By the time Russell and Dora returned from China, Dora was soon to enter the third trimester of her pregnancy. The need to get settled quickly was urgent. They first stayed in the Battersea flat he had shared with Clifford Allen. He wrote to Ottoline on 26 August: “We are here for about a week, and then probably go to the country.” Clifford Allen had “met us at Euston [station] on arrival—we had telegraphed to say we were going to a hotel, but he was all kindness and urged us to go to his flat. We understood he was lending it, but when we left he presented us a bill which was nearly as much as we should have paid at a hotel…” (13 Sept.). In the same letter to Ottoline he told her that Allen had “said he was thinking of giving up his flat, and would let it to us, certainly for the confinement and probably permanently. So we ceased to look about. At the last moment, just before we had been going to leave London, he announced he had changed his mind.…”

It was C.P. Sanger who was supposed to find them a cottage in the country at “no more than 2 guineas a week … He left the business to Miss Wrinch,1who had a cottage of her own to let at 4 guineas, and had nothing else to offer us. There seemed some difficulty about service, but she said she had arranged it. Now, however the food is not good enough to keep Dora in health, and we have to hunt desperately for a cook … If we can’t get a cook, we can’t stay here” (13 Sept. to Ottoline). On 26th of August he had asked Ottoline for help in finding a cook.

Wrinch’s cottage was in Winchelsea, Sussex. Dora remembered that it was thatched, “on the edge of the marshes … which Dot Wrinch rented and had generously vacated for us” (Tamarisk Tree, p. 147). On 7 September Russell wrote to Ottoline from Strand cottage: “We came here the day before yesterday … It is a nice cottage, charmingly furnished, with several spare rooms.” After his concerns expressed in his letter of 13 September, Russell told Ottoline on the 18th of September: “We have got another servant here now and are quite all right … I expect Dora will go to her people for her confinement,2and meanwhile I will hunt for a flat to go to when she is well.” I wonder as Russell spent time in Winchelsea if he reflected back upon the cottage, to be lent by the Rinder family, where he was going to stay with Colette (Constance Malleson) after he left Brixton prison in 1918. Alas, this never happened because of his jealousy. My guess is that he never gave it a second thought. He and Colette did stay in nearby Rye upon his return from Russia in 1920. She remembered: “I feel you still beside me, I see your hair glinting against the Winchelsea sky” (17 July).

Dorothy Wrinch

While at the cottage, Russell’s divorce from Alys was finalized. He told Ottoline on 26 September: “The decree was made absolute last Wednesday … Dora and I are going to be married tomorrow.” They married at the Battersea Registry Office3on 27 September. Dora described the wedding: “one day, we came up to a registry office in Battersea, myself now rather large in a black cloak, and, with Bertie’s brother Frank and Eileen Power4for witnesses, we were married…. I had a bunch of sweet peas I had picked and wrapped in a newspaper, which they maintained was my bridal bouquet. The Registrar wished Bertie ‘a happier experience’ and we all went and had tea at a local café” (Tree, p. 149). Russell’s account of their wedding takes up one sentence in his Autobiography (2: 136). Frank’s estranged wife Elizabeth5wrote to Russell telling him she wished she could have been at the wedding (n.d., document .055289). On 5 October she told Russell that she would pay for a dinner service, already selected by Russell, as a wedding gift.

Regarding their search for a home Russell wrote: “I tried to rent a flat, but I was both politically and morally undesirable, and landlords refused to have me as a tenant” (Auto 2: 151). Dora also remembered that the refusal was “politically motivated” (Tree, p. 147). Allen’s flat (for a time shared with Russell) was no. 70 in Overstrand Mansions, Battersea; because of Allen’s change of heart they then settled on a flat “on the staircase next to Allen’s, very nice in every way; the existing tenant wanted to let us the rest of his lease, and we would then have got a new lease from the landlord” (to Ottoline, 13 Sept.) No. 55 was a three-bedroom, two bathroom flat on the top floor of Overstrand Mansions with beautiful views of the park. Now a freehold flat, it last sold in 2006 for £675,000.

