41 Queen’s Road, Richmond and 29 Millbank Road, London

In 1950 Russell returned to Richmond. As he explained in his Autobiography, his son John and his family were “living near the Park in a tiny house,1much too small for their family of three little children. My son told me that he wanted to give up his job and devote himself to writing. Though I regretted this, I had some sympathy with him. I did not know how to help them as I had not enough money to stake them to an establishment of their own in London while I lived in North Wales. Finally I hit upon the scheme of moving from Ffestiniog and taking a house to share with my son and his family in Richmond” (3: 69). Russell was forced to leave his Welsh house because it belonged to his estranged wife, Peter, and she had sold it.

“Returning to Richmond, where I spent my childhood, produced a slightly ghostly feeling, and I sometimes found it difficult to believe that I still existed in the flesh … I had hoped vaguely that I might somehow rent Pembroke Lodge and install myself and my family there. As this proved impossible, I took a largish house near Richmond Park, turning over the two lower floors to my son’s family and keeping the top two for myself. This had worked more or less well for a time in spite of the difficulties that almost always occur when two families live at close quarters” (Auto. 3: 69, 70). The house is a short walk from the gates to Richmond Park and the road that leads to Pembroke Lodge. When Russell began his love affair with Ottoline Morrell he wrote to her on 25 April 1911 that “It would be nice to go to Richmond Park, where I belong—” On 17 April she asked him to meet her at the British Museum so they could go to Richmond together. His love affair with Constance (Colette) Malleson began in 1916. The couple visited Richmond Park on her 21st birthday, 24 October. It appears once he married Dora in 1921 there were no further visits to the Park. This may explain the ghostly feeling he had when he returned in 1950.

Richmond Park in 2013

In 1948 he had written to Gilbert Murray about his concerns about Pembroke Lodge—that letter appears in my Pembroke Lodge article. Once he was living in Richmond he wrote: “Pembroke Lodge, which used to be a nice house, is being ruined by order of the Civil Service. When they discovered what they did not know until they were told, that it had been the home of two famous men, they decided that everything possible must be done to destroy its historic interest … Later, I changed my opinion of their proceedings and thought that they had done the adaptation very well if it had to be done” (Auto. 3: 69).

On 9 July 1949 Russell wrote to Colette that “John plans to take a house & let off flats, & in that case I may join in with him to keep the rent in the family. He gave up his job in the Civil Service in order to write, & has at the moment no income. He is absolutely set on writing, & I think will write well, but needs financial help. If I take a flat in his house, I shall be totally independent.” Independence was important for Russell. To her friend Phyllis Urch, Colette commented on 27 November: “He will be o.k. with John and wife for some little time, but will find it unsatisfactory in the long run, I expect … all the experience of the last thirty-four years points to him starting some new connection, and way of life.” She was going to cancel the London meeting they had planned for 6 December, trying to remove him from her life once and for all.

The details of the purchase of the home in 1949 are not known. John wrote to his father on 12 January 1950 that “It is melancholy that the repairs to the house are going to take so long; but when we went over it with the builders it was obvious that it could not be done properly in a short time; and that it would not be habitable until all the repairs were done, and the damp out of it.” On 3 March Russell wrote to his daughter Kate that “Some optimists maintain that the Richmond house will be habitable before I die.” On 11 March John wrote to his father again saying that a target date to move into the upper two floors was 23 March. He had been answering job advertisements. He hoped to get a job paying £10 a week by June. In the meantime he needed financial assistance. On 21 March 1950 L.P. Tylor of Coward Chance & Co. wrote to Russell that the builders’ original estimate for their work was £2,179, not including “the various fittings which have had to be put in hand and which have been selected by John and Susan.” Costs had now risen to £2,783 including the bookshelves. Not included was fencing and putting the garden in order. John planned on paying £100 a year in rent beginning in June once he obtained employment as well as “two thirds of the electricity bills and one half of the rates.” It is not clear how Russell financed this not inconsiderable sum.

