Russell returned to Britain shortly after D-day in June 1944 on a Liberty ship making its maiden voyage. He had been away since the autumn of 1938. His wife Peter and son Conrad had travelled across the Atlantic before him on the Queen Mary. Arriving at the “northern shore of the Firth of Forth ... I got a night train to London, arrived very early in the morning, and for some time could not discover what had become of Peter and Conrad. At last, after much frantic telephoning and telegraphing, I discovered that they were staying with her mother at Sidmouth [Devon] ... I went there at once” (Auto. 3: 15–16).

Daphne Phelps remembered the Russells’ return in 1944. She had stayed with the Russells in America, both in California and Pennsylvania. “Peter and Conrad arrived during a lull in the bombing and came to stay in my London flat. I remember his half-brother John, later the fourth Earl Russell, turning cartwheels on my bomb-site garden in the uniform of a naval AB [able seaman] to amuse Conrad, then about five. There seemed to be real affection between the three. Bertie followed in a still later convoy, and they rented a flat in Marylebone” (A House, pp. 177–8). She is correct about the flat although the Russells did not rent it until 1946.

Russell took up a five-year lectureship at Trinity College.1The appointment came with rooms in College. Leaving his family he found “that the rooms were altogether delightful ... but the problem of housing Peter and Conrad remained. Cambridge was incredibly full, and at first the best that I could achieve was squalid rooms in a lodging house. There they were underfed and miserable, while I was living luxuriously in College” (Auto. 3: 16). It was a recipe for marital conflict if there ever was one.

Grosvenor Lodge, 6 Babraham Road, Cambridge2

As soon as Russell was confident in receiving money from his lawsuit against Barnes he bought a house (Auto. 3: 16). He wrote to his publisher Stanley Unwin about the house purchase on the 4th of August 1944 asking for an advance of £500 on History of Western Philosophy, which Unwin had already promised. By now Peter and Conrad had lived in a series of temporary places in the United States and in England. Peter must have been pleased to have a new home to decorate despite the constraints of post-war Britain. There is no correspondence outlining her decorating choices. On 21 August Russell wrote to Elizabeth Trevelyan that he had purchased “a small house, but can’t get into it for another month.” The exact date of purchase and the seller are not known. He described the house on 20 September to his former lover, Colette,3as “small & commonplace, but the garden is nice. It is practically in the country, & the country near is pleasant. I had to buy as there is nothing to rent….” On 30 September he wrote to daughter Kate, that “We shall in a very short time be able to put you up in our house if you don’t mind some discomfort. Peter means to make nice rooms for you and John when possible, but at first they will be unfinished.”

He wrote to Colette again on 8 December 1944 that the location of his new home “is rather far to walk [to Trinity College], but there is a bus every 12 minutes … Conrad flourishes and likes his school and our garden … I lecture on Philosophy and Politics to the many, and on scientific method to the few. Also I do some broadcasting for the B.B.C.” Grosvenor Lodge was located south of the city centre. It was built around 1929.4

Russell did not choose to join his wife and son in the autumn of 1944 once they had moved into the house, but remained at Trinity College. He told Wallace Brockway at Simon & Schuster on 7 September 1944 that he enjoyed being back in Trinity. He told Colette on 20 September how much he liked the experience. “I dine in hall & enjoy seeing dons I used to know 30 years ago. George Trevy [Trevelyan] is much mellowed, very friendly, & nice.” Trinity College gave him a refuge from life in a house “not yet habitable for me” (letter to John Russell, 30 Sept. 1940).