The flat was rented by J.B. Hill who was going to sublet it to the Russells. The agent, acting on Hill’s behalf, was Frederick W. Coy, a chartered surveyor, located at 191A Battersea Bridge Road. On 3 September Russell wrote to Coy agreeing to take over the tenancy until March 1923 for £86 per annum, agreeing to purchase the furniture and effects for £225, and also agreeing “to carry out any necessary decoration at my own cost.” Russell put down a deposit of £22.10.0. On 9 September, Coy sent a telegram to Russell telling him that the licence to assign no. 55 had been refused. It turned out that Harry Chester of Ranken Ford & Chester, 4 South Square, Gray’s Inn was the culprit. Why this barrister had the power to refuse the licence is not known. He may have been representing the building owner whose name was never mentioned. On 24 September Russell wrote to Chester that he was very anxious to obtain the flat and would not use it for political purposes. He had not been active politically for 3 ½ years. Russell also proposed that he would pay to have electric light added to the flat; presumably it had gas lighting at that time. In reply Harry Chester wrote on 30 September that he would accept Russell as a tenant provided that he would be a “responsible, respectable and desirable tenant” who would “not use the flat for any purpose which would cause any annoyance or inconvenience to the other tenants of the property.” He offered Russell only a one-year lease at £100 “from Michaelmas last”, noting that Mr. Hill had not been paying fair market value for the flat. He also wanted further references, even though Russell had given full references to Mr. Coy. In reply, Russell on 1 October noted that he could not redecorate the flat6and put in electric light when he was only being offered a one-year lease. He thus refused Chester’s begrudging offer. Chester snipingly replied on 3 October: “I have done my best to meet your views, but apparently the terms are not acceptable and I assume you will not wish to proceed with the proposed agreement.” Mr. Coy got back in touch with Russell on 14 October offering him “a little flat in Albany Mansions of two bedrooms, and one sitting room … for the next twelve months.” The rent was only “£50 per annum” because of the short lease length. This offer was too little, too late.

Time was of the essence. Russell needed to switch gears and buy. He found a freehold townhouse, 31 Sydney Street, in the borough of Kensington and Chelsea, owned by Mrs. Frances Thornton. This was a return to the neighbourhood where Russell and Alys had rented flats at the turn of the century. Russell is more closely associated with Bloomsbury and that is where his English Heritage blue plaque is located. However, Carla Passino writing in Country Life made an argument for Chelsea: “… the man that most marked 20th century Chelsea was perhaps Bertrand Russell, who first moved there in 1902 and kept leaving and returning for much of his life. In 1923, he decided to run for Parliament as a Labour candidate, despite George Bernard Shaw’s advice not to waste any money on a place ‘where no Progressive has a dog’s chance.’” Passino noted that The Principles of Mathematics “opened the way for Russell to become modern Britain’s greatest philosopher—and sealed old Chelsea’s place in the country’s intellectual firmament” (p. 52). Dora found “Chelsea was a most agreeable place to live; the King’s Road7was not then garish, but an ordinary, good shopping street …” (Tree, p. 152).

The property had three floors and a basement.8On 5 October, the Russell brothers’ lawyer John J. Withers, from the legal firm of Withers, Bensons, Currie, Williams, wrote to Russell, agreeing “to act in the matter of the purchase” of this property for £1,800. “I think we shall find no difficulty in finding the purchase money pending the variation of the settlement.”9The following day S.F. Hayward, Manager, Estate Agency Department at Peter Jones sent Russell a receipt for £180, a deposit on the purchase of Sydney Street; the firm held the property “as stakeholders pending completion …” A delay in the purchase of Sydney Street was caused by the fact that the deed was missing. Withers informed Russell of this development on the 10th of October; the letter also contained information on financing. On 12 October Russell wrote Ottoline: “We are again homeless. The one we agreed to buy turns out to have a bad title. It is miserable.…” On 15 October Withers wrote: “I do not think there is much doubt than an absolute title will be granted [to Mrs. Thornton].” She had moved out to Artillery Mansions by 20 October Withers informed Russell. The Russells took possession on the 21st, the day their furniture arrived. Withers wrote on that day that Mrs. Thornton’s lawyers “have received official intimation from the Land Registry that subject to the usual formal requirements of the department, which includes a month’s notice which will be inserted in today’s issue of the London Gazette, an absolute title to the property will be registered.” The actual purchase was not completed until 7 December 1921 when Withers informed Russell that he had “lodged the Land Certificate at the Land Registry in order that you may be registered as the proprietor of the property.”