John, Susan and their three daughters moved in before Russell did. On 7 April 1950 Susan wrote: “We were wondering if you would like to come to stay here in three weeks’ time.... John and I are very anxious to have you here, and start our house running all together.... We expect to move downstairs at the end of two weeks, and expect to have completed the essential furnishing at the end of three weeks.” On the same day John wrote to his father, telling him that the phone was now in as well as the bookshelves. He asked for £388 to cover basic furnishings as well as a “fence for the back garden where the wall is down….”

Russell wrote to Kate on 11 April 1950: “I am going to Richmond on May 1st. I think I shall like it. John & Susan are very glad to have more room; the children were terribly on top of them. I find John’s company very agreeable.… He would be utterly sunk if I did not help him financially.” He followed this letter up on 21 May, telling Kate that: “It is very nice living here—we have a lot of good talk, & I love the children.” This is at odds with the statement he published in his Autobiography: “I suffer also from entering into the lives of John and Susan. They were born after 1914, and are therefore incapable of happiness.… If I had not the horrible Cassandra gift of foreseeing tragedy, I could be happy here, on a surface level. But as it is, I suffer” (12 May 1950, 3: 89).

BR in the back garden

John’s three daughters were named Anne, Sarah, and Lucy. Each girl was photographed individually with their grandfather reading to them. Through the window the spire of the nearby St. Matthias church on King’s Road can be seen.2On the wall is a print by Edward Fisher of Lady Elisabeth Keppel. It has been taken to Carn Voel and will be on display there in the near future. One of photographs appears below. The other two photographs appear in Additional Images. Absent from Russell’s life during this time period was his son Conrad. He had been removed by his mother, Peter.

Lucy with her grandfather

Russell maintained a correspondence with Irina Wragge Morley (later Stickland) who had looked after him on Grosvernor Lodge, informing her of his relocation plans. She was often invited to visit. Her first visit in fact was to be in January before he had moved in. The house would be “full of workmen, and mostly unfurnished. I hope to get the place in order soon, but nothing gets done till one is on the spot” (7 Jan. 1950). It appears she did not take up this invitation as on 16 June he wrote that it was a “pleasure to see you again & I hope it was only the first of many visits.” She did visit again over the next couple of years. On 4 May he invited his Welsh neighbours, Elizabeth and Rupert Crawshay-Williams to visit. “My suite here contains a single bed in one room & a double bed in another, so I can put you both up at any time. John & Susan have made the house very pleasant & comfortable.” There may have been several visits.

During his time at Queen’s Road, Russell was often away. From June to August 1950 he was in Australia on a lecture tour. John wrote to him there on 7 July from 1 Daleham Gardens, London telling his father that he was “having a complete rest from everything—no Susan, no children, no job …” Susan was in Harlech. John was in “analysis, calming down, and feeling steadier …” He had written to “Susan yesterday suggesting she look for a furnished bungalow or cottage in Wales for the summer, with the aim of sending the children & Griff [the nanny] & Frances to her, for the summer.” John noted that the reason for this plan was that he was concerned about war and thought his family would be safer in Wales. The family reconnection on Queen’s Road had been fractured for the moment; it is not known who was maintaining the house but presumably domestic staff.

In the autumn Russell was in America to lecture and learned that he had won the Nobel Prize for Literature. He visited his daughter Kate in Washington, D.C. and also re-connected with Edith Finch. “Unexpectedly friendship developed into a warmer relation. Our mutual love has, since this happened, been the chief source of my happiness—a very profound happiness, such as I had not expected to know during my remaining years” (Autobiography typescript, p. 653; 210.007054-F6). In December 1950 he travelled to Stockholm for the Nobel ceremonies while Edith moved into Brown’s Hotel. On 15 February 1951 she rented a flat at 6 Paradise Walk, London SW3 (document 311544). On 24 May he wrote to Edith about the many extramarital affairs of John and Susan. “I alone am stable but I feel giddy with all these changes.” Susan was in Paris, he does not say where John was. The autumn of 1951 Russell went to America on a lecture trip; it was his last visit there. Edith accompanied him to Greece in April 1952.

