Plas Penrhyn, North Wales

Russell and his wife Edith relocated to North Wales in 1956 from their home on Queen’s Road in Richmond after using it as a holiday home in 1955. Their London base continued to be their flat on Millbank Road, a property they had rented since 1953. When it was demolished in 1958 they rented a townhome on Hasker Street. Russell had lived in North Wales before. In 1933 and 1934 he stayed with his future wife Peter in the village of Portmeirion.1Then in 1945 they bought a home, Penralltgoch, in Llan Ffestiniog.

It took some time to find a new place to live once Russell and Edith had decided to leave Queen’s Road. In 1954 Russell wrote to Frances Williams2on 14 April: “I remember the house that you mean, but I do not at present wish to live in Wales as it is too far from London.” On 23 February 1955 estate agents, the Chamberlaine Bros., contacted Edith with regard to the sale of a home in Coln Rogers, near Bibury, Gloucestershire. Edith’s note on the top indicates she was interested and wanted photographs and the price. But later that year Wales entered the picture.

On 5 May 1955 Edith wrote to their friends, Rupert and Elizabeth Crawshay-Williams, enclosing an advertisement for a house near Portmadoc, Wales.3This house turned out to be unsuitable. According to Rupert, he and Elizabeth had been looking for houses for the Russells since 1953 and they were the ones to find Plas Penrhyn. It was “a Regency house with its own grove of beech trees … and—best of all for us—was only five minutes’ walk away” (Russell Remembered, p. 101). Regarding the arrangements made to lease the property, there is a letter, 26 July 1955, from the owner who lived nearby, Sir Osmond Michael Williams of Borthwen, Penrhyndeudraeth,4 enclosing the lease, which has not survived. There is a letter from R.C. Jones & Sons, estate agents, 27 October 1955, listing a rent of £50 quarterly. Percy A. Popkin noted in a letter to Russell of 20 February 1956 that Russell had rented Plas Penrhyn since 22 June 1955. For the first year Russell also spent time in his Queen’s Road home in Richmond not moving permanently to Plas Penrhyn until July 1956 when the Queen’s Road home was sold.

Aerial Image

Edith wrote with excitement to her American friends Judge Learned Hand and his wife Frances, whom she called Jay and Fanny, on 7 June 1955 from St. Fillians, Perthshire in Scotland:5“On the way up here we stopped with the Crawshay Williamses & found a house with most beautiful views over Portmeirion harbour to the open sea and up the valley to Snowdon which we are renting so as to have a place in the country for the children’s6holidays. It is deep in the country but within easy walking distance of the little village & the hotel & lots of Bertie’s old friends—among them the Crawshays.… It’s quite a large house so we wish you’d come & see us there. It will have to have another bathroom put in & the brambles dug out of the front lawn. But it has lovely fireplaces & views & all essentials & a kitchen garden & an orchard & a woodland & a potting shed & a tiny glass house & the only neighbour is the farmer who supplies eggs & milk etc., & there is even a village daily & a gardener—so, if it turns out right, we’re in clover! We rent it unfurnished, but the man who is moving out will sell up cheap all of his furniture (some of it perfectly charming & all of it good Victorian) that we want to buy.…”7The house was located in Penrhyndeudraeth. Edith went full steam ahead with preparations to make the house habitable. On 25 June 1955 she told Elizabeth Crawshay-Williams that she had bought furniture, cutlery, and linens from various London stores which were being shipped north. A list was enclosed.

After the summer of 1955 was over Edith wrote on 18 October from Queen’s Road to Elizabeth Trevelyan. She explained that they had taken the house to provide holiday time for their grandchildren. It would also provide a place for their “future holidays.” The “house was habitable for the children by mid-July, and in mid-August we joined them there for a glorious six weeks.” Russell had been extremely busy with “meetings and speeches, plans, discussion, article and Conferences” in London and Paris earlier that summer. Once in Wales “we enjoyed ourselves greatly so that the perfect maelstrom of work into which Bertie had now plunged doesn’t seem quite as appalling as it did.” At this point there was no plan to move there permanently. They spent Christmas there with their granddaughters and others. It appeared that the cook would not be available as Edith wrote to Elizabeth on 26 November: “I look forward with some trepidation to cooking a Turkey for 10 or 12 people in an oven into which it probably won’t fit.”

Rupert Crawshay-Williams noted that the house “belonged to a neighbour and friend … in several of the rooms there was a window directly above the fireplace.… There was a small conservatory on the outside wall of the drawing-room, which Bertie and Edith filled with masses of flowers set up on shelves.… From the other window, which was a half French window with steps up and down to the verandah, there was a marvellous view of Snowdon …” (Russell Remembered, pp. 101-2; “several” is possibly an exaggeration).

Russell in his Autobiography described it as being “small and unpretentious, but had a delightful garden and little orchard and a number of fine beech trees.… I was captivated by it, and particularly pleased that across the valley8could be seen the house where Shelley had lived. The owner of Plas Penrhyn agreed to let it to us largely, I think, because he too is a lover of Shelley and was much taken by my desire to write an essay on ‘Shelley the Tough’9….” The house would be ideal for the children, “especially as there were friends of their parents10living nearby whom they already knew and who had children of their own ages” (Auto. 3: 71-2). When Russell had lived in a hotel in Portmeirion owned by Sir Clough Williams-Ellis he wrote to Miriam Reichel on 11 Oct. 1933: “We are living at a hotel belonging to a friend: he buys up the country-houses belonging to his impoverished cousins, & turns them into hotels that have none of the bad qualities of conventional hotels. He makes a mint of money. His mother, who is 82, lives in the house Shelley inhabited at Portmadoc, & speaks of ‘Mr. Shelley’ as if he were a country neighbour.” Shelley was in residence in 1812-13. The house, Plas Tan-Yr-Allt, is now run as a country house where rooms can be booked (see Sources).

Russell on verandah with estuary, photo by T.A. Morris

Two of his biographers, Ronald Clark and Caroline Moorehead, noted the importance of both the view and Shelley. According to Clark, Russell found “on certain days of the year … the setting sun appeared to roll down the hills beyond the estuary, a natural phenomenon that delighted him”(Clark, p. 551). Moorhead had a negative opinion about the house. It “like almost every house he lived in, was neither very comfortable nor very attractive. The furniture was in ginger-colored wood, there were no good pictures, and the atmosphere was purposeful and hardworking, but a little cheerless”(p. 498). I find this assessment rather harsh. Another biographer, Ray Monk, wrote practically nothing about the house.