Withers noted on 30 January 1922 with regard to insurance: “The Policy provides that no article (furniture, pianos, and organs excepted) shall be deemed of greater value than Five per cent of the full value of the contents (£2000) unless such article is specially insured in a separate item; and the total value of gold and silver articles jewellery and furs shall be deemed not to exceed one-third of the full value of the contents unless specially agreed. The gold medal (£100),10the Chinese picture (£200) and the silk and ermine cloak (£150) appear to be the only articles which need to be specially mentioned in the Policy. You give the total value of these articles mentioned in your letter as £700, and this leaves only £1300 for the insurance of the remainder of the contents.” Withers wanted confirmation that this would be adequate.

Russell described moving day to Ottoline in his letter of 28 October: “All day Friday vans kept coming with furniture from Cambridge, from [Clifford] Allen’s, from Dora’s flat [in Bloomsbury]. Books poured in in such multitudes that it seemed as if there would never be room for us too. Wittgenstein’s dining table was so vast that it couldn’t be got into any room except the basement, and that only by taking out the window, so our dining-room has to be in the basement. We moved in ourselves on Monday, and now all is straight except the ground floor, where shelves have to be made for books.” Dora wrote that the house “acquired a certain distinction by the odd bow window jutting out, as from a medieval castle, from the ground floor front. This was to be Bertie’s study and presently he was to be seen, day after day, framed by this window, sitting so quietly at a small table, turning over page after page of neatly written manuscript” (Tree, p. 150). In 1923 Russell placed a gift from Ottoline on the Chinese table in the drawing-room (letter to her of 3 Jan.).

Mrs. Thornton wrote to Dora on 6 October that “Turner is the best and earliest news agent round here—he is in Sydney Street, nearer to the King’s Road than this house.” Also, her cook, Mrs. Knight who lived in Pimlico, would be pleased to stay on. Something went wrong with this arrangement. On 19 November 1921 a member of Dora’s family, possibly her sister Bindy, interviewed a cook “at the Registry Office in the Fulham Road … She will come in the morning about 7.30 in time to get breakfast at 8.30.” If Dora approved, the appointment of the new cook would be finalized on Monday, 21 November.

Caroline Moorhead wrote: “The Russells were living in a part of London he particularly liked with the Sangers11just around the corner in Oakley Street” (p. 338). Virginia Woolf wrote in her diary about a dinner party held there on 3 December 1921. Neither Dora nor Woolf’s husband Leonard attended. The dinner guests were all friends: Maurice Sheldon Amos and his sister Bonté; Rosalind Toynbee, the daughter of Gilbert Murray; and Helen Mary Lucas, another neighbour. Russell told Virginia: “I shall write no more mathematics. Perhaps I shall write philosophy … I have to make money” (Diary, pp. 146–8). In addition to those already mentioned, Dora listed others in the neighbourhood with whom they socialized: Sybil Thorndike, the actress, and her husband Lewis Casson, Desmond MacCarthy, A.N. and Evelyn Whitehead as well as their son North and his wife whose child attended John’s first birthday party (Tree, p. 152). Visitors included Arthur Waley, W.B Yeats and T.S. Eliot. “Harold and Frida Laski were not far away and frequent visitors. Ottoline Morrell came too, in her taffeta and pearls” (Tree, p. 153). “Among the Bloomsburies I liked best was Leonard Woolf, who came quite often to Sydney Street” (Tree, p. 155).

