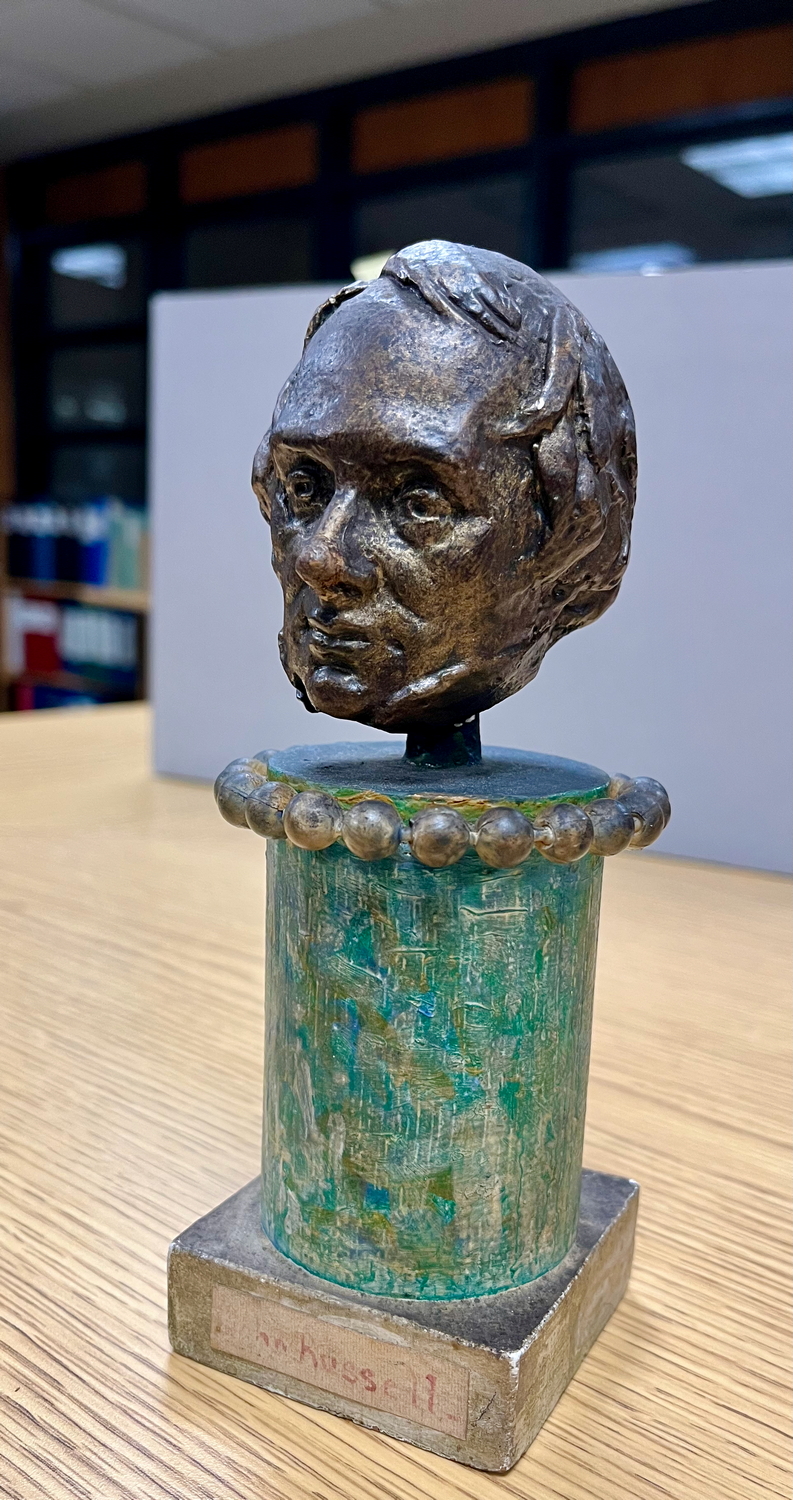

In May 1962 Russell celebrated his 90th birthday in grand style. On the 18th there was a dinner at the Café Royal. The next afternoon there was a celebration at the Royal Festival Hall with music and presentations. His cousin Flora Russell could not attend but she gifted Russell with a bust of Socrates (Auto 3: 123). Flora (1869-1967) was a granddaughter of Major-General Lord William Russell, Lord John Russell’s brother. On 27 May she wrote to Russell that she would like to visit him and be photographed with Socrates and also “a little head” of Lord John’s. The head had been given to her by her mother, Lady Laura Russell (née de Peyronnet) “by Alfred Gilbert when he took over the studio of the sculptor Boehm, who I think did the statute at Westminster.” Joseph Edgar Boehm (1834-1890) did create a sculpture of Lord John which is housed in Westminster Abbey, North West tower chapel. Russell replied on 29 May, thanking her for the Socrates: “I was gratified to think that you felt me a suitable companion for him … I like the idea of you and me and Socrates and my grandfather together in a photograph.” Flora visited him at Hasker Street on 6 September. On 24 September she sent Edith some photographs: “Some are rather good, but Socrates is apt to be a ghost.” The statue was white which is often difficult to photograph. In the same letter Flora wrote: “I have handed over the head of Uncle John to an expert about casting at the” British Museum. The casting was made and Flora delivered it to Russell at the end of October. It was taken to Plas Penrhyn and displayed on top of the revolving book case. It now resides in the Archives. The head shares the same wording as the bust in Westminster calling Lord John “John Earl Russell”.7

Russell with Flora

Lord John bust photographed in the Archives

In August 1962 Russell’s friend from America, Miriam Reichl and her daughter Ruth came to tea.8Ruth, then a teenager, went on to a distinguished career as a chef, food-writer and novelist. At the height of the Sino-Indian dispute in November 1962 Indian and Chinese diplomats9came to discuss the situation with Russell (Unarmed Victory, p. 89).

There was a burglary in 1963. Russell wrote to Hepburn & Ross on 2 August that: “My house in London (43 Hasker Street), was recently entered by a burglar. He found two bottles of Red Hackle, consumed them on the spot, & thereupon considered further depredations unnecessary. I consider this a tribute to Red Hackle….”

People, some of them famous, who came to visit were photographed. In June 1963, the anti-nuclear activist, Stephanie May was pictured with Russell in front of the fireplace. In April 1964 the deputy mayor of Nazareth, Abd el-Aziz ed-Zoubai, was pictured in the back garden with Russell. In June 1964 the activists Betty and Tony Ambatielos were pictured in Hasker Street—Tony had been a political prisoner since 1945 and had just been released.

