China1

Upon his return from Russia, Russell received an invitation to lecture for a year in China. “I decided that I would accept if Dora would come with me, but not otherwise” (Auto 2: 110). Despite a tug of wills, she agreed. After leaving Bagley Wood in 1911, Russell had not lived with a woman until he left for China with Dora Black in the summer of 1920. He was still sharing a flat with Clifford Allen in Battersea. And although he continued to hold the lease for Russell Chambers he had not lived there since 1916. He maintained relationships with both Ottoline Morrell, his former lover and friend, and Constance (Colette) Malleson, his current lover, during this year away. From his flat in Battersea, he asked Ottoline to select books for him “especially history and biography” to read in China (document 001571).

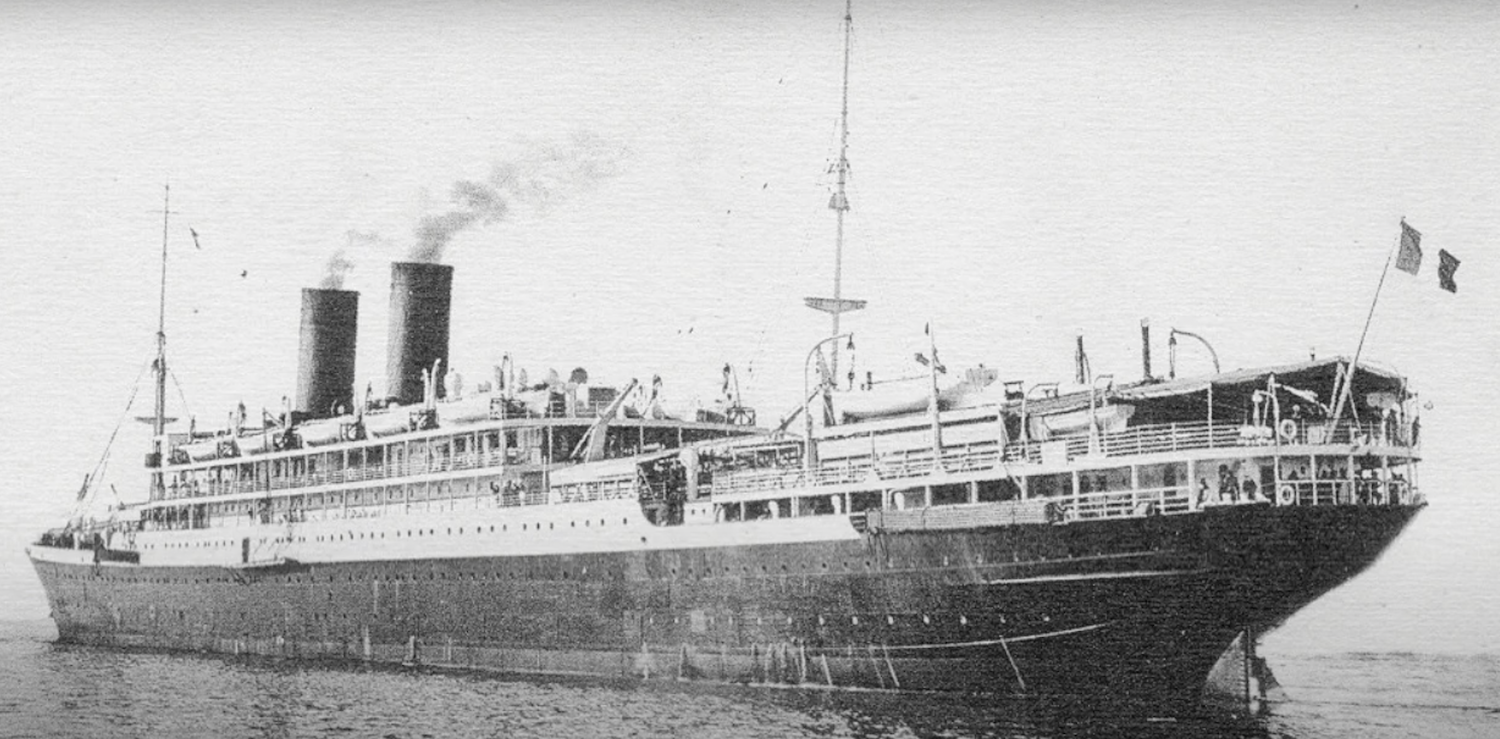

The couple were delayed in Paris because their ship had to be disinfected after a case of plague had been discovered (Auto 2: 124). They stayed briefly at the Hotel Louvois, then moved into a flat belonging to friends of Dora’s at 6 Rue Boissonade near the Luxembourg Gardens on 18 August. While there Russell finished his “book on Russia,2and decided, after much hesitation, that I would publish it” (Auto 2: 124). Russell described the flat to Colette as “close to Luxembourg [Gardens], looking out on a convent garden, very quiet and pretty—full of Chinese things, as it happens” (20 Aug.). They left the Paris flat on 4 September. Their ship, the Porthos,3sailed from Marseilles on 6 September.