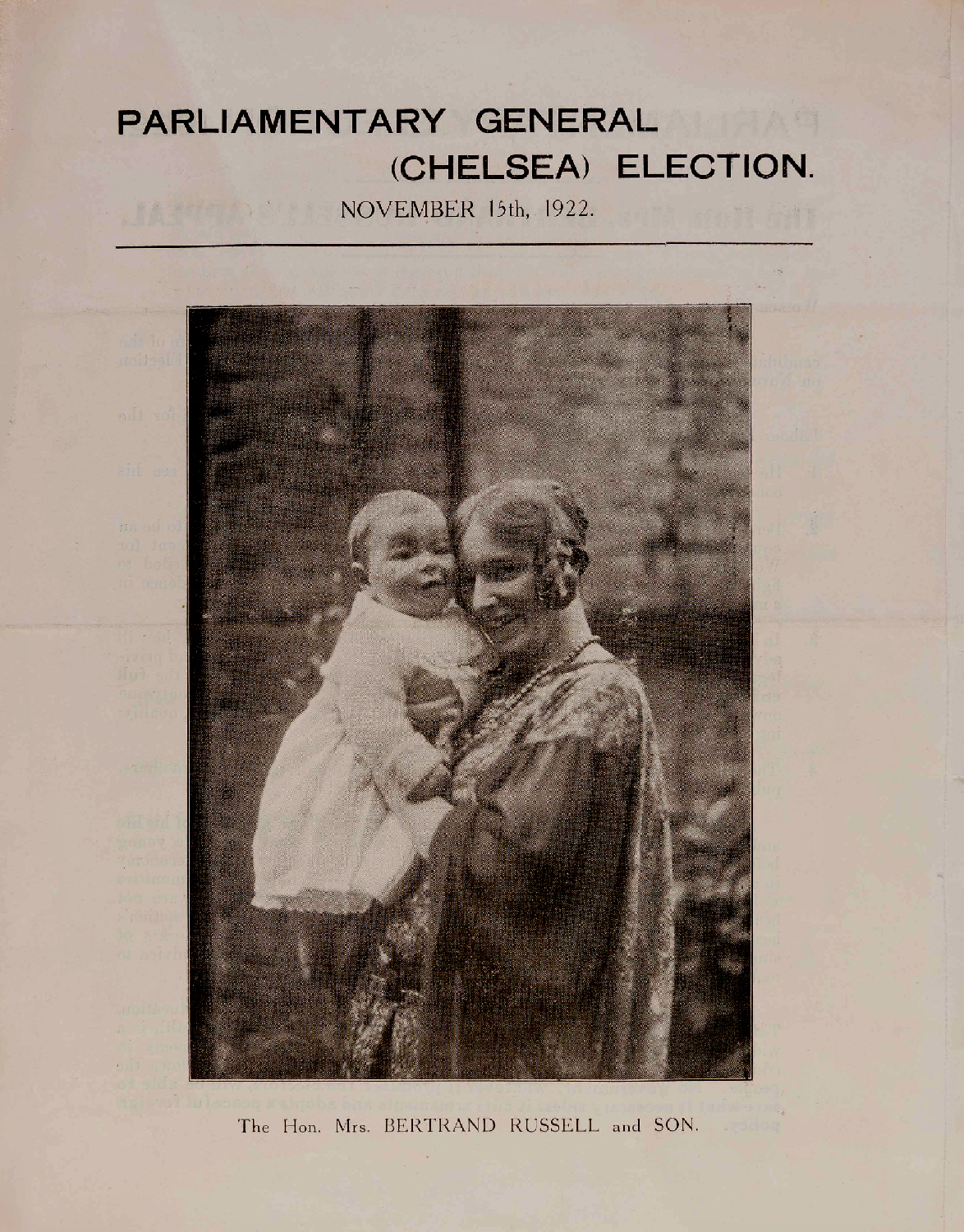

Russell’s sister-in-law, Elizabeth, who maintained friendly relations with her brother-in-law and his new wife, was an early visitor. Ronald Clark quoted from her letter to Katherine Mansfield, 7 November 1921: “I’ve seen Bertie several times & his round, little wife, & their snug & happy house in Chelsea … with Bertie looking perfectly blissful” (Clark, p. 418). They had achieved their goal of finding a home for the child to be born. “Neither Bertie nor I knew what to do about doctor and nurse for the confinement. His sister-in-law … Elizabeth Russell, came to our rescue. Her brother Sir Sydney Beauchamp was a first-class gynaecologist, and Elizabeth insisted that no one but he should take the case. After examining me, and bearing in mind what this birth meant to Bertie in his anxious and delicate state, he decided to induce the child about a month early. Even so, it was a forceps delivery, and I think that John did not do well out of the bargain. As I lay there on the top floor on 16 November 1921 in the bed that had been Wittgenstein’s, giving birth, the bells of St. Luke’s church at the end of the street were ringing in practice, but to me at that moment they rang for my son … Elizabeth came to cheer and entertain me … One day only Bertie’s physician Dr Streatfeild came [followed by] the gynaecologist Mr. A.H. Richardson [and] they had to break it to me that Sir Sydney had been knocked down by a bus and instantly killed. At such times one stupidly thinks of omens: John’s father had nearly died when he was conceived, and now his birth was shadowed by a death” (Tree, p. 151). To modern eyes, it is shocking that Russell’s needs would have been placed before mother and child.12

Dora with baby John

Dora related her daughter Kate’s birth with a single sentence: “My Kate, with great sense, bided her time, let us have a peaceful Christmas and appeared on 29 December [1923]” (Tree, p. 168). She was delivered by Mr. Richardson. Russell wrote of the births: “When my first child was born, in November 1921, I felt an immense release of pent-up emotion, and during the next ten years my main purposes were parental” (Auto 2: 150). During John’s birth, he “wrote an article on Chinese pleasure in fireworks, although concentration on so remote a topic was difficult in the circumstances” (Auto 2: 152). To Ottoline he mentioned nothing about fireworks; instead he wrote: “Her pains began about 5 last night and the child was born about 7 this morning … The Doctor and I sat up all night, gossiping and talking of carefully irrelevant topics” (16 Nov.). He noted that both of his older children were born at 31 Sydney Street (Auto 2: 151). About Kate’s birth Russell informed Ottoline on 31 December that the “child was born Saturday night, quite successfully—a girl, which is what we hoped. Dora is very well, and didn’t have a very bad time. The child is fat and large—weighed 8 lbs 6 oz and seems very healthy.”