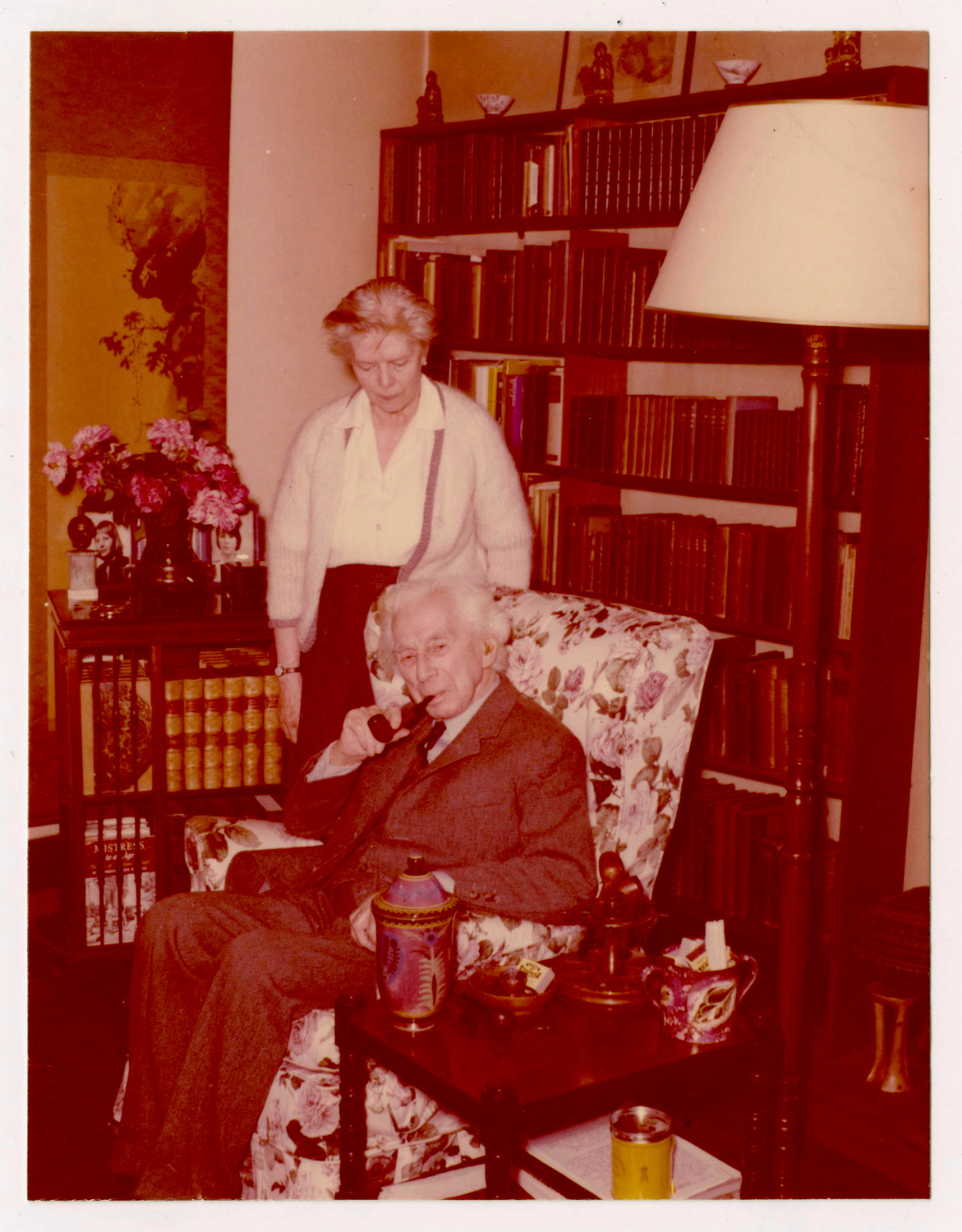

Edith and Russell inside; Lord John bust on bookstand

Being such an old property meant that many people had lived there before. Sir Lewis Casson wrote to Russell on 24 November 1959 that it “was the first house my father and mother lived in when they were married (at Penrhyn church) in the late [eighteen] sixties!” They had moved on before Casson was born. The Victorian novelist, Elizabeth Gaskell, honeymooned there in 1832. The British Listed Building website notes: “In 1827 Samuel Holland (1803-92), industrialist and owner/manager of the Gloddfa Ganol slate works at Blaenau Ffestiniog, moved to the house to which he added the Regency (NW) wing”. Gaskell was his cousin. The Cadw Listed Building site notes that “Plas Penrhyn began as a late C17/early C18 storeyed vernacular house.”

Once the decision was made to turn this holiday house into a permanent residence, Edith wrote a detailed list of furniture at Queen’s Road. Marked beside each item was a letter: S meant “Sure Take”, U meant “Unsure”, N meant “No”. Oddly enough this list is written on printed letterhead of 5, St. Leonard’s Terrace, Chelsea.11Three Wittgenstein tables were marked “N”. It is not known what happened to them; perhaps they went to Millbank Road. Two Pembroke Lodge tables were marked “S” (document .311873, Box 2.26). The decision was made sometime before Easter 1956. Edith told Elizabeth Trevelyan that they could not keep both Queen’s Road and Plas Penrhyn: “the house in North Wales seems from all points of view the best to hang onto.” Edith took care with the décor. Fabric and carpet samples from Heal & Son can be found in her archives.

A house as large as Plas Penrhyn required domestic staff, even if the new residents had not been old and still very busy with work. The job positions included a cook; either a daily or live-in maid, often two of them; a nurse/housekeeper, later a housekeeper/cook; and a gardener. These positions were not all held by the same people during Russell’s tenure. Some had to be let go while others decided to leave. When Nell Morgan was let go because of health problems, Edith explained the dilemma in her dismissal letter of 12 December 1963: “We like … to be able to have visitors here even when the children are at home.… We also should like to have someone here to answer the telephone on fine afternoons when we wish to go out ourselves … we feel that we must get someone to live in and be our housekeeper-cook, as you have been … the work is piling up and difficult for Mrs. Griffiths and Mrs. Edwards even with Mrs. Thomas’s occasional help….” A Mrs. Humphreys left because “the job [was] too monotonous” and the stone floor too hard on her legs (document .311857, Box 2.26). National insurance cards had to be maintained for all staff. They were treated well if they needed help.

The first gardener, Richard Osborne, wanted geese. One gander and three purebred Chinese geese were ordered from C.F. Perry in Somerset on 14 November 1955. Perry’s motto stamped on the envelope was: “Every country home should have a flock of Chinese geese.” The cost was £20. There were also a rabbit and guinea pigs, which the gardener had to feed and keep their houses clean (document .311872). Peanut the dog entered the scene in 1962. According to Edith’s pocket diary, she was born on 24 February 1962 with the name “Choc. Pud.”; she listed hers along with the other family birthdays. Russell and Edith noted on 29 May that Pudding had been renamed Peanut.12Nell Morgan (domestic staff) and Peanut sent a happy birthday telegram to Russell at Hasker Street in May 1963. The previous year Edith had written to Nell from Hasker Street that “We miss her sadly here, however undeniable it is that life is easier in these close quarters without her” (24 Aug. 1962). On 25 September 1964 Peanut had a male puppy (Edith’s pocket diary; it is not known what happened to this offspring). Peanut appeared during Desmond King-Hele’s visit in 1968 but was confined to the verandah because she was too dirty to come in—she had been running in the sea-mud (King-Hele, p. 23).

Edith and Russell with Peanut, photo by Gamel Brennan

Renovations to the property took place in 1956. In June a garage was erected.13Before the Russells arrived in July, work was to be done on “the two attic rooms and the room above the scullery, especially the enlarging of the skylights, … on the greenhouse and the roof of the verandah.”14Consideration was giving to building a maisonette in 1960 designed by Clough Williams-Ellis but was rejected as too expensive.15

Edith told Elizabeth Trevelyan on 9 February 1957 that they were loving living in Wales. “It is a heavenly place and one in which Bertie finds it easy to work.” On 4 March she wrote that Russell’s health was improving and his throat almost back to normal. “It really is superbly beautiful. We have lived in a world of enchantment these last days, with daffodils and primroses blossoming and black birds singing and lambs gambolling.” Despite all these delights Russell had been writing several articles. On 12 March she wrote that: “There is a Hungarian painter downstairs making a drawing of Bertie. I suppose he will make B. look Hungarian. They all make him look like someone of whatever nation” they come from.