“The voyage lasted five or six weeks” (Auto 2: 124). Their route took them across the Mediterranean and through the Suez Canal and the Red Sea. Russell listed all the ports of call for Colette: Port Said, 10 September; Djibouti, 14 September; Colombo, 20 September; Singapore, 25 September; Saigon, 28 September; Hong Kong, 3 October; Shanghai, 7 October; and she promised a letter would await him in every port. The list also noted arrival in Beijing on 14 October (document 200678). While they were parted, they planned to edit a book of their love letters with disguised identities. Some of these letters survive in the Archives.

Russell wrote to Ottoline from the Indian Ocean on 17 September thanking her for the books she had selected for him. He had already read two of them about China. Yesterday he had been in Djibouti in Africa. He saw “negroes diving for pennies and in the intervals singing Tipperary.” He wrote Ottoline a second letter while still at sea, this time between Hong Kong and Shanghai on 11 October. He told her that “The voyage has been so long that it grows difficult to conceive life away from the boat…. We made a number of friends on the boat…. The one I liked best was a Chinese Professor at Pekin, named Liang…. we were introduced by Mr. Liang as ‘Professor Russell and the very intellectual Miss Black’. This is apparently to be our official style.” Dora explained in her book that this introduction took place at a Chinese restaurant dinner hosted by Liang just outside Saigon (Tamarisk Tree, p. 113).

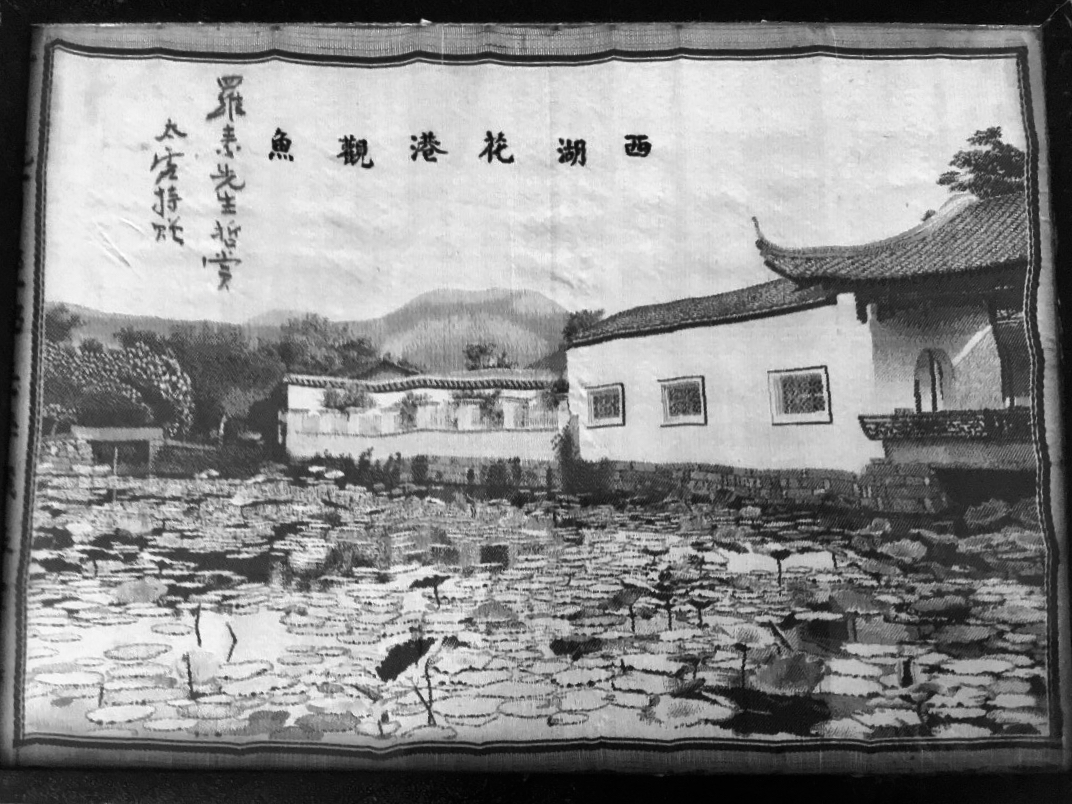

His first letter to Ottoline from China was written from Hangzhou on 18 October. By then he had been in China for six days. “I hope to get to Pekin in about a week but meantime I have to go a place [sic] a long way up the Yiangtse [Yangtse] where they are having an educational conference—in the province of Hu-Nan [Hunan]…. This place is wonderfully beautiful…. The country is even more humanized and ancient than Italy….” His second letter was written from the Yangtze on 28 October. He provided a description of Shanghai. It “is quite European, almost American; the names of streets, and notices and advertisements, are in English (as well as Chinese). The buildings are magnificent offices and banks; everything looks very opulent. But the side streets are still quite Chinese. It is a vast city, about the size of Glasgow” (Auto 2: 137). He ended this letter, which was published in The Nation (C21.03), with the news that he hoped to reach Beijing by 31 October.