Although Kate left Sydney street when she was only three years old, she retained some memories. It “was full of beautiful things my parents had brought home from their travels … and served as a center for their ceaseless activity in politics … All my memories of the London house are dark—dark wood, dark halls, firelight on the ceiling, fog in the streets … My mother and father, however, enjoyed their London life, and they valued the intellectual benefits of an urban environment for the children … We learned much … from the immense wealth of museums and monuments … John could enjoy the companionship of children his own age. He went to a Montessori nursery school….” Kate also related one terrifying encounter she had with Sidney Webb in a dark hallway when he asked for her eyes (My Father, pp. 8–9).

John told Caroline Moorehead that “his earliest memory was of the basement dining room … where the family had breakfast together … His second memory was of walking [to school] with his father, over the river on a foggy morning with the mist rising from the water and the cab drivers shouting to their horses as they passed in the grey misty light. He would always remember the smell of the horses’ warm dung” (p. 360).

Russell had already decided when he was in China to not return to Trinity, although he “had no obvious means of making money, and at first I suffered considerable anxiety” (Auto 2: 152). Just after John’s birth he gave three lectures in Manchester on “International Problems of the Far East”. The offer to give these lectures for £20 was received on 13 September from the Independent Labour Party. In March 1922 he gave the Conway Memorial Lecture at the South Place Institute, published as Free Thought and Official Propaganda. He and Dora collaborated on The Prospects of Industrial Civilization (1923). On 14 October 1925 he told Ottoline that he “had to finish a book on Education,13and then prepare masses of lectures….14In the autumn of 1926 he began to deliver “The Problems of Philosophy” in London for a second time to the British Institute for Philosophical Studies and added another series, “Mind and Matter.”15 He also returned to Cambridge in the autumn of 1926 to give the Tarner lectures, published as The Analysis of Matter (1927). On 2 February 1927 he told Ottoline: “I am immersed in Chinese affairs—every free evening this month I am speaking on China … Last night I went to hear a man named Rose, who was at the Legation in Peking when I was there….”