There is archival correspondence about Peter Sellers visiting Plas Penrhyn in September 1964 but nothing was confirmed. The décor of the photograph in the Archives makes it clear it was taken at Hasker Street. Russell had contacted Sellers after seeing his film Dr. Strangelove.

Russell wrote James Baldwin on 18 September 1963, praising his two-essay book on civil rights, The Fire Next Time. Baldwin visited on Wednesday 24 February 1965. There is photograph of him joining Russell for tea. There are also video images of Baldwin alighting from his vehicle and greeting Russell at the front door.10Baldwin agreed to join the International War Crimes Tribunal on 9 January 1967. In October of 1965 the singer and activist Joan Baez brought her mother to tea.11

Paul McCartney took advantage of his growing fame as a member of the Beatles to visit. Edith’s pocket diary records: Saturday 18 June 1966:“4. P. McCartney [Beatle] & Lady” and Monday 20 June, “4 McCartney & Lady till 6.30!!”. In Lyrics Paul writes that he showed up unannounced—he wanted to meet Russell “because I had always been impressed by his dignity and how well he put across an idea.” Their conversation was about the Vietnam War which Russell noted “was an imperialist war supported by vested interests … I remember going back to the recording studio and telling John about it … he hadn’t known there was a war going on in Vietnam either … that was the start of our being more aware of what wars people were involved in ...”(pp. 131-32). McCartney recollects only one visit and was not sure of the street, “Flood Street, maybe.” In 1997 Barry Miles had published his biography of McCartney based on many taped interviews. In it, McCartney recalls the visit as “nothing earth-shattering. He just clued me in to the fact that Vietnam was a very bad war, it was an imperialist war and … we should be against it” (p. 125).12So far a photograph of McCartney with Russell has not been discovered.

Russell visited London only twice in 1966. In June he opened the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign conference. On Tuesday 15 November he visited his doctor, Dr. Boyd. The next day on the 16th he delivered a statement on his International War Crimes Tribunal at a press conference in the Caxton Hall (B&R C66.44a). He did not stay for questions. A series of meetings and another visit to his doctor occupied the 17th and 18th. On Saturday 19 November he and Edith were driven back to Wales by Christopher Farley. On Tuesday 22 November he got his last catarrh injection from Dr. Pritchard. He wrote his son Conrad on 27 June 1967 that “I have grown too old to come to London except on some very great occasion.” When Desmond King-Hele visited him at Plas Penrhyn in 1968, he told him: “I don’t visit London much, because I have a complaint that prevents me walking more than a quarter of a mile” (King-Hele, p. 24). Finally he wrote to Grace Forester on 7 May 1969 noting that “nothing has taken me to London for two and a half years.” The townhouse was not given up even though Edith did not travel into London on solo visits. How she managed without her regular hair appointments is not known.