Shanghai Welcome Group at “Chung Kuo Kung Hsueh” [Zhonguo Gongxue] high school

Close-up of the welcome group; “Fu T’ung” [Fu Tong] is standing beside Russell and Dora

In addition to his letters to Ottoline, Russell was of course writing to Colette. He wrote to her from the Mediterranean on 8 September and then from the Red Sea on 11 September, telling her: “The passengers are about a third French, a third English, and the rest odds and ends: Syrians, Chinese, Dutchmen, Danes, etc. None seem interesting except the Chinese. Professor Liang, the best of them, spends his time translating my Russian book into Chinese, so it may appear in China before it appears in England.” From the Indian Ocean he wrote on 18 September describing his cabin mate, “a Hong-Kong merchant, snores 10 hours every night, is proud of making love to European ladies—they seem to like him. I don’t know why.” On 24 September he wrote again from “off Ceylon.” Dora’s cabin mate was Mrs. Allen, “a nice fresh young thing, not yet twenty-one”. He mentioned a second cabin mate for himself: “a rosy Dane who sleeps … almost the whole 24 hours—whenever he is awake he argues about Einstein—his job is irrigation for the Siamese Government…. A great many people, including myself, sleep on deck,4because the cabins are insufferably hot, though it has been much less hot since we got out of the Red Sea…. The Peking Professor Liang is one of the nicest people on board—he has translated chunks of my book on Russia, and is publishing an article on me as soon as we arrive. He has got me much interested in Chinese problems.”5His next letter was written “between Singapore and Saigon” on 30 September. On 7 October he wrote again as he was nearing Hong Kong. The very next day he wrote from Hong Kong: “This is much the most beautiful scenery we have seen. The town is surrounded by very steep wooded hills, and the harbour is full of islands—it almost reminds one of the Lakes. It is not hot—there is wind and rain, which is delicious—especially after Saigon which was a nightmare. I don’t like what I have seen of the tropics.”

His first letter to her from China was written from Shanghai on 18 October: “Since I landed here I have been absolutely overwhelmed: the Chinese have given me such a welcome as I never imagined. They hail me as the second Confucius, and invite me to tell them exactly what they are to do with their country. It is a terrible responsibility.” His next letter to Colette was written on 25 October from the Yangtze river on a steamer. On 29 October he wrote to her from Hangzhou: “At last we are really on our way to Peking .… At Chengsha [Changsha], at a moment’s notice, I gave 4 lectures in 2 days.” Dora wrote that after Hangzhou we “were taken back to Shanghai and thence up to Nanking [Nanjing], where Russell lectured to the Science Society” (Tree, p. 115). In his Autobiography Russell wrote about the conference held in Changsha where he met John Dewey and his wife (2: 126).

Russell with the Nanjing Science Society

After six weeks of travel Beijing was finally reached. “Our first months in Peking were a time of absolute and complete happiness…. Our Chinese friends were delightful. The work was interesting, and Peking itself inconceivably beautiful” (Auto 2:127). Russell’s first letter to Colette from Beijing was written on 2 November 1920: “We are staying in a hotel for the present, looking for a house, but there are difficulties and we may stay where we are. I have not yet begun lecturing here. Peking is beautiful, with many wide spaces, trees, temples, gates and ancient walls. The weather is Indian summer, very delicious, crisp with bright sun.” This was the Continental Hotel. The hotel was on Morrison Street. Russell’s translator, Zhao Yuanren,6had met Russell in Shanghai and was staying with Russell and Dora there. (Buwei Chao, Autobiography, 1970, pp. 174-5). Morrison Street, a shopping street in the Dongcheng [East City] district, is now called Wanfujing. Russell wrote a letter from that address to Zhang Shenfu on 10 November. He was replying to a letter from Zhang, who became an expert on Russell, of 9 November published in “Between Russell and Confucius,” p. 120.

They decided to rent a Chinese home instead of living in a “modern-style flat” as many expats did. Dora found the house where she “spent the happiest months” of her entire life (Tree, p. 119). The address of the house was 2 Sui An Buo Hutung. It was located near the North Road of Tongdan in the Dongcheng [East City] District. “Sui An Buo” refers to an Earl in the Ming Dynasty. “Hutung” translates as an alley or laneway. Russell and Dora wrote the street address in different forms.

Dora described the home in great detail in her autobiography, The Tamarisk Tree. “Chinese houses are designed for a private life. The streets in Peking as I knew it then, were no more than narrow tracks between grey walls…. In our house … there was a first small courtyard, with one room whose wall backed on the street; on each side—East and West as the Chinese would say—were kitchen and servants’ quarters. Then came a screen beyond which was the second courtyard. A separate screen stood in front of the opening entrance to this court, and you entered round it, for it kept out the evil spirits, who can travel only in a straight line. East and West in this second court were the two rooms in which Mr Chao [Zhao] came to live; the main part of the house faced south with three steps and a narrow veranda which we embellished with pots of flowers. Here were four rooms, one of fair size, the others small. The bedroom was almost entirely filled by a double bed, thus we had a dressing room; then there was the study where Bertie worked, and the very small room off that which was mine. The door, by which you entered straight into the main room, had some glass panels…. The veranda, of course had the typical round pillars, and the roofs were of the lovely Chinese tiles in grey. We had a tiny annex in which was an earth closet that was cleared daily and kept scrupulously clean” (Tree, pp. 119–120).