When he was at home at Queen’s Road there were visits from friends including Daphne Phelps, Gogi Thompson and Lion Phillimore, as well as visits from journalists and photographers. The Reichenbachs from America were there for lunch in September 1953. Other visitors included the Huxleys, the Themersons, and the Catlins. The Chaos, whom he first met in China, came for tea on 22 October 1954. Edith typed up lists of their social appointments titled “Old Friends” and “Friends and Visitors” (documents 313299 and 313300). She noted guests they entertained at home as well as outings. On 10 March 1953 they lunched at the Athenaeum in London with Arnold J. Toynbee and his wife. “T. insults Alexandrian Greeks; B points out that Christ was not the inventor of the motor car.” Freda Utley came to tea in both 1953 and 1954. He re-connected with his first wife Alys though it appears she did not go out to Richmond but he visited her in Chelsea. She died in 1951.

On 28 May 1951 he told Edith that he had “a secretary 6 days a week, & am just starting an autobiography.” His period of residence at Queen’s Road was very productive— Russell published a number of books: Unpopular Essays (1950), The Impact of Science on Society (1951), New Hopes for a Changing World (1951), Satan in the Suburbs (1953), and Nightmares of Eminent Persons (1954). Most of Portraits from Memory and Other Essays (1956) was written during the Queen’s Road period. Also dating from this time is the pamphlet Man’s Peril from the Hydrogen Bomb (1955; first broadcast on 30 December 1954). The Autobiography would not be published until much later.

Staff at the Queen’s Road house included Lillian Griffith, the children’s nanny, and a Mr. Weatherley. In a letter of 30 October 1952 to Elizabeth Crawshay-Williams, Edith mentioned a maid called Dinah (Russell Remembered, p. 73). When Russell told Dinah Avery4that he was going to marry Edith, “She expressed the warmest sentiments about you.”5On 29 November the sculptor, Jacob Epstein, wrote to Edith telling her that he would “love to do a bust of Earl Russell, not as a commission but” because of his “interest in the subject.” He knew Edith because he had done a bust of Lucy Martin Donnelly, Edith’s companion, in 1931. Russell agreed and the sittings began in December. Mid-way through the sittings Russell and Edith married on 15 December in the Registry Office at the Chelsea Town Hall.

Another visitor in 1952 was his friend Nalle Kielland who had sent her children to Beacon Hill School. She wrote about her visits to Colette. “I can well understand that B. wanted to give them [his son’s family] a proper place to live, so that John could possibly do his other work out of office hours.... In a way they live apart now, B. has his own servant to look after him, and the others have their ménage apart.... B. with young children is a wonder. He enjoys them, and they adore him of course....” Nalle also noted John’s odd behaviour of constantly playing an accordion, not realising that this was the start of his descent into mental illness from which he would never recover (16 Jan. 1952). On another visit she met Edith and found her “charming and loveable” (19 Feb. 1953).

Romney Wheeler, an American journalist, interviewed Russell in early 1952, before Russell’s 80th birthday in May. The interview was filmed by NBC and broadcast on that network and also on the BBC on 18th May.6The programme began with views of Richmond followed by the outside of the house. The interview appeared to take place in Russell’s home. But in fact Wheeler had visited the home on 21 January and declared it unacceptable because of the “noise from low flying aircraft” and “the amount of equipment necessary.” He proposed shooting in Viking Studios where “a simple dignified set resembling a library” would be built (4 Feb. 1952). The interview was filmed on 18 February. The film ends with a view of a revolving bookstand holding some of Russell’s books, including New Hopes for a Changing World. It is similar but not the same as Russell’s own revolving bookstand which is now in the RA.