Russell lived a full and productive life in his old age, writing over 10,000 letters from Plas Penrhyn as well as many books. Portraits from Memory and Other Essays was published in 1956. Why I Am Not a Christian followed in 1957. In 1959 Common Sense and Nuclear Warfare, My Philosophical Development and Wisdom of the West appeared. Fact and Fiction and Has Man a Future? followed in 1961. Unarmed Victory was published in 1963; War Crimes in Vietnam in 1967. Over a span of three years, 1967-1969, his Autobiography in three volumes appeared.

Russell and Edith were accepted into the community. In 1960 Russell was listed as one of nine Vice-Presidents of the Miniffordd Club. Another Vice-President, Michael Burn, from Beudy Gwyn became a friend. His landlord, Sir Osmond Williams, from Borthwen, was the President. The club offered social evenings including a scotch evening, dinners and talks. At Christmas there was a debate on whether Christmas was commercialised too much. After Russell died, Burn wrote about their friendship: “He gave us so much delight … It is in the warmth of love that we shall remember him”.16

Many people made the long trek from London to visit Russell. He sent the following directions to Yuan Ren Chao, his former Chinese translator, on 24 September 1968 which ended with: “Pass the post office (on the right at the junction) and take the turning 200 yards further along on the left. This narrow lane leads upwards towards Plas Penrhyn, which is half a mile from the main road.” Russell wanted signs put up on the main road to mark the entrance. The nearby farmers had to agree, which they did.17Kenneth Blackwell does not recollect seeing any signs and the letter to Chao does not mention them. However, the signs did exist; Tony Simpson of the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation sent me an image of one of them. A different sign marked the house later; Andrew Bone photographed it in 2018. Chao and his wife, Buwei, did visit and Chao described their visit in an article in the Russell Journal. Rupert Crawshay-Williams in Chapter 7 of his book listed many people who visited both couples. They included John and Celia Strachey, Marghanita Laski and her husband John Howard, Margaret Storm Jameson and her husband Guy Chapman, Robert Boothby, Woodrow Wyatt and his wife Moorea, Julian and Juliette Huxley, Charles Laughton and his wife Elsa Lanchester, and John Gilmour. Russell met Ingrid Bergman who was filming The Inn of the Sixth Happiness in Portmeirion in June 1958.

Russell sent an invitation to Brand Blanshard and his wife to visit in 1959. After a visit in 1959 Helen Hervey sent Russell a book of her father’s poems, She Was My Spring (Russell Library 1461). Zora Lasch who used to teach at Beacon Hill School and her newspaper editor husband Robert also visited in 1959. Grigor Lambrakis and Manolis Glezos, Greek activists, visited in 1963. Glezos recollected that “Russell received us lying down on a chaise lounge.”18His American friend, Miriam Reichel, visited in June 1963. After one 1964 visit Victor Purcell sent an effusive thank you to Edith on 23 May: “Plato, Socrates, Gibbon, etc. would have been too opinionated to make congenial hosts, Jesus or Buddha would have bored me, and Alexander, Napoleon, and Jinghis would have been conversationally ineligible.” In May 1965 a group of Indian Trade Union leaders came to Plas Penrhyn. Desmond King-Hele visited on 4 August 1968. He found Russell a charming and witty host. Mansel Davies, who lived about six miles away, made day visits and was served China tea. These visitors represent just a fraction of the people Russell welcomed to Plas Penrhyn. People who worked for Russell also spent time there: Christopher Farley, Ralph Schoenmann, and Kenneth Blackwell among them. During his visit Blackwell noted that in one corner of the room where he listed the books, a small television was perched on the top of the shelves. It was never on.19Anton Felton, Russell’s literary agent, also visited.

Indian Trade Union leaders, photo by British Information Service

Ray Monk quotes from David Horowitz’s memoir of a visit he made in November 1966. Everyone there was connected with the Peace Foundation, “all were under 25 years of age … the great man had outlived himself. All his friends were dead, and the world that had been his was gone” (p. 149). Monk rightly pointed out that “it was not quite true, of course, that all Russell’s friends were dead, but his circle was getting smaller” (p. 499). Of course this happens to everyone as they age.

Russell’s daughter Kate, her husband, Charles, and their three children20visited but she does not give the year. Russell put them up at the Portmeirion Hotel; despite its size Plas Penrhyn was too small to accommodate them all comfortably. Kate describes her father as sitting “in his armchair by the fire, with his feet on the same lovely old rug, surrounded by his ivories and his Chinese paintings, his books and the remembered friends of my childhood, just as he had always done.… I felt his greatness more then, as we sat quietly over tea … than at any other time” (My Father, p. 193). “Sometimes we walked in the garden after tea, enjoying the velvet lawn, the opulently exquisite flowers and the view across the estuary to the mountains … every day [there was] a tea party with my father and Edith. It was so overwhelmingly luxurious that I was almost embarrassed; it did not suit my conception of our relationship to be treated with such lavish generosity by my father” (My Father, p. 195.) There were in fact two visits, both in July, one in 1960 and one in 1961 (Edith letter to Hotel Portmeirion, 19 May 1961).

Russell’s reconciliation with his son Conrad took place at Plas Penrhyn after almost two decades of estrangement. Conrad wrote to him on 24 June 1967: “I have just finished reading your autobiography, which I found very interesting and enjoyable, and often curiously familiar even when it was dealing with things I knew nothing about. It has made me feel that I really would like to see you again, and this feeling goes much deeper than it did before.” On 27 June Russell replied that he was glad “there is no longer a breach between you and me. I shall be glad to see you and your wife.” By this time Russell was no longer travelling to London. Conrad and his wife, Elizabeth, stayed in Portmeirion. Conrad had “pleasant memories of you associated” with Portmeirion (letter of 2 July). He and Russell must have spent time there when they lived at Penralltgoch, in Llan Ffestiniog. After July, Conrad and Elizabeth became regular visitors. Conrad had not seen his father since 1951 when he was still a child. Whether he knew in advance that reaching out to his father would result in estrangement from his mother is unclear. But that was the result. Monk wrote he defied his mother in seeing his father (p. 499). On 30 July Conrad wrote: “I was also very glad to meet Edith again. I remembered her from America, but my memories were very shadowy, and I was pleased to find how much I like her.” During a September visit Conrad climbed Moel Hebog. “There is a very good view of your house from the top. It must be very nice to have a house which is so visible from all the mountains, and so invisible from the all the roads” (11 Sept.)