“Everything had to be acquired: linen, cutlery, china, kitchen equipment, as well as furnishings. I did the dull buying in the mornings while Bertie was working, and then in the afternoon we would go to the junk-shops outside the city gate and bargain on our fingers for Chinese chairs and tables…. We bought an old Chinese sofa, of very dark brown redwood … the kind of sofa used for smoking opium…” (Tree, p. 120).

Russell wrote to both Ottoline and Colette about the house. To Ottoline on 17 November: “We inhabit it with my interpreter, a Mr. Chao [Zhao], who has lived 10 years in America, & hates all Chinese things. We have bought all Chinese furniture for our rooms, & he has bought all American things.... We have 3 rickshaw boys, one each, a cook, & a boy who acts as parlour-maid and housemaid. We have old wiggly Chinese bookshelves, heavy black Chinese chairs, a big divan of the sort they used to use for smoking opium, lovely square tables, all black—we get bright colour from curtains & rugs—the sun shines in & makes it hot, although it is ... cold by now here.” Zhao noted that it was necessary “to find an English-speaking servant-cook, as I was in no way obliged or qualified to do that sort of interpreting” (“With Russell in China”, p. 14). Zhao invited his future wife, Buwei, to dine. She remembered that she “had eaten beautiful foreign-style meals with him when he was staying in the same house with Bertrand Russell” (Buwei, 1970, p. 196).

Russell drew Ottoline a floor plan marking out the rooms around the courtyard. The kitchen next to Zhao’s bedroom on the east side of the house; the bedroom, Dora’s work room, the big sitting room and a small work room on the north side; Zhao’s sitting room, the cook’s room, and the “rickshaw boys’” room on the west side; and the dining room and the box room on the south side. A partition separated the kitchen, the “boys’ room” and the south wall from the rest of the house. This plan leaves out his study while Dora made no mention of the sitting room in her book.

Floor plan of his Chinese house, drawn by Russell

On 6 November he told Colette that he was “taking a Chinese house…. I have just come in from lecturing to well over 1000 people, the first of a course of lectures on popular philosophy. Also I shall give a less popular course on analysis of mind, & have a seminar in connection with it. And later on I shall lecture on Social questions.” In the same letter he expressed doubts about the editing and publication of their love letters. Later that month he wrote from his house which was situated “round a courtyard, only ground floor, very Chinese and delicious—I have filled it with old furniture and Chinese rugs and lovely things—it is not finished yet—it is great fun.” He added that he was “dreadfully busy as yet as the house got me behind …” (17 Nov. 1920).

In an email in 2014 from Zheng Weipeng, who studied at McMaster and then returned to China, I was told that the laneway on which the house was located had been demolished. Bernie Linsky went to visit the laneway in 2018 with Lianghua Zhou during the World Congress of Philosophy. In an email he told me that the block containing Russell’s house “was torn down to fit in an international hotel and replaced with the modern Hongxing Hutong.… But the road is still there.… Bertie could have walked to work at the red building on the other side of the Forbidden City where some of the Peking University buildings were then located…. I attach a photograph of the entrance to Suianbo 37, across the street from where Hongxing Hutong begins.” Linsky noted that one hundred years ago these courtyard houses had been the “homes of upper classes.” Now they are slums. At the end of the “little half block” is “the Jiangoumen Police station.… The big street Jinbao at the end is a high end shopping street” (8 May 2021).

Suianbo 37, photographed by Bernie Linksy in 2018

On 7 November Russell gave his first lecture on the Problems of Philosophy at the University to an audience of 1,500. Other lectures followed on the analysis of mind, idealism, causality, theory of relativity, and symbolic logic. Some lectures were held at “the Teachers’ College, which had a very large auditorium” (“With Russell”, p. 15).

Russell recollected the Chinese love of fireworks: “When I invited the most intellectual of my students to an evening party, they sent several days ahead extraordinarily elaborate feux d’artifice to be let off in my courtyard” (Papers 15: 307–8). There is a photograph of Russell in the courtyard in Luosu Yuekan, unfortunately of poor quality. The newly acquired Archives 4 has an excellent image of the same photograph which appears below. Luosu Yuekan was edited by Ch’u Shih-Ying [Qu Shiying]7and was published by the Commercial Press, who became and remained Russell’s publishers in China (Simpson, pp. 13, 20.) The Commercial Press also approached Zhao to publish a textbook “for the newly standardized National Language” and to make a “set of phonograph records … with the Columbia Phonograph Company at New York” to which Zhao agreed (Buwei, 1947, p. 201.)

Russell in the courtyard of his Chinese home

On 3 December Russell conveyed to Colette that doubt about his time in China had crept into his thoughts. “The Chinese are heartless, lazy and dishonest—they leave the famine relief almost entirely to Europeans, and their Government is utterly corrupt. Most of the students are stupid and timid. I don’t really feel that what I am doing here is worth doing. The Deweys, who have been here over a year, are utterly discouraged. There is ancient beauty, but it is dead. There is new intellectual life, but it is as yet very second-rate.”