Screengrab of house front

India House first approached Russell about a photograph. He replied directly to the photographer, Jikandra Arya, on 30 May 1952 indicating his willingness to be photographed. Arya visited on 9 July. He sent three images on 8 September. Russell’s verdict on the pictures: “I think they are excellent, especially the larger one & the one in which I am lighting my pipe.7The third is no doubt a very good likeness but the expression is a trifle milder than I like.” One of the photographs from this session appears in Auto. 2: 204.8Volume 2 ends in 1944 so the inclusion of this photograph is odd. His pocket watch chain is visible in the images.

BR photographed by Arya

Ray Bradbury visited in 1953. He arrived on 11 April for tea. Tim Madigan has described the visit which was prompted by a Harold White photograph of Russell with Bradbury’s book Fahrenheit 451 beside him, which he sent to Bradbury’s publisher. Bradbury’s recollection of the visit was shaky in parts. He described Edith as staying in the background knitting—this was an obsession of Russell’s third wife, Peter. It is unlikely a very sugary and milky tea could have been served—Russell drank the very strong and smoky Lapsang Souchong. Bradbury summed it up as a nice meeting although he never felt really at ease with Russell.

BR with Bradbury’s book beside him, photo by Harold White

Julie Medlock, Russell’s American literary agent, visited him in Richmond in 1953. She described the house as “a four-storey cream coloured brick house9set behind a low brick wall and a white wooden gate, in a small garden with a flagstone path …” (Medlock, p. 49). The top two floors where Russell lived contained: “a commodious bedroom and bath, a small booklined study, and another book-lined living room which faces the deep back garden. From its huge window, one glimpses trees and lawns, neighbouring English houses and gardens, the steeple of a nearby church,10and a great, changing, expanse of sky. The furnishings are simple, comfortable, worn. There is a heavily-laden desk, a daybed stacked with papers and books yet to be read, and, grouped around the fireplace, a tea-table, sofa, and two deep armchairs with lamps beside them for reading ease” (Medlock, p. 50). Russell’s love for children shone through. John’s three children visited and he amused them with stories and tea cakes. He felt “They give me hope for this world….” (Medlock, p. 51). These town homes are described as Park Villas designed by the architect T N Reeve in a Dutch style built in 1850 (Richmond Historical Society). There is some resemblance to the canal homes of Amsterdam.

BR taking tea with Julie Medlock

He and Medlock visited the nearby Richmond Park. In an interview with The Wichita Beacon she quoted Russell about the garden. “I rarely close my eyes at night without remembering the beauty of this garden.” During the walk he spoke about the many trees that grew there: “oaks, beeches, horse and Spanish chestnut, limes and cedar”, as well as two Lombardy poplars. Russell and Edith often walked in the Park which “was full of reminiscences, many going back to early childhood. Relating them revived their freshness … I recalled all sorts of things that had happened to me there” (Auto. 3: 64). He acquired an Ordnance Survey Map of the Park. In it Edith recorded “Sites Known to BR in Childhood ff.” The map is now in the RA.11During the time Russell lived in Richmond, the Russell primary school which had been destroyed in World War II was rebuilt. It was named after its founder Lord John Russell.

Trees in 2012

On 24 January 1953 Jacob Epstein wrote to Russell that “the model is now at the founders, being cast in bronze.” It was ready on 25 February with Epstein pronouncing it a very fine one. On 3 March Russell replied noting that he wished to visit the studio to decided what sort of pedestal would suit it. Ida Kar photographed the studio. Two images appear in her book—a portrait of Epstein and one of Russell with the bust in the background.12

A party at Queen’s Road to celebrate Russell’s birthday was attended by Lewis Croome.13“Epstein’s bust of him was presented by Edith and the guests (who included Ayer and Rattray Taylor) were given copies of BR’s Nightmares then just published.” Since Nightmares was published in May 1954 I can only assume that Croome has conflated two birthday parties into one. The party which included the presentation of the bust must have taken place in 1953. Croome noted that “the Epstein bust14was of course much bigger than the bust of Voltaire which I remember being on the mantelpiece at Richmond always.” He and his wife were then living in Claygate, Surrey. “BR when living at Richmond came over here, alone or with Edith (who … Honor and I had met … long before she married BR and when she was teaching at Bryn Mawr) … I used to drive to Richmond (while Honor got dinner) to collect and return them and he would tell stores all the way. He was a splendid raconteur, especially about his early life with his grandparents at Richmond.”15There are two notations in Russell’s Pocket Diary, 8 April and 14 October 1953 noting dining appointments with the Croomes.