He achieved financial success through journalism and the writing of popular books, beginning with The A.B.C. of Atoms in 1923. Much of this writing was done in Cornwall where he lived for part of the year beginning in 1922. “In 1924 I earned a good deal by a lecture tour in America.16But I remained rather poor until the book on education in 1926”17(Auto 2: 152). His children drew him towards education as a subject worth exploring. Eventually his interest in education went further than writing books. He told Ottoline on 2 February 1927: “Our school project develops—we mean to start in September….” The school project would cause them to leave Sydney Street.

I must admit that I have never been interested enough to go to Sydney Street to photograph it as I have other properties featured in this series, although I have been to Chelsea to attend the famous Flower Show and drink Pimm’s No. 1 Cup. The house is just one in a terraced row of very similar homes. The illustration below is a photograph that appeared in The Tamarisk Tree, taken in front of the house; the bow window described by Dora in her book is not there.

Dora in the front right smiles at her husband in front of their Sydney Street home

Google Street View gives readers a better overall view of the home. It reveals a red-tiled stoop, a black door with a fan window, a white façade, probably stone, on the basement and ground floors with yellow brick on the floors above. The differences between the houses are slight. The stoops have different tiles. Window shapes vary on the ground floor. Some of the homes now have one more storey than their neighbours.

Entrance to 31 Sydney Street, 2025

The couple did use the house for political activities, thus saving the cost of renting campaign headquarters. Russell’s Central Committee Rooms were listed as 31 Sydney Street SW3, in the campaign leaflets he issued in 1922 and 1923 when he was running for Parliament for the Independent Labour Party. Dora ran in 1924, also from 31 Sydney Street. Chelsea is a Conservative riding. Both of them ran to highlight issues, not to win. They both had the same election agent, H.W. Talbot, 8 Tetcott Road, SW10. The exterior photograph pictured above is from Dora’s 1924 campaign. In the interior photograph below from Russell’s 1923 campaign, family portraits can be seen on the walls. These pictures had been displayed on the walls of his homes beginning with his first home as a married man, The Millhanger. Russell told Ottoline that “on polling-day, John unprompted, went up the Mayor of Chelsea and said ‘Vote for my Mummy’. The Mayor was very solemn, and replied without a smile, ‘Vote for a Red, NEVER!” (10 Nov. 1924). Dora was also photographed in the house by the London portrait studio Vaughan & Freeman. She is shown below writing at a table; on it a small portrait of Russell is displayed.

Campaign headquarters inside Sydney Street

Portrait of Dora inside Sydney Street

The Russells decided that London was not the best place for young children to thrive physically and beginning in 1922 they spent part of the year in a home they acquired in Cornwall. On 4 January 1926 he told Ottoline from Lynton in Devon: “We go home tomorrow. I wish we didn’t—I hate London more and more. There seems so much to do there, and all of it futile—mostly answering the telephone.”

While they were in Cornwall, Sydney Street was let. Wheeler Brothers were used as the agent. The property was first rented to a Mrs. Dick-Lauder. She agreed to rent the property for 11 weeks, at £5.15.6, according a statement dated 31 March 1922. This was not ideal; it would have been preferable to have one tenant for the summer of 1922. Wheeler Brothers noted on 27 June it was necessary to check the inventory when she left: “we enclose herewith a list of dilapidations accrued … She contends that some of these items were in their present state when her tenancy commenced …We understand that Mrs. Russell arranged with Mrs. Dick-Lauder that instead of requiring her to wash or clean the curtains she would make a charge for so doing. Mrs. Dick-Lauder only had the two cream net curtains in the drawing room washed. Please therefore let us know what charge we are to make.” An invoice of 28 March from W.J. Jealous, a firm that did repairs and was located in Battersea, indicated that they moved furniture from Russell Chambers18to Sydney Street, as well as repairing doors and a lock, and altering a bed.

The next tenant in 1922 was Courtney Pollock. He agreed to stay for 10 weeks, at 3 guineas per week. His first complaint contained in a letter to Russell from Wheeler Brothers of 16 June was that he needed four beds, rather than three beds and a divan. A follow-up letter of 27 June listed even more complaints. He didn’t want to pay for the rent of the gas stove. “He had not viewed the premises before taking them, and he now raises a number of matters which are not up to his expectations, the chief of which are as follows: a. There is no tea set or breakfast set … b. There is no crumb brush nor scoop. c. There are thousands of books and pamphlets exposed and about the rooms which he says are in his way … d. Every drawer in the writing desk is full with books, diaries, and papers which he says are in his way ... He complained about the rain coming through the skylight at the back of the hall and staircase.”