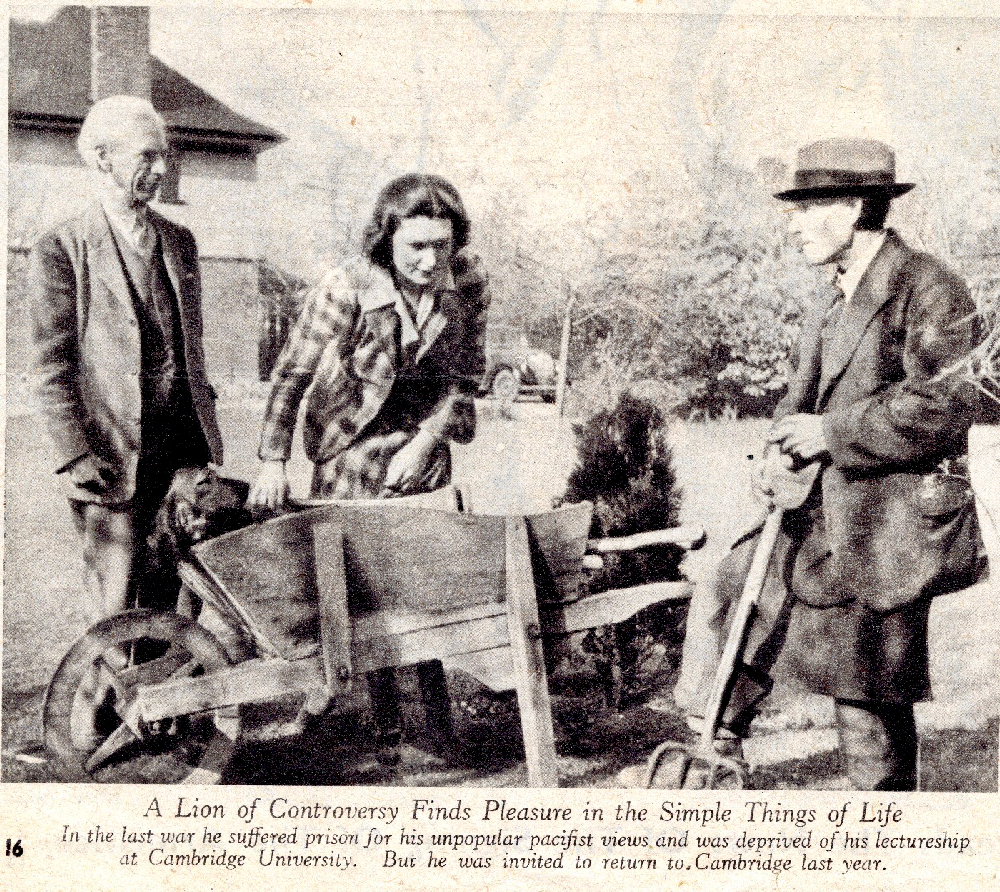

Russell, Peter and Conrad in the grounds of Trinity College, taken for Picture Post

Peter and Russell were photographed by K. Hutton both inside and outside the house for a Picture Post article in 1945. An inside photograph was captioned “A Fireside Recital. In slippers by his fireside, Bertrand Russell reads poetry to his wife.” Russell is standing while Peter is seated on a sofa; an oriental rug, bookshelves, and a standing lamp surround them. This poor quality image can be seen in Additional Images. Although not identified the couple on the porch (below) must be Russell’s children, John and Kate, who had both returned from the United States.

Russell and Peter at Grosvenor Lodge; John and Kate on the porch

It was at Grosvenor Lodge that Russell “wrote most of my book on Human Knowledge, its Scope and Limits. I could have been happy in Cambridge, but the Cambridge ladies did not consider us respectable. I bought a small house at Ffestiniog in North Wales with a most lovely view” (Auto. 3: 16). The actual predicament was more complicated than Russell indicated. On 14 April 1945 Russell asked Clive Bell to visit them for tea in Cambridge. “Peter is prevented by war-time household ties from going out except on rare occasions.” This seems to me a very odd situation.

Peter wrote to Elizabeth Crawshay-Williams on 15 October 1945 that they had sold Grosvenor Lodge that day and were “feeling a little panicky. We must have somewhere else to live before next August.” They wanted to move to Wales, near the Crawshay-Williams5and she asked for Elizabeth’s help, although she didn’t want to over burden her. Peter had been in the house for barely a year, Russell less than that. Russell wrote to Stanley Unwin on 6 December 1945 that he was selling the house even though it was already sold. A week later on 15 December he told Gamel Brenan that Grosvenor Lodge had been sold. They did not have to move out until July. Russell told his daughter Kate Tait on 11 January 1946 that he had bought a cottage at Ffestiniog and he would be leaving Grosvenor Lodge on 31 July.