Russell’s health was generally good as he aged. On 18 May 1967 his 95th birthday was celebrated with champagne and a birthday cake served to “18 old friends & relations from London & 8 neighbours” (Edith pocket diary.) On 1 October Russell was feeling breathless and Dr. Prichard was sent for. Russell was to stay in a downstairs bedroom for a week; a nurse visited every day. On 6 October Edith wrote to their landlord: “We are anxious to install a small lift in Plas Penrhyn at the earliest opportunity, following advice from Dr. Prichard … The structure of the house would not be altered in any way, but some minor alterations would be necessary. On the ground floor it will be necessary to remove the pantry door and the small wall to its left … A new retaining wall … will be necessary. On the first floor, we would seal the present bathroom door and make a new door between the bathroom and our bedroom. At the same time we would make a new doorway between our bedroom and the adjacent bedroom, convert our present bedroom doorway into a cupboard and seal off the end of the landing beside the lift. (The new bedroom doorway would permit the moving of heavy furniture and the use of a wheelchair if it should ever be necessary.)” Then on 21 November Russell was diagnosed with pneumonia. On 9 December it was decided to have one of the nurses live in. On 3 December Edith wrote to Conrad regarding a Christmas visit. She told him an elevator was being put in so Russell would not have to climb stairs once he recovered from his illness. The house was in a mess with floors up, holes in the walls and “everything is … sixes and sevens.” She recommended delaying his visit. On 12 December Russell told Conrad that he had “been very ill, in fact, dangerously ill. I am now beginning to recover.” Conrad still wanted to visit and on 17 December sent a telegram that he would arrive in Portmadoc on the following day. His wife Elizabeth sent a thank you letter, noting that “it was a Christmas we shall remember for a long time.” Russell was up and walking again.

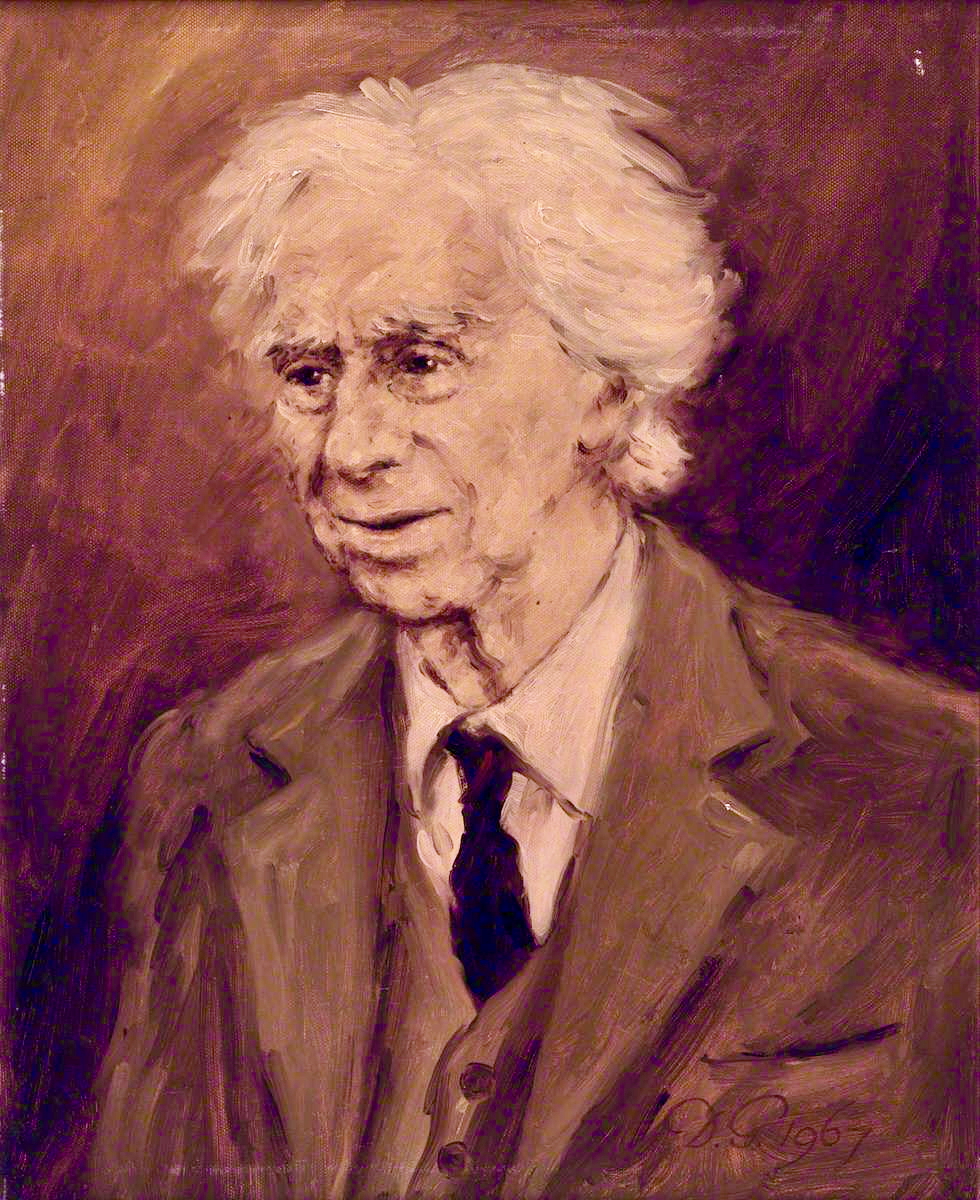

On Monday 4 September 1967, a young Cardiff artist, David Griffiths, arrived to paint Russell’s portrait. “It was painted in one morning, and Mr. Griffiths tried to capture Lord Russell’s wisdom, tempered with his humour.” After Russell’s death Griffiths was pictured with the painting in the South Wales Echo. He remembered that Russell liked the portrait “but thought it made him look old.” It is now housed at the National Library of Wales—it was donated by Dr. Hugh S. Price in 2006.