Russell with John Dewey and Zhao in front of the “Justice Wins” archway

Only a few days later he reflected back to his time in Changsha during a lunar eclipse. “I dined at a banquet … given by the Governor of Hu-Nan [Hunan], in the very centre of China. When the eclipse began people beat gongs, in the old regulation style, as they did 4000 years ago; and they lit fires, to receive the moon by sympathetic magic. Meanwhile we feasted and drank Chinese wine. It was like the scene in the beginning of the Confucian history when the astronomers-royal get drunk during an eclipse” (7 Dec.).

On 13 December he wrote his friend and former flat-mate, Clifford Allen, that he and Dora “are very happy, though we have fits of home-sickness, but we are too busy to notice them much.” On the 15th of December he wrote to Colette: “I am doing 3 courses of lectures, as well as odd papers and newspaper articles. The result is I have very little spare time, except for an afternoon walk, either to buy furniture for the house, or along the City Walls, which go all round Peking (14 miles), with lovely views of the Western Hills. The weather is bright and frosty, very delicious and healthy. I am full of beans. But China is depressing; it is decaying and rotten, like the late Roman Empire.”

On the 17th he wrote Ottoline: “Last night for the first time we had visitors to dinner in our house.” During the dinner there was an earthquake. “I never was in an earthquake before—it was slight, and at first we each thought we were taken suddenly ill—it felt like sea-sickness. Then we saw the lights swaying about and we realized what had happened.” He enclosed photographs of his house. “In one you will see the delicious books you sent me. They are above my desk and to the right of it.” The photographs are at the University of Texas in Austin and cannot be reproduced without a fee.8

Russell at his desk

He wrote to Colette both on Christmas eve and again on Christmas Day. In the first letter he reflected that “It is strange spending one’s Xmas in this remote place….” In the second letter he announced: “At last I have made up my mind what I feel about this place—it is not cheerful.” He went on to outline his plans from 1 May onward when he and Dora would leave Beijing. Unfortunately, these plans never came to fruition because he was to fall severely ill. These two letters were followed by a “first Chinese letter” which expanded on his “not cheerful” remark. This letter may have been a substitute for the abandoned love letters project. Although it mainly contains a big-picture view of China, it begins with the front door of his house. It “opens into a small street: as one walks along the street, one sees only one continuous wall with an occasional door, because the houses are hidden. Ten minutes walk from my house are the City Walls…. They are high and broad, and the best place for an afternoon walk, because one sees the whole of Peking and the Western Hills beyond” (document .200722).

Russell standing on the Tartar wall

On New Year’s Day, he told Colette: “The wind is howling outside and it is bitterly cold after a fall of snow, but by dint of stoves we keep warm indoors—it is too cold to go out. Last night for New Year’s Eve they put Chinese lanterns along all the main streets—it was lovely, with the snow falling.” On 6 January 1921 he praised “the ‘Japan Chronicle’ … very witty, and having exactly one’s own views. I don’t think I shall write on China—it is a complex country, with an old civilization, very hard to follow.9In many ways I prefer the Chinese to Europeans—they are less fierce—their faults only injure China, not other nations. I have a busy life … for instance today I lecture on Religion. I like the students, though they don’t work hard and have not much brains. They are friendly and enthusiastic, and very open-minded…. I get £200 a month from the Chinese, and £100 a month from the Japs for articles10—so I am very well off. I try to save, but men come round with lovely Chinese things, and the money goes. Also of course furnishing cost a good deal…. There is less government in China than there ever was in Europe—it is delightful. All the gloomy things I wrote you the other day are true, but they are only one side of the picture.”

On 13 January he wrote his sister-in-law Elizabeth about a typical day: “in the afternoons we walk on the wall, built about 800 years ago, where one sees the whole City & the Western Hills. In the evening if we don’t have to lecture we drink a mystic Chinese wine presented to me by an old Taoist, who also gave me some mandragora, then we dress up in Chinese robes & read fantastic stories of the Great Mogul or some other queer personage.” The next day he wrote to Colette: “If it were not for the ties of affection, I could live here happily for the rest of my days—the Chinese are good-natured, full of laughter and extraordinarily kind to Dora and me. I have a seminar where I meet the better students, and it is great fun. They are … sceptical and intelligent, but lazy.” In The Problem of China11he remembered “The discussions which I used to have in my seminar … could not have been surpassed anywhere for keenness, candour, and fearlessness” (p. 222).

On 18 January he alerted J.M. Keynes that “An emissary from here is coming to invite you to take my place in the next academic year.… I have a very good time here.… They pay me £1,000 a year plus travelling expenses.… The Far East is immensely interesting & begins to seem to me the centre of the World…. I lecture on Einstein, Behaviourism, Bolshevism, etc…. You had better come.” On the same day he wrote to Colette, reminding her that he loved her.

On 31 January he told her that “The Chinese feasts have diminished, and one has time for work…. Some of the students have formed a seminar, which they call ‘Society for the Study of Russell’s Philosophy’—we gave them a party 2 nights ago, with Chinese lanterns all round the courtyard, and brasiers burning in the middle—about 30 came, young men and girls, all very jolly, and very nice people…. When we have time, we go to the Temple of Heaven, which is most exquisite—great courts surrounded by woods, leading up to a great circular temple with wonderful blue tiles on the roof—everything with the most perfect proportions, and an atmosphere of peace that makes one talk in a low voice so as not to disturb it. I go on being very happy.”