Russell told a far grimmer tale about the situation at Cambridge in private correspondence than he does in his Autobiography. On 7 February 1946, he wrote to his friend Gamel Brenan that “as soon as Peter got away from Cambridge she began to feel better. Slavery to housework has caused her to feel a gradually increasing envy of me—my work, my friends, my success, my popularity. She fought against the feeling but in the end it overwhelmed her & she had a serious nervous breakdown, culminating as I told you. The Doctors had to work over her for a long time, in doubt whether she would survive; the police came to question me but were persuaded it was an accident. When she found she was still alive she was very unhappy & incredibly bitter; from moment to moment I feared a repetition, which she threatened. Now it is settled she will go to N. Wales, perhaps with Conrad … Conrad will become a border at Dartington [Hall School] in September.” With Peter away at a nursing home in London, Russell remained at Grosvenor Lodge. “A married couple (with twins), who are friends of ours, have moved in, and relieve me of housekeeping” he told Gamel. They were Derek Wragge Morley and his wife Irina.6Irina wrote about Russell. Her comments survive in a typescript of numbered points. Some of them concern the time she was living with him in Cambridge. She first noticed him as “a small upright old man with a shock of white hair … He was stepping briskly with a boy of eight or nine” (number 1). She mentions that a chicken had escaped from the garden (number 10a). Irina notices that he “was accustomed to be looked after” and had not realized he had no tooth-paste which she had to provide (number 27). She had to look after his clothes to keep him presentable. “He used to read every evening the passages that he had written in the morning” (number 30).

Russell asked Rupert Crawshay-Williams on 17 February 1946 to look after Peter who would be staying at the Pengwern Arms until the cottage was ready. “My wife, who has been in a nursing home, is now back here [i.e. Grosvenor Lodge], but by Doctor’s orders is going to Wales tomorrow. She has been very ill indeed and now needs a complete rest from household, parental and wifely cares … Conrad and I will join her when the Easter holidays come.” On 22 February he wrote to Gamel telling her that “I can never again live in the same house with Peter when I am working, as she wears me out, but I hope to be able to manage Conrad’s holidays with her, for his sake. She was here last week-end to pack up, & is now in Wales. When I am with her she spends all the time weeping, & explaining over & over again exactly how I have ruined her life, but when I am absent she is gay.” On 10 March 1946 Russell wrote Kate that “Peter is gone to live in N. Wales, and we shall only be together during Conrad’s holidays. In the autumn I shall get rooms in College. As the family disintegrates, your affection is an increasing comfort to me.”

Once again Russell turned to Trinity College for refuge from a complicated life. From Trinity, he wrote on 13 October 1946 to Colette: “… I shall not be here after Christmas, but with Peter in a tiny flat in London. This is a change of plans which became unavoidable.” He expands on this in his letter of 8 December 1946: “My job here continues, & I shall be here one night in every week during term; the rest of the time in London in winter, N. Wales in summer.”

The last known letter that Russell wrote from Grosvenor Lodge was dated 4 April 1946.

Dorset House, Gloucester Place, London

On 8 November 1945, Peter wrote to Elizabeth Crawshay-Williams who was helping her find a place in Wales that she had been in London looking for a flat while Russell was doing the BBC Brains Trust. There was nothing to be found and she theorized that perhaps she would have to live full time in Wales with Russell living in College during term time. On 15 December 1945 Russell wrote to Gamel Brenan that he and Peter were planning “to get a pied-à-terre in London.” Hotels were impossible to get, so a flat in London would be necessary. It is not clear when the Russells sub-let a flat from Sidney Cowen. Cowen signed a lease with Metropolitan Housing Corporation on 29 September 1945 for unit no. 27. The yearly rent was £240, payable quarterly (Rec. Acq. 1343).

Dorset House contains 185 flats in the Marylebone7area of London, occupying a complete city block. It was built in 1934–5, by the architectural firm, T.P. Bennet and Son, with consulting help on design from Joseph Emberton. Dorset House is considered to be one of the most impressive Art Moderne style buildings in central London.8Apsley Cherry-Garrard, the Antarctica explorer, and his wife Angela, had a flat there. His biographer described the building in detail. The flats “were aimed at wealthy types who had better things to do than eat in, and as a result they all had pokey little kitchens … theatrical people and minor members of the royal family” lived there. “Because of its multitudinous wings and winglets it did not have miles of institutional corridors … it was a friendly place, with attractive modern features such as central heating and letter chutes in which tenants could deposit their mail.” The Cherry-Garrards were on the sixth floor, one floor below the Russells. “Like a cruise ship, the building was self-contained. The ground floor was encircled by small shops that included a newsagent, a fishmonger, a chemist, and a grocer with a dairy to which milk was delivered by pony and cart … porters sat in a cubby-hole adjacent to a spacious art deco entrance hall lined with couches, and glass double doors opened onto a restaurant” (Cherry, pp. 272–3).