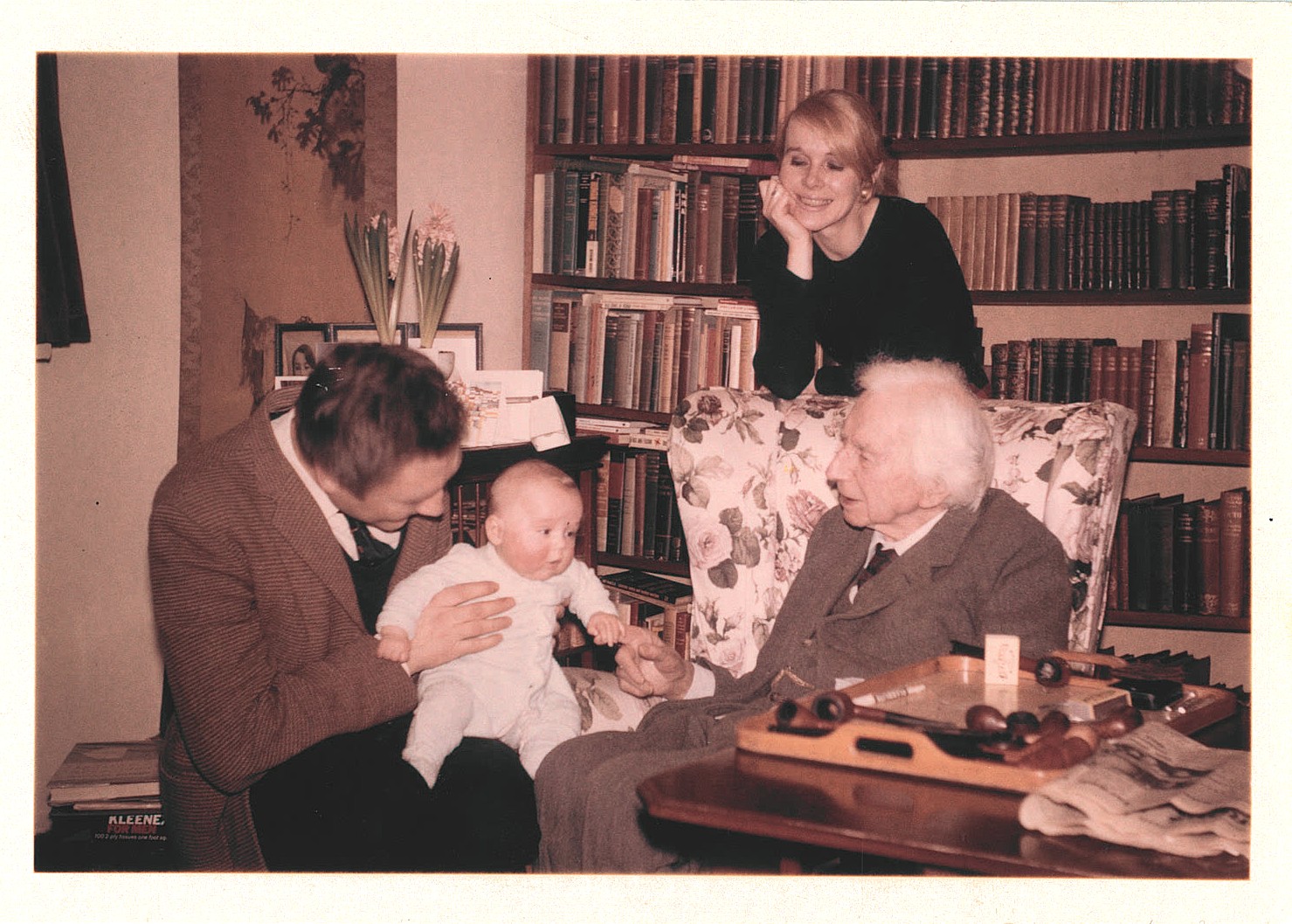

Elizabeth became pregnant, giving birth to Nicholas Lyulph, in September 1968. On 14 September Conrad asked permission to borrow the family high chair which he had used. Conrad eventually gave the chair to Pembroke Lodge where I saw and photographed it. Conrad wrote about his father’s rapport with Nicholas and included a photograph of them together in “My Father Bertrand Russell”. Conrad and his family were there to celebrate what turned out to be Russell’s last birthday on 18 May 1969. Later that year, on 17 October, Edith wrote that Russell had fallen and although he was recovering well he was “not yet able to see visitors.”

BR, Elizabeth, and Conrad with the baby; snapshot by Edith

In 1968 Edith used her pocket diary only to record birthdays, anniversaries and so on. There is no pocket diary for 1969. She did, however, write a letter to Constance Malleson on 14 February detailing his health matters. “What irked him the most was that he was unable to walk any great distance and that his eyes were going bad … At Christmastime he had a very bad cold from which he recovered. Then, towards the end of January another germ attacked him. He seemed to be getting rid of it … Bertie got up after lunch and we sat in our bedroom talking and having tea and reading. Suddenly, he was sick. The young man who has been living here during the past half-year and I got him into bed and he seemed all right again. I sent for the doctor, but he could not come till too late. Bertie felt no pain, he said, but he had difficulty in breathing. We gave him oxygen, but it did not help.” He died later that day, on Monday 2 February 1970. The young man Edith refers to must be Frank Hempl.21It was Hempl who reported Russell’s death: he is noted as being present at the death. The death certificate, 3 February, lists uremia and bronchial pneumonia as the causes of death. Edith wrote an “X” on that page of her pocket diary. In the years to follow she also recorded the time, 6 pm.