Russell and Dora with the Society for the Study of Russell’s Philosophy; to Russell’s right is “Fu Ling-yu” [Fu Lingyu]

He sent a belated letter to Wittgenstein on 11th February; he had been meaning to write to him since September. His students “are not advanced enough for mathematical logic. I lecture to them on Psychology, Philosophy, Politics and Einstein…. Best love, my dear Ludwig—I shall hope to see you again, perhaps next year” (McGuinness, p. 115).

On 16 February he again wrote to Elizabeth: “My students here are charming people, full of fun—we have parties for them with fireworks in the courtyard, and dancing and singing and blindman’s bluff—young men and girl-students. In ordinary Chinese life a woman sees no men except relations, but we ignore that, and so earn the gratitude of the young. The students are all Bolshies, and think me an amiable old fogey, and hopelessly behind the times. We have a very happy existence, reading, writing, and talking endlessly.” On the same day he wrote to Colette: “I have booked my passage home, sailing from Yokohama for Vancouver on August 27. I am homesick for green lanes and soft air and rain—it has only rained once since I came to ...” Beijing.

On 21 February he wrote to Ottoline: “Since we have been in Peking we have settled down and lived a quiet life, getting a lot of work done, and seeing the sights slowly.” That day they had been to a Llama Temple. “We have been reading aloud one of the books you found for me, Huc’s travels in Mongolia and Tibet—a perfectly delightful book.” 12He has had a falling out with John Dewey. “In 1914, I liked Dewey better than any other academic American; now I can’t stand him.” The Deweys are “American imperialists, hating England … and unwilling to face any unpleasant facts.” He did not write to Ottoline again until April when he was in the German hospital recuperating from a serious case of pneumonia.

On 5 March he wrote to Colette: “Life here goes on uneventfully. Last week-end some Chinese friends took us out to the Western Hills and we had long walks over stony mountains inhabited by only a few sheep and shepherds…. Next week-end we go to the Great Wall.” This was his last letter to her before he fell ill. In his Autobiography he put his illness down to Beijing’s cold weather and catching bronchitis to which he “paid no attention.” He was two hours by automobile away from Beijing when he began to feel very ill (Auto 2: 130). In her book, Dora wrote that they were visiting the Western Hills with friends: “we both went to swim together in the hot spring. When we came out, in our room Bertie began to shiver violently…. He had double pneumonia” (Tree, p. 135). Dora described the difficulty of getting into Beijing because the gates to the city were locked; Zhao came to help them and they got Russell to the German hospital. She outlined the desperate state he was in: “… I sat hour after hour with my finger on Bertie’s pulse, giving him sips of champagne and spoonfuls of … cream” supplied by Russian Bolshevik friends (Tree, p. 140). Eventually she was able to bring Russell back to their home: “we installed him on the soft blue cushions of the big divan…. He had to remain quietly in bed because … he had some poisoning in one leg…” (Tree, p. 141).

Zhao provided a third account of how Russell’s illness began: “he was a perfect English gentleman in manners down to the last detail in dress, a habit which almost cost him his life. On March 14, I went with him to Paoting [Baoding], about 100 miles south of Peking, where he lectured … on the subject of education. It was still wintry and windy and he lectured as usual without an overcoat while I shivered beside him even with my overcoat on.” Zhao went on to write that three days later Russell fell ill in Beijing (“With Russell”, p. 16).

Russell and Zhao

While still in the hospital Russell wrote to Colette on 27 April telling her that it was the first letter he had written with his own hand. “My illness was a strange experience…. I had 3 weeks’ delirium, which I have almost totally forgotten.” The following day he wrote to Ottoline, with more details on his delirium. “I also had music—unreal and mystic—always in my head.”

On 7 May he wrote to Colette. He hoped to leave the hospital soon and was longing to get home to England. By the 16th of May he was back at his house. “From my bed I see into the courtyard, which is full of roses and blossoming lemons.” On 25 May he wrote: “I am very tired of bed, and not being able to work—I haven’t yet the strength for work, and I suppose I shan’t have till I get up…. The weather is delicious—warm with occasional showers. The dryness of winter nearly drove me mad….” He wrote to Ottoline on 11 May: “Out of my [hospital] window I see great acacia trees in blossom, and think how dreadful it would have been to never seen the spring again…. I have read an obituary notice of myself. In Japan I was reported dead….”13

He wrote to Clifford Allen on 2 June, informing him that Dora was pregnant: “You can imagine how glad we both are…. I lie in bed and read all day long…. My work here, of course, was stopped dead by my illness, which I regret very much as I was just getting into real touch with the students….” On 14 June he wrote to Colette, telling her he got out of bed about a week ago. He broke the news that Dora was pregnant. On 26 June he told her that “Miss Power, a Girton don,14has turned up and undertaken to look after us as far as Vancouver.” Both his leg and heart were weak. He also wrote to Ottoline during June. On the 17th he told her: “Today I put proper clothes on—it is 3 months since I had worn anything but pyjamas…. It is annoying to have seen so little of China but it can’t be helped.”