BR looking at the Epstein bust, photo by T.A. Morris

Edith’s tenancy at 6 Paradise Walk was terminated on 12 February 1953. She and Russell decided to maintain a pied-à-terre in London renting a first-floor flat at 29 Millbank Road SW1 on 8 February 1953. Millbank runs parallel to the Thames in Westminster. Decades earlier he had lived in Chelsea in a home with a view of the Thames. The freehold owners of 29 Millbank were the Commissioners for Crown Land. Russell sub-let the property from a Miss George. Russell dealt with this property through the estate agents, Chesterton & Sons. In May 1956 the annual rent was £200, paid quarterly, plus the rates. At this time she agreed to extend the lease from 17 May 1957 to 14 December 1958.16 Presumably they enjoyed their time away from Queen’s Road. Trips into London for appointments would be time-consuming. They liked going to the theater (Auto. 3: 66) which involved overnight stays. In March 1953 Russell invited the Crawshay-Willamses back to Millbank for a drink after dinner at Hatchett’s. In June of that year they let Julie Medlock stay there during the Queen’s coronation. She noted it overlooked the Thames and was near the Tate Gallery and the Houses of Parliament (Medlock, p. 175). In April 1954 Jacob Bronowski drove them to Millbank after they attended a rowing race on the Thames.17In an undated letter to Elizabeth Trevelyan Edith wrote about “Julian and Mary’s Boat Race Party.”18 Russell and Edith spent the weekend at Millbank after the presentation of the Russell—Einstein manifesto in July 1955 (Auto. 3: 78). Unfortunately there are no photographs of the Millbank building or flat. It was demolished in 1958 and replaced by the Millbank Tower. See Hasker Street.

“At Christmas, 1953 … My son and his wife decided that, as she said, they were ‘tired of children’. After Christmas dinner with the children and me,19they left, taking the remainder of the food, but leaving the children, and did not return” (Auto. 3: 70–1). Nalle Kielland was back for another visit in January 1954. “Edith looks well after his house, I think, which he needs, the 3 girls were home for the holidays.... He read to the children every evening” (5 Jan. 1954). Shortly after that visit Russell was admitted to hospital for prostate surgery and there were complications as Edith told Elizabeth Trevelyan in a series of letters. At the same time the ceilings had fallen down and had to be repaired. On 1 February Edith feared that Russell would have to go to “our tiny flat in Millbank” once he got out of hospital. By February 9th the ceilings had been repaired and all was ready for his return home. By mid-February he, however, had developed a fever from an infected stich and was unable to leave. By 28th February Edith could tell Elizabeth he was finally home and well enough to go on a walk “a little way into Richmond Park in the sunshine.” By late 1954 Edith was acting as Russell’s secretary. She told Elizabeth Trevelyan on 25 February 1955 that his mail had “become colossal” and that the household was “in its chronic state of disintegration” because of domestic staff problems. At the same time John’s health was deteriorating; this development was “hideously harrowing for Bertie” (4 March 1955). On 14 March 1955 Dr. Desmond O’Neill wrote that John, who was living with his mother, Dora, was “at times quite helpless and childlike” and required “almost continuous care.” On 5 June 1955 O’Neill visited John in the Holloway Sanatorium in Virginia Water, Surrey and informed Russell by letter the next day.