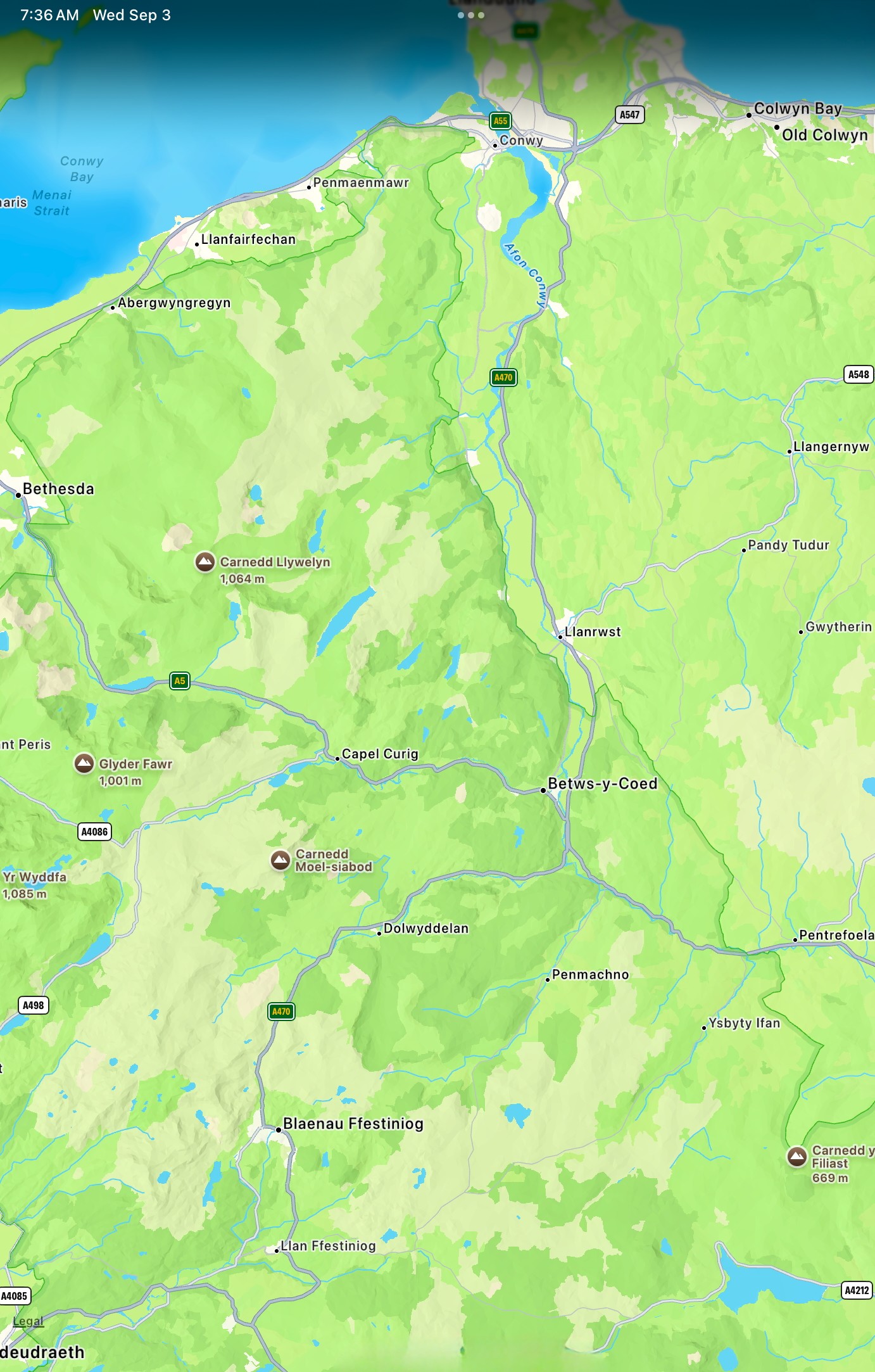

Barry Feinberg recounted: “I was woken at 4 on an icy winter morning by Anton Felton telling me the sad news and arranging to pick me up immediately … We arrived about five hours later to find the house already under siege by the world media. Part of our task was to reinforce the small guard of Russell’s assistants who were protecting Edith from the swarms of news-people … Later, a little after the undertakers had arrived, I had a private moment to pay my respects….” (p. 77). They did not stay for the cremation. Russell was cremated on 5 February at Colwyn Bay, Rhos-on-Sea, Conwy. Tom Jones & Son were the local undertakers, builders and plumbers. Ken Coates, a Peace Foundation director, wrote to them on 3 February confirming their conversation of 2 February. He noted Russell’s instructions: “I wish my body to be cremated and my ashes to be scattered and I wish to have no funeral ceremony whatsoever.” The crematorium rooms were to be closed to the public and the press, the coffin was not to be displayed, there was to be no music or flowers. “If there are cars waiting when you should leave the hospital, we should like you to avoid becoming involved in a procession.”22The route, on A470, would have taken the coffin past Llan Ffestiniog where Russell had lived in the late 1940s and onwards past Llanwrst before turning right to Colwyn Bay. I travelled part of this route in August 2025.

Trevor Fishlock described the events in The Times on 6 February. Russell’s “unadorned oak coffin, in a small, humble hearse” arrived first. “Four of the undertaker’s men lifted the coffin out and a fifth man stepped forward to help to carry it” inside. The fifth man was Brendan Lynch, an Irishman who had travelled from London to honour Russell. Lynch had been active with the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament in 1964. There were about 20 people present, standing “by the trees, well back, not wishing to intrude”. Presumably members of the press formed part of this group. “After a few minutes Lady Russell arrived in a taxi.” She was accompanied by Conrad and his wife Elizabeth, Christopher Farley and Ken Coates. “The doors were closed and for a minute or two the small party stood silently in the green and white chapel … Then the coffin slowly moved from their view. The homage was over and they emerged and drove off at once.” The final resting place for the ashes was to be decided later. Lord Russell had not wanted flowers: but a bunch of daffodils and irises arrived at the crematorium anonymously with the message ‘In affectionate remembrance’.” According to the Daily Telegraph the coffin arrived shortly before 1 pm … three senior police officers saluted as the hearse drew up. Russell’s ashes were to be stored until further direction according to J.W. Barker, Director of Parks for Colwyn Bay. Ray Monk wrote that “afterwards his ashes were scattered over the Welsh hills” (p. 500).

Two of her step-children paid tribute to Edith. On 15 February Conrad wrote: “I’d like to say, too, how much pleasure it gave me to see him so happy with you. I think you made him much happier than he had ever been before … I hope you know how much joy the past two and a half years have been to me, and how grateful I am, both to my father and to you, that they were possible.” On 27 March Kate wrote: “I think the knowledge of all you gave him & of its immense value to him can at least make you stand up straight & feel proud.”

Edith stayed on at Plas Penrhyn. In March 1970 she went ahead with the plans to construct a maisonette, presumably with the same plans as had been abandoned in 1960. A new bathroom was added. In August 1970 the gardener Thomas W. Mullock and his family moved into the maisonette. Mullock had been the gardener since 1961. In November her domestic staff had to be let go to save money but Mullock was kept on. He died in 1973 and a new gardener, Piers Forestier-Walker, was hired. Peanut, the dog, died on 28 October 1975 following surgery in May. Piers left at the end of October that year. Flooding in December 1974 caused damage to both Anne and Lucy’s bedrooms. A contractor took ten days to repair the damage in January.

The last decade of her life was not an easy one for Edith. It took years for the Estate to be settled and money was tight. Conrad and his family wanted to come for Christmas in 1970 and Edith had to say no because she had no cook. Less than a year before she died this exchange took place: Christopher Farley to Edith’s lawyer, Jack Black, 5 February 1977: The Estate “has now entered its eighth year without settlement … [the] strain for Lady Russell in not knowing her real financial circumstances … must be very considerable … It really is very worrying that she continues to live alone and has no idea if and when she may be able to afford to have someone live in to help with some of the essential housework.” Black replied on 8 February: “I am very sorry that Lady Russell should find herself in this uncertain state for so long. The matter is by no means neglected and I will do whatever is possible in these almost Dickensian proceedings to bring things” to a conclusion. “In the meantime I think the executors should certainly consider getting someone to live in to help Lady Russell.”

Conrad, his wife Elizabeth, and their children often came to visit; a second son, John, was born in November 1971. In July 1972 visitors included Russell’s cousin Margaret Lloyd and other family members. Kate Tait arrived for the first weekend in August. Ronald Clark visited in April 1972 and returned in December. In February 1973 he returned alone and then with John G. Slater on 13 May 1973. Old friend Peggy Kiskadden visited several times. She came for a few days in May 1973, returning in August 1975, September 1976 and May 1977. Other 1973 visitors included Ivor and Enid Grattan-Guinness in March followed by the Flexners in August. Ronald Clark returned twice in 1974. Brian McGuiness who wanted to see the Wittgenstein books in Russell’s Library also visited in 1974. Lester Dennon and his wife stayed at Portmeirion for a few days in August 1974. Visitors in 1975 included Graham Whettam and his wife, David Wood, and Elias Bredsdorff and his wife. In June 1976 Barbara Strachey Halpern came to tea. Jo Vellacott and Elisabeth Eames both visited separately in June 1977. Edith provided tea and possibly the occasional meal but all visitors stayed at Portmeirion. On 13 June 1977 Edith noted in her pocket diary that her friends and neighbours Rupert and Elizabeth Crawshay-Williams killed themselves. Her pocket diary mainly recorded appointments but on 3 Oct. 1974 she noted: “Beset by birds! Wren in kitchen. Chaffinch in Sitting-Room. Robin in dining room.”

There were visits from the three step-granddaughters she had helped to raise. Anne’s visits came to an end once she moved to America c.1974. Lucy killed herself in 1975. Sarah’s last visit was in the summer of 1977. Edith maintained a friendship with her neighbours Michael and Mary Burn. Mary died in 1974. Edith devoted herself to the Peace Foundation in her role as the Honorary Vice-President. She was in frequent contact with the directors and secretary and wrote many letters asking others to support the Foundation. She died on 1 January 1978. Christopher Farley had been visiting. Throughout her widowhood he visited her several times a year.