On 6 September 1922 Russell’s frustration with this tenant bubbled over in a letter to Gilbert Seldes: “(a) My tenants left the house so filthy it stank (b) They filled it with fleas (c) The slates came off the roof and the rain came in” (Papers 11: 202). It took a month to get the roof repaired. He told Ottoline on 3 September: “London is a beastly place and I hate coming back to it, particularly as we had filthy tenants who have made the whole house stink and spoilt many of our nice things. We have had to leave John Conrad in the country with his grandparents for a bit, as the house is not fit for his Lordship—(They had afflictions of the lungs and spat everywhere.)” The plan had been to rent out Carn Voel for August and September while the Russells were abroad. Ottoline invited them to Garsington.

In 1923 a Mr. E.R. Hulett stayed in the house. He had provided references from Central Estates Offices and C.E. Vaughan Williams, a solicitor; despite this he became delinquent in the rent. On the 10th of July Wheeler Brothers wrote: “we have called [at the house] three times, and also written to him once, but without result. This morning, however, he called to see us and said that he would let us have a cheque for the rent either tomorrow or the next day … Mr. Hulett mentioned that he has had considerable trouble with the drains, and has spent about £6 on them. This amount, he says, he will deduct from the rent.…” Russell told Ottoline on 17 July “My tenant in London got a month behind with his rent; after threatening to County Court I got the rent from a lady whose name was unknown to me. Probably she is the lady he introduced as his wife. I imagine she has taken up with another man, and my man sees no reason why he should go on paying for her. The lady I saw was a fascinating Creole (My tenant is from Havana) about whom any man might lose his head in 5 minutes.”

There is no further correspondence extant with Wheeler Brothers. It is not known if Russell continued to use the firm as agents, but the firm did draw up a Deed of Gift in 1926.

Roy Randall lived there in 1924 with other students. He wrote to Russell on 20 August, asking for an extension to the lease to the end of October, noting that “some of us have important final examinations” making “it an awful nuisance to have to contemplate moving.” He and his fellow tenants had all enjoyed using Russell’s library, unlike Mr. Pollock. Russell’s reply is not extant but this request was refused. On 10 October 1924 Dora wrote Russell who was still in Cornwall: “The tenants have moved things about so it is hard to find anything in a hurry. They will get out on Monday if they possibly can and are letting me go in to find things. I shall leave Bindy [her sister] to be mistress of the household and deal with minor things, keys lost, or repairs or anything. So far things look all right—the house is a bit untidy but not ill treated.” Randall was back in 1925. On 8 August 1925 he wrote to Russell trying to explain why a neighbour, Mr. Stokes, had complained about noise. The explanation was incoherent but Randall did promise to try “to prevent anything like it occurring again.” Randall would become Dora’s lover in 1927. He has faded into obscurity, not even mentioned in the Tamarisk Tree.

Russell had considerably more problems with his Sydney Street tenants than he had experienced with his tenants at Russell Chambers.

On 8 October 1926 the title to 31 Sydney Street was transferred to Dora; the document issued by the Land Registry Office noting this change is dated 27 November 1926. On 8th October a Deed of Gift19was drawn up by F.H.W. Wheeler, Chartered Surveyor, Wheeler Brothers. It noted a marriage settlement had not been created when Russell and Dora were married. Russell was now gifting Dora with “the furniture plate china glass pictures prints books musical instruments and household effects … at 31 Sydney Street … exclusive of moneys and securities for money letters manuscripts business books and accounts jewels trinkets and watches and articles of personal use or ornament.” It is possible this was done in anticipation of the sale of Sydney Street but there are no archival documents concerning its sale. Extensive electrical repairs and decorating took place in the autumn of 1926; a four-page invoice of 1 December 1926 from J. Davis, Builder & Decorator, for £82.9.0 was paid on 11 December 1926. Russell’s bank passbook indicates that 29 June 1927 was the last time the Chelsea Electricity bill was paid. The Russells left in 1927 to spend the spring and summer in Cornwall before moving to Telegraph House.