In 1955 a home in Wales, Plas Penrhyn, had been found by Rupert and Elizabeth Crawshay-Williams after two years of looking (Russell Remembered, p. 101). This house would be a rental and leasing agreements were made with the owner, Sir Osmond Michael Williams. The Russells spent time there but their main residence was still 41 Queens Road until it was sold the following year. Edith noted it as a holiday house beginning 24 June 1955 (document 311544). They spent summer holidays there that year as well as Christmas. In an undated letter written before Easter in 1956 to Elizabeth Trevelyan Edith wrote that “we are trying to sell our house in Richmond as we think one house is all we can keep going, and the house in North Wales seems from all points of view the best to hang onto.”

On 1 June 1956 Edith wrote to Elizabeth Trevelyan: “I may have written you that we are selling this house and planning to move to North Wales, and at the same time we hope to put the grandchildren in a new school nearer us there. All this has entailed an incredible amount of fuss.” A valuation of some of the contents of the Queen’s Road house was done that month by Hampton & Sons Ltd. because Russell did not want to take all his possessions to Wales. It gave a room count: on the top floor were a front bedroom, back bedroom, cistern room and kitchen; on the first floor a right back room, bathroom, right front room and library; on the ground floor a hall, front bedroom, back bedroom and cloakroom; in the basement, a hall, right front room, back room, kitchen, and a passage cupboard.20