The Russell Archives were offered furniture from Russell’s sitting room at Plas Penrhyn on 14 March 1978. A description was sent of the items, now on display in Russell House. They included “[a] drop leaf mahogany side table (which BR used to serve tea) … [a] two-level table, with drawer under (which BR used for his personal effects ... [an] oak footstool (which BR used for his books of the day)” as well as a winged chair, a revolving bookcase, a writing desk and chair (Rec. Acq. 1283). Various smaller personal effects from this room were also offered and purchased. The lamp on the desk is one of a pair—both Edith and Russell had matching lamps on their desks. Pictures of both desks were taken by David Lewis-Hogdson.23

Russell House, McMaster, display room

The Welsh politician and Labour MP, Leo Abse,24visited Portmeirion after Edith’s death. He also gained access to the nearby half-empty Plas Penrhyn. “Most of the ungainly furniture had gone, some across the Atlantic for the re-creation, over the ocean, of his study, as an ugly shrine for his admirers … The shabby buff-coloured walls still had hanging upon them the vulgar embroidered tributes, gifts from Mao and from Ho Chi Minh: the cold linoleum-floored bathroom still had as its centrepiece a stained, chipped, enamelled tub. Only a reproduction of Piero della Francesca’s peaceful Holy Ghost, remaining in its position above the bed of the avowedly godless guru, strove to overcome the cheerlessness.” Carl Spadoni chose to quote from Abse’s article, “The Italian Job?” in his article, “Bertrand Russell on Aesthetics”. Spadoni does not name Abse, instead describing him as an admirer of Russell. Larry D. Harwood then picked up on what Spadoni had quoted but in his hands the single visitor has become the many who visited while Russell was alive: “Visitors to Russell’s beloved home in Wales, Plas Penrhyn, frequently commented on the plainness of the rooms. That is, decorations seemed minimal and the room dominated by dullness” (p. 272). Harwood lists his source for this as Spadoni and in his footnote quotes from Spadoni who in turn was quoting from Abse.

Several people associated with the Russell Archives and the Centre have visited Plas Penrhyn. Ken Blackwell, of course, was there organizing papers and making a listing of the library while Russell was still alive. He returned with his family in April 1977 staying in Portmeirion. Judy Bourke could not find the house in 1990 but managed to find it in 1993. It was neglected and being used as an art school. Despite the deep grass and shrubbery she took three photographs, which appear in her article in the Russell Journal. She was not able to go inside.

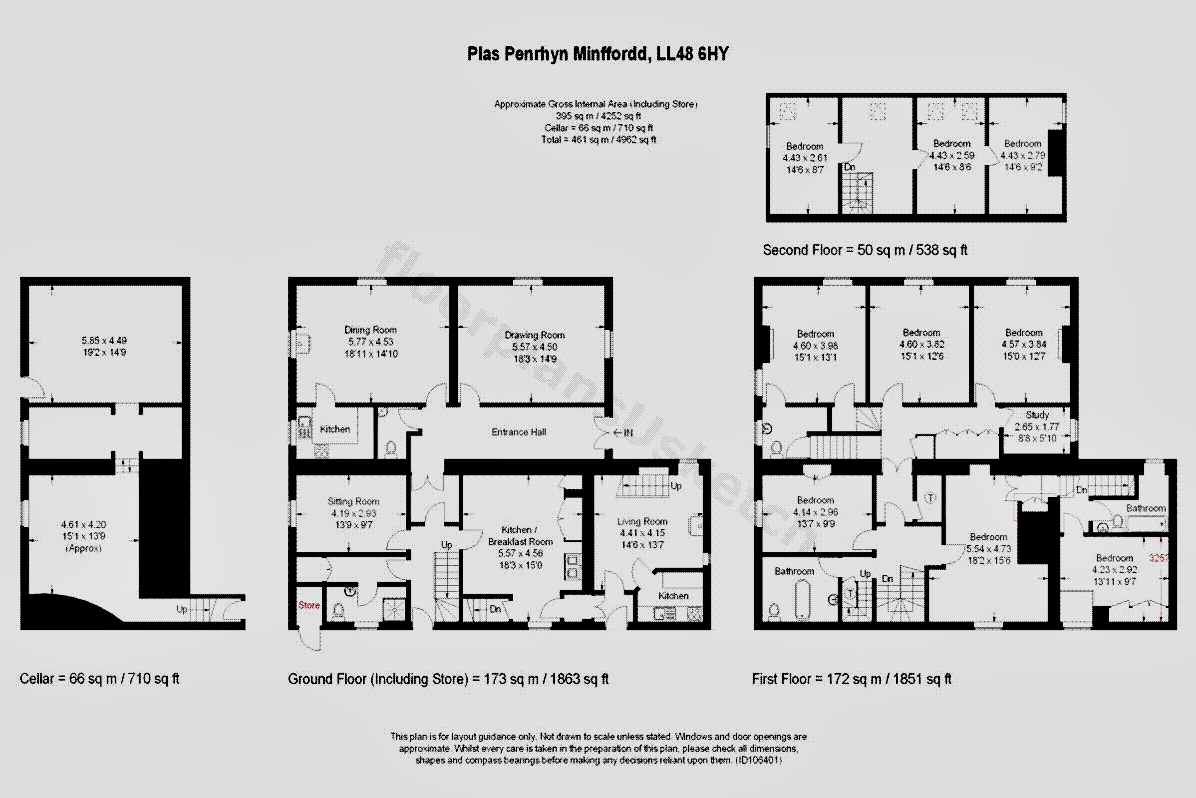

When the house was put up for sale in June 2014.25The estate agents, Tom Parry & Co., described the house as being built “in the late 17th century/early 18th century [with] the Regency north west wing built in the 1800s.” The Regency wing contained the following: on the ground floor an open porch, principal hall, cloak room, drawing room, dining room and kitchen; on the first floor a landing, 3 front bedrooms, bathroom, study. The rear wing contained a rear hall, inner cloaks area, sitting room, inner lobby, shower room, kitchen/breakfast room. On the first floor a landing, 2 bedrooms and bathroom. On the second floor a landing and two attic bedrooms. The north east wing had an entrance hall, living room and kitchenette on the ground floor. The first floor had a landing, a bedroom with limited headroom and a bathroom. Outside: there was “a fine full length Regency verandah and slate flagged terrace to the front … a lean-to greenhouse to the side [and a] cellar with slate slab flooring housing” the central heating boiler. Notable features include a “late Victorian geometric tiled floor” in the principal hall and painted slate fireplaces in two rooms in the Regency Wing. The Epstein bust had been located at the end of this hall.

Floor Plan

Andrew Bone visited Plas Penrhyn in July 2018 and wrote down a few thoughts about his visit. He “managed to locate Plas Penrhyn, which is on a rise up the narrowest of unmarked country roads. I instantly recognized the veranda and spectacular view from a number of different Bertie pics. I peered into a couple of windows near the front/side door and the place appeared uninhabited. But there were definitely signs of life on the other side of the building, so I rang the bell and was greeted by Ed Cohen, a Rutgers philosopher. I explained my BR affiliations and he kindly invited me inside for a quick tour, which was an unexpected bonus. Ed was staying there for a week as the guest of the current occupant (a writer perhaps, I didn’t catch his name), but the house has been purchased by a London architect: so who knows what fate awaits it. The interior was in a distinctly mixed state of repair, with several rooms clearly uninhabited. But I suspect that the layout largely reflects BR's lived experience in PP. (A partition to create a holiday rental on one side of the property had been removed.)” Andy took several photographs, one of which appears below.

Verandah with estuary

The current state of the house and its owner remains a mystery. I wrote a snail mail letter to the house occupant but received no reply. The most recent photographs are those that appear on the British Listed Building website. They were uploaded by Archie Harris in July 2020.