The townhouse at 31 Sydney Street20had served its purpose. It provided the couple with a home when they desperately needed one and a vibrant social life in town. Russell had lived in London since 1911. Upon return from China, he naturally returned to London. When he and Dora left London in 1927 to set up their school in the country, they found they couldn’t manage without a London pied-à-terre. Before long, they had leased a flat on Bernard Street in Bloomsbury, a neighbourhood where they had both previously lived.

© Sheila Turcon, 2021

Sources

Ronald Clark, The Life of Bertrand Russell. London: Jonathan Cape and Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1975.

Caroline Moorehead, Bertrand Russell: A Life. London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1992.

Carla Passino, “The Not So Wild West”, Country Life 216, no. 18 (5 May 2021): 50–2.

Bertrand Russell, The Autobiography of Bertrand Russell 1914–1944. Vol 2. London: Allen & Unwin, 1968.

Dora Russell, The Tamarisk Tree: My Quest for Liberty and Love. New York: Putnam, 1975.

John G. Slater, ed., Last Philosophical Testament, 1943–68, Vol. 11 of The Collected Papers of Bertrand Russell. London: Routledge, 1997.

Katharine Tait, My Father Bertrand Russell. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1977.

Virginia Woolf, The Diary of Virginia Woolf, ed. Anne Oliver Bell, Vol. 2. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1978.

Archival correspondence: Ottoline Morrell, John J. Withers, Crompton Llewelyn Davies, Frederick W. Coy, Harry Chester, Frances Thornton, Elizabeth Russell, Dora Russell, Gilbert Seldes, R.G. (Roy) Randall, Wheeler Brothers.

- 1Dorothy Wrinch, 1894–1976, a mathematician and former student of Russell’s.

- 2Russell had previously told Ottoline on 13 September that he didn’t think Dora’s family would take her if she remained unmarried.

- 3Presumably the registry office was in Battersea Town Hall. A heritage building, the Town Hall has now become an Arts Centre and can be rented out for weddings.

- 4Power (1889–1940) had accompanied them in Japan and on their trip home; Dora first met her at Girton.

- 5Elizabeth von Arnim (1861–1941), a novelist, was separated from Frank Russell. She maintained friendly relations with her brother-in-law and his new wife.

- 6He told Ottoline on 7 September that the flat “is very dilapidated and wants a lot done to it ….”

- 7Sydney Street runs between Fulham and King’s Roads.

- 8It now has four stories in the Google Street View image.

- 9His marriage settlement with his first wife Alys.

- 10Presumably the Butler medal.

- 11C.P. Sanger (1871–1930), one of Russell’s oldest friends, a barrister and fellow Apostle at Trinity and his wife Dora; Sanger wrote Russell on 16 September: “I feel so very much happier about your future now that I have seen you …”

- 12Dora’s due date was the end of November (Tree, p. 142).

- 13On Education, Especially in Early Childhood, begun in Cornwall and completed in London.

- 14He had already begun to deliver “The Problems of Philosophy”, twenty lectures given to the British Institute for Philosophical Studies, 7 October 1925 to 26 March 1926.

- 15“The Problems of Philosophy”, 4 October 1926 to 21 March 1927; “Mind and Matter”, 6 October 1926 to 16 March 1927.

- 16This first lecture tour of America covered the Atlantic seaboard and the mid-West. Organized by his American agent, William B. Feakins, it lasted from 22 March to 7 June. On the ship home he told Ottoline on 2 June that he had cleared £1,450 to invest. Other tours followed in 1927, 1929 and 1931.

- 17On Education, Especially in Early Childhood.

- 18Russell still held the lease to Russell Chambers and had a tenant living there.

- 19Russell’s lawyer, Crompton Llewelyn Davies wrote to Russell on 17 October 1934 that he found it in his Strong Box at the office but that he had never read it before: “on reading it now I am perplexed.”

- 20The house last sold in 2006 for £2,200,000.