Frederic Raphael, born in 1931, saw Russell in the restaurant although he is incorrect about the date and his age as he was 11 in 1942. His grandmother lived in Dorset House. “I first saw, and heard Bertrand Russell when I was 11 years old … my mother and I were placed, at lunch, at a table next to Russell and his schoolboy son Conrad … when the boy asked him whether having learnt Greek would assist him in mastering Sanskrit, Russell said ‘I have a fancy that Welsh might be more pertinent’ … My only other recollections of that distant day are of the zeal with which Russell spooned his carrot soup and of his philosophically dashing white hair” (Prospect). Raphael later attended Russell’s last lecture in 1949 at Trinity College when he was 18 years old.

Occupying a ground floor flat from 1942 to 1947 were the filmmakers Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger who ran their production office from the premises. They were honoured with an English Heritage blue plaque in 2014.

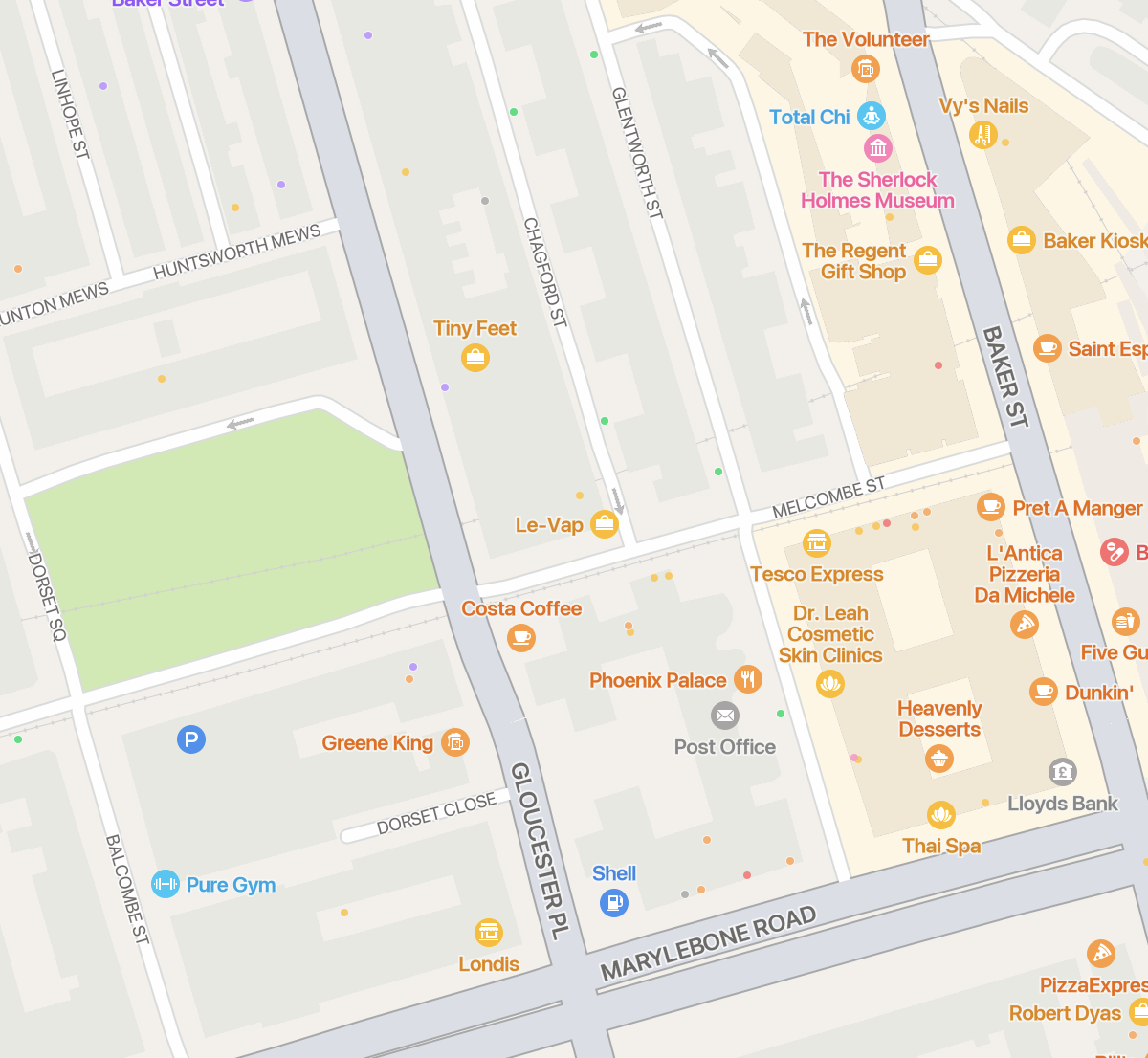

I visited Dorset House in August 2023. Even today it looks very modern. The ground floor contains many small shops, restaurants and a Shell gas station. It is a block from the Baker Street Tube Station and is bounded by Gloucester Place, Marylebone Road, Glentworth and Melcombe Streets. Regent’s Park is just to the north. It is a lovely neighbourhood though busy in 2023, and a distance away from Russell’s old haunts of Chelsea, and Bloomsbury—though nearer to Bloomsbury. Russell had last rented a London flat in Bloomsbury while living at Telegraph House. It was a departure for Russell to rent a flat in such a large building.9The entrance to Dorset House is off Gloucester Place; the stone relief sculptures flanking the entrance are by Eric Gill.10I entered the lobby, spoke with the doorman, and photographed the interior as well as the building from all four sides. The building is centered around a higher level courtyard and has indentations. Restoration of the front entrance face and foyer interior was carried out in 2020 by London Stone Conservation Ltd. One of the photographs that I took is below. Others, as well as maps, appear in Additional images.

Dorset House in 2023

Russell noted in his Autobiography the purchase of a flat (3: 16). In a paragraph that was written for the Autobiography but not published he noted: “The years during which we shared a flat in London were difficult and unsatisfactory. Peter’s purely hysterical hostility would flare up from time to time, making daily life uncomfortable. I spent much time in visits to the Continent for purposes of lecturing, but I did no work of importance during these years. At last, as was inevitable, there came a definite breach. For me at least this was a great gain.”