The year that Russell had spent in China was very productive. He published numerous articles in Chinese and Japanese newspapers and periodicals. Upon his return he wrote for the Manchester Guardian and the Atlantic Monthly (C21.25, C21.26). The latter article appeared in The Problem of China which was published in September 1922 as did other articles, including one in Time and Tide. His lectures have been listed by Lianghua Zhou. He also maintained his interest in Russia, commenting on events in letters, and continuing to write on the subject.

The last letter that Russell wrote from China was on 8 July to Colette. He was at the “Grand Hôtel de Pékin.” “My house was sold up yesterday,15and the furniture put up to auction. I am in bed from the combined fatigue of that and packing and a farewell lecture16 and a farewell Chinese feast, but it is only a slight digestive upset. We go from Tientsin [Tianjin] to Kobe by boat, spend 13 days in Japan, and then come straight home, with perhaps 2 days in the Canadian Rockies.” At the dinner Russell was given a farewell cup. The text has been translated as: “Drink with boundless music Greatest Mr. Russell a gift July of the 10th year of Republic (1921) Presented by Education Minister Ma Lin-yi” (Simpson, p. 150).

Farewell Cup, Side A and B

Zhao and his new wife, Buwei, said goodbye to the Deweys in the morning and Russell and Dora in the afternoon of 11 July. Zhao noted that this date, taken from his diary, conflicted with the date of 10 July which Russell gave in his Autobiography 2, p. 132 (“With Russell”, p. 17). Zhao and Buwei had married on 1 June. Zhao left his rooms at Russell’s home, Buwei left her former home and they lived together at 49 Hsiao Yapao Hutung (Buwei, 1947, p. 198). “We had a small roof garden over our house, on which we had ‘mad tea parties’ and club meetings” (Buwei, 1947, p. 202). The illustration below shows Zhao and his wife on either side of Russell; across the table are Dora and E.S. Bennett of the British Legation. The photograph was taken after Russell had recovered from pneumonia and before he left Beijing.

“A roof garden party in Peiping [Beijing]”

Russell was leaving on a positive note; he concluded The Problem of China with the affirmation: “… China deserves a foremost place in the esteem of every lover of mankind” (p. 322).

Eileen Power was with them on the return voyage. Dora seemed to indicate that that they had met her before Russell became ill (Tree, p. 131). In his Autobiography Russell explained that: “Before I became ill I had undertaken to do a lecture tour in Japan…. I had to cut this down to one lecture, and visits to various people” (2: 133). The whole experience was very unpleasant, mainly because of journalists that pursued them relentlessly.

Power wrote to a friend of hers, Margery Spring Rice, on 31 July on board ship after departing Japan. “I am now leaving Japan after the most hectic fortnight you can imagine. In Peking I fell in with Bertrand Russell & Dora Black.” She explained that Russell had been ill. “He is still rather a crock & Dora is expecting an infant anon, so they asked me to travel with them from Peking to Canada, chiefly because the C.P.R. [Canadian Pacific Railway] is so prudish that it won’t let them share a cabin, & B. wanted someone to keep an eye on Dora. So off we started all very gay, meaning to have a nice quiet incog. sort of fortnight in Japan. But we reckoned without the Japanese reporters. B. has an enormous vogue there just now & altho’ he had given out that having been ill he was giving no interviews & was travelling as a private person, it hadn’t the least effect.… We lived in a perpetual fire of flash light photographs, cameras, cinemas [cameras] & what not. [On the trains they] sat close to us with their ears wagging & tried to overhear our conversation. All our doings were chronicled.… What role they thought that I played … I do not know, but I suspected that it was the familiar oriental one of Second Concubine! Dora & I made a limerick about it.… You can’t image how unfavourably they compare with the Chinese.”

Russell and Dora left Yokohama, Japan on the Canadian Pacific steamship the Empress of Asia17bound for Canada, still accompanied by Eileen Power. Maxine Berg wrote that Power “enjoyed Russell’s wit, and ‘discussion of politics, books & the position of women raged furiously’” (Woman in History, p. 104). Dora was noticeably pregnant and as a result “almost nobody would speak to us, though everybody was anxious to photograph us. The only people willing to speak to us were Mischa Elman, the violinist, and his party” (Auto 2: 135). To Colette Russell wrote: “We were 13 days in Japan—the scenery is exquisite, as lovely as I have seen, and the temples are very fine, but the people are odious. I have decided that on the balance I like the Chinese very much, and could live among them happily …” (6 Aug. 1921).

Russell and Mischa Elman on the Empress of Asia

They travelled by train from Vancouver across Canada, arriving in Montreal where they embarked for Liverpool on 17 August on board the Canadian Pacific steamer Metagma.18 They arrived back in England on 23 August. Both Russell and Dora barely mention this part of the trip in their books. There are no extant letters to Ottoline or Colette.

On 26 August he wrote to Ottoline from the flat in Battersea that he had shared with Allen. He and Dora were planning on staying there “for about a week and then probably go to the country.” The next chapter of his life was beginning. He had been away from England for a year and wouldn’t be out of the country again for such a long period until World War II.