Russell was fortunate to spend his final years with a loving wife, reunited with his son who visited frequently. He had grown up in Pembroke Lodge, a house with sweeping views, surrounded by gardens. After a life punctuated by many moves, he found a home that echoed those attributes of Pembroke Lodge. It was a place that he could feel truly at home.

Russell on verandah

The portrait of Russell in Additional Photographs is reproduced courtesy of the National Library of Wales.

© Sheila Turcon, 2025

Sources

Leo Abse, “The Italian Job?”, In Britian (Oct. 1978: 26-9).

Judy Bourke, “The Search for Plas Penrhyn”, Russell: The Journal of the Bertrand Russell Archives n.s. 14 (Winter 1994-95): 173-7.

Yuen Ren Chao, “With Bertrand Russell in China”, Russell: The Journal of the Bertrand Russell Archives o.s. no. 7 (Autumn 1972): 14-17.

Ronald W. Clark, The Life of Bertrand Russell. London: Jonathan Cape and Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1975.

Rupert Crawshay-Williams, Russell Remembered. London: Oxford U.P., 1970.

Mansel Davies, “CND, Pugwash, and Eddington”, Russell: The Journal of the Bertrand Russell Archives n.s. 11 (Winter 1991-92): 193-9.

Barry Feinberg, Time to Tell: An Activist’s Story. Newton, South Africa: STE, 2009.

Trevor Fishlock, “Brief and Silent Farewell to Philosopher of the Age”, The Times, 6 Feb. 1970, p. 7.

Larry D. Harwood, Mad About Belief: Religion in the Life and Thought of Bertrand Russell. Eugene, Oregon: Pickwick, 2024.

David Horowitz, Radical Son: A Generational Odyssey. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1998.

Desmond King-Hele, “A Discussion with Bertrand Russell at Plas Penrhyn, 4 August 1968”, Russell: The Journal of the Bertrand Russell Archives 16 (Winter 1974-75): 21-6; includes a Plas Penrhyn map.

John R. Lenz, “Bertrand Russell and the Post-War Greek Left”, Bertrand Russell Society Bulletin no. 158 (Autumn 2018): 32-7.

Ray Monk, Bertrand Russell 1921-70 The Ghost of Madness. London: Jonathan Cape, 2000.

“Morning to Remember”, South Wales Echo, 5 Feb. 1970; clipping in RA.

Caroline Moorehead, Bertrand Russell: A Life. London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1992.

“No Fuss at Ld Russell’s Cremation”,Daily Telegraph, 6 Feb. 1970, p. 19.

Bertrand Russell, The Autobiography of Bertrand Russell 1944-1967, volume 3. London: Allen & Unwin, 1969.

Conrad Russell, “My Father Bertrand Russell”, Illustrated London News, 14 February 1970, p. 13.

Carl Spadoni, “Bertrand Russell on Aesthetics”, Russell: The Journal of the Bertrand Russell Archives 4, no. 1 (Summer 1984): 49-82; at 76.

Katharine Tait, My Father Bertrand Russell. New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, 1975.

Archival correspondence: Chamberlaine Bros., Frances Williams, Percy A. Popkin, Rupert and Elisabeth Crawshay-Williams, Elizabeth Trevelyan, Frances and Learned Hand, Osmond Williams, Lewis Casson, Nell Morgan, Mrs. Humphreys, Conrad and Elizabeth Russell, Christopher Farley, Ken Coates, Y.R. Chao, Brand Blanshard, Victor Purcell, Helen Hervey, Miriam Reichel, Zora Lasch.

Internet Sources

British Listed Building

Cadw Listed Building

Plas Tan-Yr-Allt Country House and Estate

- 1

They were mainly at Deudraeth Castle hotel (now known as Deudraeth Castell) with short intervals at its sister hotel, the Hotel Portmeirion.

- 2

Williams had worked for him at his home in Llan Ffestiniog.

- 3

In 1972 its name was changed to the Welsh spelling, Porthmadog.

- 4

Williams (1914-2012) was the grandson of Sir Arthur Osmond Williams (1849-1927), an uncle of Clough Williams-Ellis (1883-1978).

- 5

Edith told Elizabeth Trevelyan that Russell needed rest and they planned on being in Scotland “from mid-May till mid-June” (30 April 1955).

- 6

Russell’s grandchildren, Anne, Sarah and Lucy, abandoned by their parents, John and Susan.

- 7

The tenant’s name was William Kitching. He sent Edith a listing on 15 June 1955 which she annotated, noting the things that she did not want.

- 8

Not a valley but the Glaslyn estuary.

- 9

Letter from Osmond Williams, 13 June 1955, confirms the Shelley quotation. Russell did publish “The Importance of Shelley”, London Calling, no. 905 (14 March 1957): 10 (B&R C57.06) and 16a in Papers 29.

- 10

Williams-Ellis family, Clark, p. 551; Cooper-Willis family, Monk, p. 390.

- 11

Alys Russell lived in St. Leonard’s Terrance in the 1920s according to Alan Wood, p. 143.

- 12

29 May 1962 to grand-daughters Sarah and Lucy. Christopher Farley explained in a 1963 note (document .053080) that “Peanut was named after [Hugh] Gaitskell’s attack on unilateralists, who—he said—had not the brains of a peanut.” Hugh Gaitskell (1906-1963) was the leader of the Labour Party; unilateralists wanted unilateral nuclear disarmament, which Gaitskell opposed. I could not locate a source for Farley’s quotation. Another explanation is that Gaitskell called hecklers at a May Day Rally in Glasgow in 1962 “pro-Soviet peanuts” (the peanutsclub.blogspot.com). He spoke in favour of the Polaris nuclear missile system.

- 13

Letter from Deudraeth Rural District Council, 1 June 1956.

- 14

Edith to Mr. Williams, 18 June 1956.

- 15

A maisonette consists of living accommodation of two stories in a larger building with a separate outside entrance.

- 16

“Earl Russell”, The Times, 10 Feb. 1970, p. 12

- 17

The relevant correspondence: Elizabeth and Rupert Crawshay-Williams and the Deudraeth Rural District Council (18, 26 May 1956, document .3100256, Rec. Acq. 501E

- 18

This quotation appears in John R. Lenz’s article.

- 19

Kenneth Blackwell tells me that Ralph did not stay at Plas Penrhyn but had a cottage in the village of Penrhyndeudraeth. Blackwell stayed in a nearby B&B when he was there from late July to mid-August, 1966.

- 20

David, Anne, and Jonathan. She would later have two more children.

- 21

Hempl was not a paid member of staff. He was described by Elizabeth Russell, 31 March 1969, as being in the service of the Russells. He was left a small gift of £50 pounds by Edith providing he was still living at Plas Penrhyn; letter from Jack Black, 27 April 1970.

- 22

Presumably Bron Y Garth hospital which closed in 2009.

- 23

Rec. Acq. 1774; images collected by Ken Blackwell. Hodgson must have sold them to Mary Evans Picture Library where they are now available for purchase.

- 24

Apse had met Russell during the Cuban missile crisis of 1962.

- 25

It was sold in April 2015. I do not know if Plas Penrhyn was sold during the time after Edith died and before this sale took place. The Williams family has a long history in Wales and may have kept ownership until 2015 while continuing to rent it out. Osmond Williams did not die until December 2012.