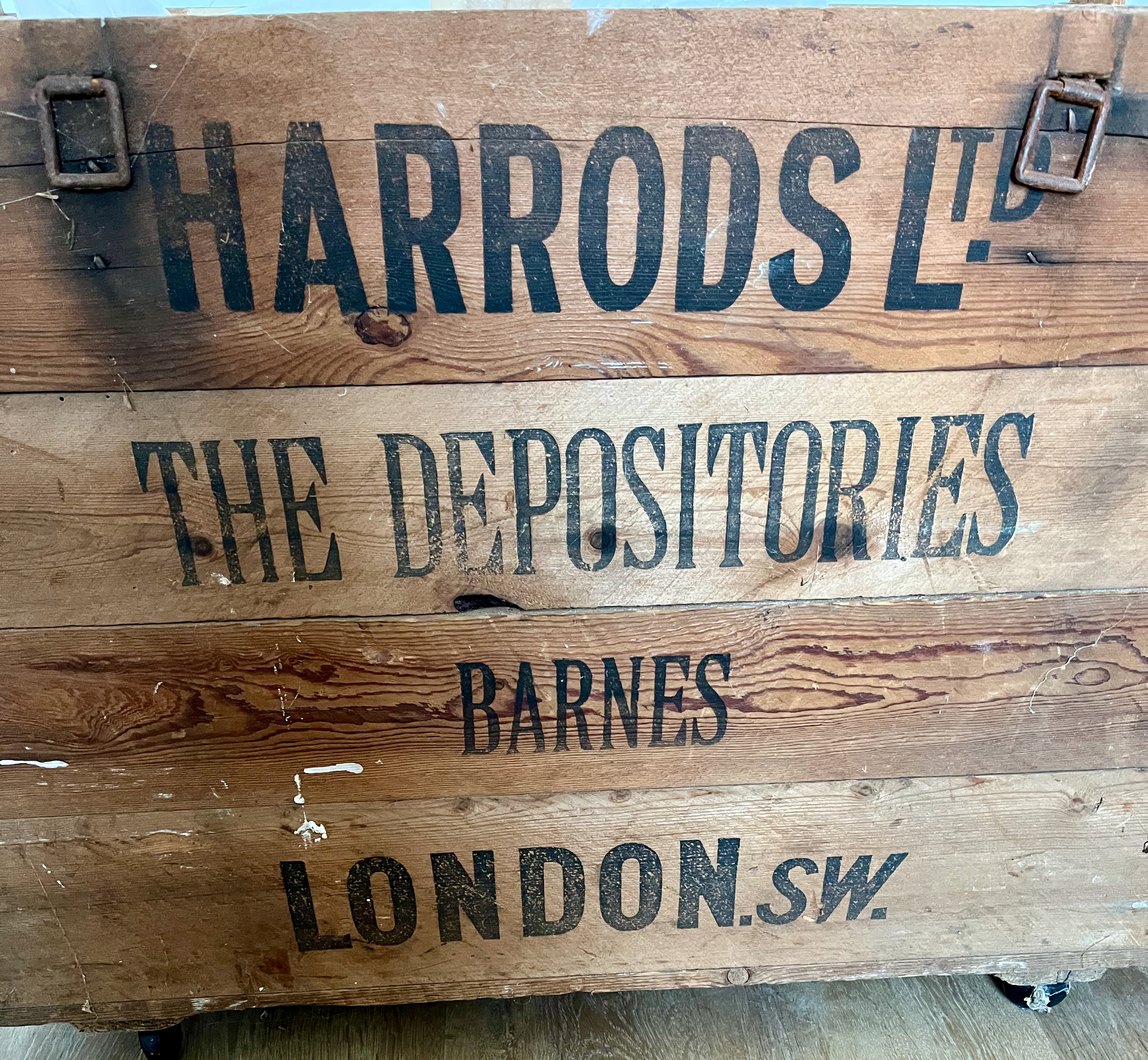

Dennis Rosen was supposed to buy the house and he viewed it on 4 June. The sale fell through and Edith noted on 28 June that the house would be open for viewers all week.21She expressed her annoyance to Elizabeth Trevelyan that they had to pack “amongst streams of strangers pouring through the house with a view to buying it.”22The house was sold to Dr. J. R. Seale23in July, with a closing date of 11 August 1956.24In the earlier sale, Russell was willing to leave £2,000 on mortgage at 5 ½ %.25The move to Russell’s new home, Plas Penrhyn, in North Wales, was handled by Harrods Ltd. in nearby Barnes. One of the packing trunks used has survived and it now at Carn Voel. Packing began on 2 July and unpacking ended on 6 July. A carpenter from the Harrods Building Department took down the book-shelves and divided them into manageable sections. Russell wanted to be at his new home to receive the goods, including the Epstein bust. His possessions were insured for £4,000. He and Edith left Queen’s Road on 5 July 1956 (document 311544).

Harrods packing box

On 22 July Russell wrote to Dora: “As regards 41, Queen’s Road, I know how John loved the house at first and I hoped that he and Susan would settle down there, but it became evident that Susan would not settle anywhere. Both she and John left the house … without even telling me that they were doing so. Some months after … I asked John point-blank if he thought of coming back and he said he did not … You seem to blame me for having sold the house, but I cannot understand on what ground. John and Susan had both refused to live there, and, without them the house was unnecessarily large and awkwardly planned for a single household.” He told Dora that he was “having serious difficulties in meeting expenses” which included the support of John and his children.26The sale of Queen’s Road was a way to raise capital.

I visited the house in 2012. Queen’s Road is a very busy street and it was not possible to stand in it to get a photograph of the whole house, which is quite tall. Trees also shelter the house. I noticed a plaque on the house. I used my zoom lens to read it: “Bertrand Russell / Philosopher / Lived Here / 1949–1956”. It is not an official blue plaque; presumably it was put up by a later owner. The 1949 date refers to the date of the purchase by Russell, not the date when Russell moved in. I returned to photograph the house again in 2023 with a superior camera. It was in much better shape, with the trim re-painted. The plaque remains in place.

House plaque

The Queen’s Road experiment of multi-generational family living had ended. His son’s family had shattered. Yet Russell had found new love after a bitter divorce and was both active and productive during the half-decade he spent in Richmond. He was ready to begin his final chapter in Wales, the place of his birth. His ties to London were not cut, however, as he maintained his flat on Millbank Road until 1958 when the building was demolished and later replaced by the Millbank Tower.

House in 2023

© Sheila Turcon, 2024

Sources:

Rupert Crawshay-Williams, Russell Remembered. London, New York: Oxford U.P., 1970.

Ida Kar and Val Williams, Ida Kar: Photographer, 1908–1974. London: Virago, 1989.