Russell sent out his first known invitation to lunch at Dorset House to Karl Popper. Written on 30 November 1946 from Trinity College, Russell suggested the date of Monday 2 December. The first known letter that Russell wrote from his flat was dated 8 December 1946 to Unwin enclosing a paper-bound copy of History of Western Philosophy with corrections noted for a reprint. Three other letters written that day were sent from Trinity College. He spent more time at this London flat that he did in Cambridge, writing of his weekly train journey from London to Elizabeth Trevelyan on 11 January 1947. On 8 August 1966, Dorothy F. McLendon, an American school psychologist wrote to Russell about Marriage and Morals. She added that she would never forget the lunch they had shared at Dorset House in the Spring of 1947. She had been accompanied by her husband, Hiram.11On 25 June 1947 Russell described the flat to his daughter Kate, who had returned to the United States, as having a “living room, bedroom, kitchen & bath. The living room has a divan bed.” He reassured Kate about his living conditions. “Your newspapers much exaggerate our discomforts. It was unpleasant during the great frost, when we had to economize fuel; otherwise, we have no sufferings. There is plenty of food, and there are more things in the shops than there were.”

On 20 February 1948 Lucy Donnelly wrote to him: “Are either of your elder children still in America? Conrad of course will have grown beyond my recognition. Will you not send me some word of them and of Peter … Even the London where you are living is almost unknown to me …”12A photograph of the Russells walking with their dog in London, presumably near Dorset House appears below.

Russell, Peter, and Conrad in London

Peter and Conrad in London

An invitation to visit the London flat for lunch went out to Grace Wyndham Goldie of the BBC on 26 January 1948. The writer-journalist J.L. Hammond and his wife received an invitation on 25 March. Russell explained he would be at the flat from 20 April to 21 May. “During the summer I have to go to Holland (twice), Sweden, and Norway.” On 18 August he wrote to Gamel, wanting to see her: “I shall be in London (at Dorset House) after Oct. 12 all through the winter, except for a brief visit to Berlin if there is no war.” On 21 September he sent a letter to Elspeth Fox Pitt inviting her to visit in London after October. The following year Colette visited on 7 February (Pocket Diary), writing to her friend Phyllis Urch on 12 February 1949 from Russell’s Welsh cottage where he would join her in March. “I did not know BR had just given his last broadcast13when I saw him. He opened the door to me and said nothing about it. Their flat is a palace, a small one: I mean in furnishings, not size. Conrad was in bed listening to his private radio with the dog on his bed. Peter was in her scarlet Welsh housecoat over pale green sweater with a bad sore throat & cough. BR was as usual.” On 15 February Russell wrote to Ralph Hawtrey: “It would be very nice to see you some time and if you are ever at leisure, perhaps you could propose yourself to lunch here. There is a restaurant in the building, so that an unexpected visitor causes no inconvenience.”