Russell’s time in China has provided rich material for academics. The field continues to be mined with new work appearing regularly.19 John Paisley has recently written that Russell’s visit was “important because the matters he wrote about … still resonate deeply in China as if part of living memory” (“Bertrand Russell and China”, p. 210). Every year I worked in the Russell Archives I welcomed visitors from China who were thrilled to be there. They felt a real connection to Russell.

© Sheila Turcon, 2021

Acknowledgement

The Mistress and Fellows, Girton College, Cambridge, for the letter from Eileen Power to Margery Spring Rice.

Sources

Maxine Berg, A Woman in History: Eileen Power, 1889–1940. Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Buwei Yang Chao, Autobiography of a Chinese Woman Put into English by her Husband. New York: The John Day Company, an Asia Press Book, 1947; re-published by Greenwood, 1970 with pagination changes.

Yuen Ren Chao, “With Bertrand Russell in China”, Russell, o.s. no. 7 (Autumn 1972): 14–17.

B.F. McGuinness and G.H. von Wright, “Unpublished Correspondence between Russell and Wittgenstein”, Russell, n.s. 11, no. 2 (Winter 1990–91): 101–24.

John Paisley, “Bertrand Russell and China During and After His Visit in 1920”. Harvard M.A. thesis, 2020.

Richard A. Rempel and Beryl Haslam, eds. Uncertain Paths to Freedom: Russia and China, 1919–22, Vol. 15 of The Collected Papers of Bertrand Russell. London: Routledge, 2000.

Bertrand Russell, The Autobiography of Bertrand Russell 1914–1944. Vol 2. London: Allen & Unwin, 1968.

Bertrand Russell, The Problem of China. London: Allen & Unwin, 1922.

Dora Russell, The Tamarisk Tree: My Quest for Liberty and Love. New York: Putnam, 1975.

Vera Schwarcz, “Between Russell and Confucius: China’s Russell Expert, Zhang Shenfu (Chang Sung-nian)”, Russell, n.s. 11, no. 2 (Winter 1991–92): 117–46.

Tony Simpson, “Russell and China”, Spokesman, 130 (Nov. 2015): 13–23.

Tony Simpson, “Russell’s Chinese Farewell Cup”, Russell, n.s. 40, no. 2 (Winter): 150.

Lianghua Zhou, “A Critical Bibliography of Russell’s Addresses and Lectures in China”, Russell, n.s. 36, no. 2 (Winter 2016–17): 144–162.

Emails: correspondence with Zheng Weiping and Bernard (Bernie) Linsky.

Archival correspondence: Ottoline Morrell, Constance Malleson, Elizabeth Russell, J.M. Keynes, Clifford Allen, Zhang Shenfu.

Internet Sources

S.S. Porthos website: This website contains images of the ship, including interiors, which are of too poor quality to reproduce here.

S.S. Porthos website: Additional images of the ship are found here.

S.S. Porthos video, 5 minutes of still images with text in Portuguese. Empress of Asia website

- 1Names are presented in pinyin in my text; for quotations the original word is followed in square brackets by the pinyin equivalent. Peking (Pekin) is now widely known as Beijing so I have not felt it necessary to insert it into quotations.

- 2The Practice and Theory of Bolshevism.

- 3This French ocean liner was built in 1914 and sunk off Casablanca in 1942. It could carry 1,300 passengers in three classes. Its top speed was 17 knots (31.5 kilometers) an hour.

- 4They slept under a canopy with mosquito netting, Tree, p. 112.

- 5The title of the book Russell published after his year in China, The Problem of China, expanded on this idea.

- 6Yuen Ren Chao [Zhao Yuanren], 1892–1982, an eminent linguist. He kept in touch with Russell, last visiting him at Plas Penrhyn in Wales in 1968.

- 7There are two issues of this very rare journal held by the Russell Archives.

- 8The photographs are images of his study, the exterior of his house, the Summer Palace, the Manchu Palace, and the Western Hills. Also included in this grouping is the same image of Russell at his desk that he sent to Colette.

- 9In fact he did write a book, The Problem of China.

- 10He wrote many articles for the Japanese Kaizo.

- 11The book does not contain many personal memories of his time in China.

- 12Evariste Régis Huc, Souvenirs d’un voyage dans la Tartarie, le Thibet pendant les années 1844, 1845 et 1846. Paris: Gaumefrères, 1847. Russ Lib 926-7.

- 13See Kirk Willis, “Russell and His Obituaries,” Russell 26, no. 1 (Summer 2006): 5–54.

- 14Eileen Power, 1889–1940, was abroad on a Kahn Travelling Fellowship. While away she had accepted a position as lecturer with the London School of Economics and was returning to England to take up the post.

- 15This implies that Russell had purchased rather than rented.

- 16“China’s Road to Freedom”, given at the Board of Education; Papers 15: 50.

- 17The ship was launched in June 1913. It was converted to a troop carrier during World War II and attacked and sunk near Singapore in February 1942. There were 1,000 passengers on board during Russell’s sailing. Prominent passengers, including Russell, are noted on the ship’s website; see Arrivals, 8 August 1921, Vancouver.

- 18The ship was launched in 1914 and scrapped in 1934.

- 19A recent example is Jan Vrhovski and Jana S. Rošker, eds., Bertrand Russell’s Visit to China. Ljubljana U.P., 2021.