Jean Redmond became Edith’s personal shopper in London. There was regular correspondence with her from 1967 to 1969; Edith’s side is not extant. Christopher Farley did have access to no. 43 (letter of 8 May 1968). In 1969, beginning on 4 June, Jean outlined major problems with the flooring in the house; Cadogan Estates would not pay for the repairs. On 24 June, Jean wrote that no one would be able to sleep at Hasker Street for three to four weeks because of the odour. The problem was wood beetles; Green Cupinal was applied after repairs were done (A.W. Stevens to Edith, 14 August). None of Jean’s letters indicate who might have been sleeping there then. On 12 August Jean told Edith that Pamela Wood, administrative secretary of the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation, would be staying at no. 43 until she and a friend could find a flat of their own. On 19 November Jean told Edith that Anne, Russell’s granddaughter, wanted keys to no. 43. Redecoration of the sitting room was finished in late December. Anne did live there for a short period.

After Russell’s death in February 1970, Edith did not travel to London until late August, returning again in late September. In January 1971 she went to London alone for the third time. Then in March the lease on Hasker Street was put up for sale. It was purchased by Christopher Baldwin. Some of the furniture was moved to Plas Penrhyn; some furniture went to Conrad Russell; a refrigerator went to Shavers Place where the Peace Foundation’s offices were located. The movers were Lomath Brothers. Edith was there to supervise the removals. On 29 March Lomath packed what was destined for Wales in the morning and left for Wales. Delivery was expected on 30 March. The library was removed by an unknown mover to an unknown location for storage. Edith’s pocket diary, 23 March, merely notes “Chris [Farley]—Book removers for estimate.” In 1978 these books were offered for sale. McMaster University was willing to buy them but could not reach an agreement with the Peace Foundation without a listing being provided. Instead the books were put up for sale in August by a bookseller, Bibliagora, who advertised them as “Bertrand Russell’s Private Library”, a somewhat misleading description. The library was acquired by the European University Institute in Florence, Italy. In 1980-81 McMaster University attempted to purchase the books but again agreement could not be reached—the Institute would not provide a listing. I travelled there in 1986 and obtained a listing of the books. The Institute was still interested in selling them but agreement failed once again. It appears that the books have since been dispersed. The listing I obtained is in the Russell Archives.

On her trips to London after the sale of Hasker Street, Edith stayed at either Brown’s hotel or the Stafford hotel in 1972 and 1973. Her January 1973 trip to London was her last. Edith died in Wales on 1 January 1978.

© Sheila Turcon, 2025

Sources:

Desmond King-Hele, “A Discussion with Bertrand Russell at Plas Penrhyn, 4 August 1968”, Russell: The Journal of the Bertrand Russell Archives 16 (Winter 1974-75): 21-6.

Paul McCartney, The Lyrics. New York: Liveright and London: Norton, 2021.

Barry Miles, Paul McCartney Many Years from Now. New York: Henry Holt, 1997.

Bertrand Russell, The Autobiography of Bertrand Russell 1944–196, Vol. 3. London: Allen & Unwin, 1969.

Bertrand Russell, Unarmed Victory. London: Allen & Unwin, 1963.

Archival correspondence: Louis P. Tylor, Roy E. Brooks, Jean Redmond, Peter Sellers, James Baldwin, Grace Forester.

Internet Sources

Lord John Russell’s bust at Westminster Abbey

- 1

Russell sent Brooks £90 on 6 November.

- 2

Edith to the Electricity Board, 10 Dec. 1958.

- 3

Coward Chance letter, 12 September.

- 4

Russell to G.F. Pollock, 11 Oct. 1958.

- 5

A dimensions drawing in the Edith Russell papers; an image appears in Additional photographs.

- 6

18 Dec. 1958; since a new tenant would not be moving into the flat there was no urgency.

- 7

The Westminster bust has the goat from the Russell coat of arms but includes a motto which has no connection to the Russell family.

- 8

“Old Friends”, document .313299.

- 9

On Saturday November 17 the Chinese Chargé d’Affairs visited; on Monday 19 November the Indian High Commissioner arrived.

- 10

I captured screenshots from a video in 2022 but neglected to note its title and have not been able to locate or identify it.

- 11

“Friends & Visitors”, document .313300.

- 12

Tony Simpson is working on an article “When Paul McCartney met Bertrand Russell”; once it is published details will be provided here.