Tim Madigan, “Tea and Bradbury”, Bertrand Russell Society Bulletin (Fall 2023: 3–7).

Julie Medlock, “Bertrand Russell: So Fondly Remembered”; typescript in RA.

Julie Medlock, “Early Years Important to Lord Russell”. The Wichita Beacon, 19 March 1951, p. 7.

Caroline Moorehead, Bertrand Russell: a Life. London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1992; Griff is identified as the nanny, p. 497.

Bertrand Russell, The Autobiography of Bertrand Russell 1914-1944, vol. 2. London: Allen & Unwin, 1968.

Bertrand Russell, The Autobiography of Bertrand Russell 19441967, vol 3. London: Allen & Unwin, 1969.

Sheila Turcon, “Richmond Park”, Bertrand Russell Society Bulletin (Fall 2022: 4–7).

Archival correspondence: Constance Malleson, Ottoline Morrell, Katharine Tait, Susan Russell, John Russell, Edith Russell, Nalle Kielland, Desmond O’Neill, Dora Russell, Lewis Croome.

Internet Sources:

Gillian Dunks on Lucy Russell.

Romney Wheeler, “A Conversation with Bertrand Russell (1952)”.

Charles Pineles on the social history of Queen’s Road, Richmond.

Russell School

Jacob Epstein

Photo of St. Matthias Church credit

- 1John’s house was at 19 Cambrian Road which ran from Queen’s Road toward Richmond Park. This street is very close to 41 Queen’s Road.

- 2Lucy’s papers are now in the RA. Gillian Dunk has written about them—see Sources.

- 3Edith Russell recorded an overnight stay on 17 November 1954 (“Old Friends”, document 313299).

- 4A note in Christopher Farley’s hand in a file indicates that Dinah was the cook (30 Dec. 1957).

- 5Letter to Edith, 22 October 1952.

- 6“A Conversation with Bertrand Russell”. B&R, C52.13; B130

- 7This photograph is in the RA Photograph collection.

- 8The photograph is in RA Archives 4.

- 9When I photographed the house in 2012 it had red brick walls with white trim, as did all the adjoining townhomes. Another visitor, possibly a daughter of Learned and Frances Hand described the house as white (Rec. Acq. 1581). The home has unpainted natural brick in the Romney Wheeler 1952 NBC programme.

- 10St. Matthias on King’s Road.

- 11See my article listed in Sources.

- 12Her photograph is also in Auto. 3.

- 13He was married to Honor (1908–1960), one of Mildred Minturn Scott’s daughters. Honor was an accomplished economist and novelist. Croome (1907–2008) was head of the British Food Mission in Ottawa, Canada, during World War II. The couple also spent a year in Massachusetts.

- 14Kenneth Blackwell remembers seeing the bust at Plas Penrhyn. That bust is now owned by the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation. In October 1980 another cast of the bust came on the market and McMaster purchased it. According to Wikipedia four casts were made. Another casting of the bust is on display at British High Commission, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. The plaster is at the Israel Museum, in Jerusalem.

- 15All quotations in this paragraph are contained in a letter to the author, 21 July 1983, Rec. Acq. 805.

- 16Three letters from L.P. Tylor to Russell, May 1956; document 311544.

- 17“Friends and Visitors”, document 313300. This document noted more than one attendance at these boat races, indicating that Russell may have retained an interest in rowing long after his days at Trinity.

- 18At Durham Wharf in Hammersmith, the home of the Trevelyans.

- 19Edith was absent from the dinner because she had the flu.

- 20Document 762.113146. The goods, valued at £659, were sold in June 1956. Edith noted on the document that Dinah bought 2 tables and a refrigerator.

- 21“Friends and Visitors”, document 313300.

- 22Letter of 10 September 1956.

- 23His name is also spelled with an “s” on the end in some archival correspondence

- 24L.P. Tylor to BR, 16 July 1956.

- 25Dictated letters of 2 June and 10 July 1956.

- 26Russell’s divorce from his third wife had also been costly.