The Russells did employ a cook at Dorset House, Lena Walsh. Her daughter, Mary Chesters, wrote to Russell around 1967 to thank Russell for the happy memories. Russell allowed Mary and her two sisters to use the bathroom as they did not have one at their own home.14Her letter reveals Russell as a generous employer, treating Walsh’s children to many excursions including nearby Regent’s Park where Conrad capsized a rowing boat, Hampstead Heath, Epping Forest and Pembroke Lodge. She asked if he remembered the cocker spaniel he gave her (document .110365). In late 1948 the Russells moved from no. 27 on the seventh floor to no. 18 on a lower floor; the reason for this move is not known. The last letter Russell wrote from this address was dated 22 April 1949 and addressed to Charlotte Kohler of the Virginia Quarterly Review.

Russell had a connection to this property until 1951. He had worked out a plan with his wife Peter to let her remain at the flat in return for him staying in Wales until 1950. On 5 July of 1951, L.P. Tylor of Coward, Chance & Co. wrote that: “The flat was duly let as from 24th June … dilapidations etc. amounting to £100.8.1 [are owing]. Perhaps you would kindly send a cheque direct to the Landlords.” On 17 March 1952 Russell wrote to Tylor asking him to inform Guardian Assurance Company that he no longer had a flat at Dorset House.

Kenneth Blackwell received an email from Nick Hopewell-Smith on 22 November 2010. He saw Russell’s third floor flat when it was put up for sale six years before that by a retired Warner Brothers executive. No. 18 was “virtually unchanged since the 30’s, complete with the original (quite terrifying) electric heaters and built-in electric clock and the original butler’s quarters.” In a follow-up email of 23 November he changed his mind about the location of no. 18. “It seems the flat I visited must have been on the fifth floor (no. 18). No. 27 was a large flat on the seventh floor and now split into two flats ... Both 18 and 27 are on the Dorset Square/Melcombe Street corner of the building.”

© Sheila Turcon, 2023

Sources

Rupert Crawshay-Williams, Russell Remembered. London: Oxford U.P., 1970.

Daphne Phelps, A House in Sicily. New York: Carroll & Graff, 1999.

Frederic Ralphael, “Russell in the Bushes,” Prospect (19 May 1996), available online.

Bertrand Russell, The Autobiography of Bertrand Russell 1944–1967, vol. 3. London: Allen & Unwin, 1969.

“Bertrand Russell on the Problems of Peace,” Picture Post [London], 27, no. 3 (21 April 1945): 16–18.

Archival correspondence: Stanley Unwin, Elizabeth Trevelyan, Constance Malleson, John Russell, Katharine Tait, Gamel Brenan, Rupert and Elizabeth Crawshay-Williams, Simon and Schuster, Mary Chesters, L.P. Tylor, Peter Russell.

Archival documents: “Dorset House. BCM Chartered Surveyors Report”, November 2010.

“DHTA Report: News and Views from the Dorset House Tenants Association”, September 2010. This newsletter notes Bertrand Russell’s occupancy of a flat. These publications were donated by Nick Hopewell-Smith; they can also be found online.

Irina Stickland, “Bertrand Russell”, Rec. Acq. 357.

Sara Wheeler, Cherry: Life of Apsley Cherry-Garrard. London: Jonathan Cape, 2001.

Personal emails: from Nick Hopewell-Smith to Kenneth Blackwell.

Internet sources

Grosvenor Lodge

Entry for Dorset House on Historic England

- 1There is a separate article on Trinity. In this article I reference Russell living there to provide context to the time spent at Grosvenor Lodge, the home he bought in Cambridge.

- 2There are several mentions of a house in Wales in this article. It will be covered in the next article in this series.

- 3The stage name of Constance Malleson.

- 4See web link in Sources.

- 5The Russells had met Rupert and Elizabeth Crawshay-Williams through Amabel Williams-Ellis when they visited Portmeirion in the late summer of 1945 (Russell Remembered, p. 1).

- 6They are identified in the BRACERS transcription of this letter. Irina's last name changed to Stickland when she later married L.H. Stickland. Her birth name was Platonov.

- 7Also in the Marylebone neighbourhood was BBC Broadcasting House in Portland Place.

- 8There is a wealth of information about this building online—see Sources.

- 9The only other large block of flats he lived in was Overstrand Mansions with Clifford Allen in 1919.

- 10The sketches for this work are at UCLA.

- 11McLendon taught at Homerton College Cambridge, 1946–47.

- 12This letter is printed in Auto. 3: 41 misdated as 1945.

- 13Presumably the last Reith Lecture on 30 January 1949.

- 14There were maid’s lavatories on each floor for use by staff.